The centrality of relationships

We know how much relationships matter in terms of our health, happiness, resilience, identity, and personal development. This is confirmed across the human services literature which consistently demonstrates the value from investing time and effort in building positive and meaningful connections and relationships, repairing fractured or ruptured relationships, and helping people to move from ‘relational poverty’ to ‘relational wealth’. We are fundamentally relational beings, hence the oft-heard expression that “it’s all about relationships”.

To help conceptualise relationships in the broadest sense and think about all the relationships surrounding a person, the concept of the ‘relational universe’ highlights the importance of considering each individual relationship of significance for that person – whether for better or for worse – and the entirety of the relational interconnections in their life.

Across the following sections, we highlight the centrality of relationships within current models and frameworks and how these influence probation and youth justice services.

The centrality of relationships within current models and frameworks

There are a range of models and frameworks which have relevance to probation and youth justice services and which have (to differing extents) influenced developments. The importance of relationships – at differing levels – is often highlighted, as can be seen from the following examples.

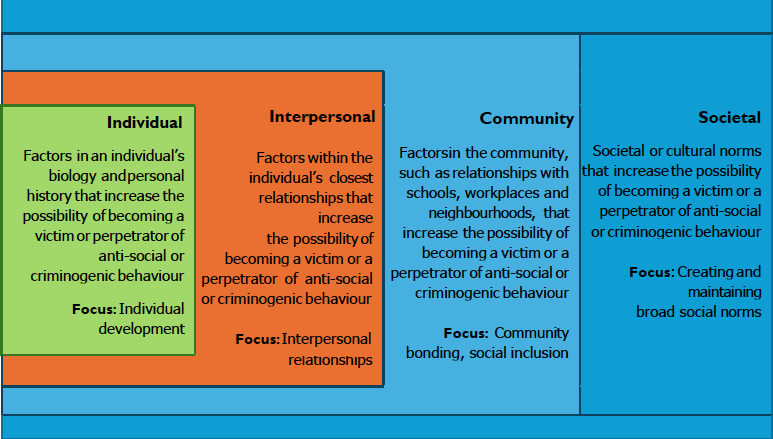

Social-ecological framework: ecological systems theory highlights the importance of understanding all individuals in the context of their lives. A social-ecological framework has thus been promoted, which sees people in terms of their relationships with their immediate environments of family, friends, school and neighbourhood, and the wider sociocultural, political-economic context. As set out in the visual below, a whole systems approach is required which recognises the need for a range of different activities at the individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels. The focus is upon discovering what is important to an individual – building trust slowly so they are willing to engage – and then opening up access to opportunities, helping to (re)build social relationships, supporting positive connections with agencies and community resources, generating pro-social activities, and fostering people’s interests and strengths.

Social-ecological framework – the four levels

Human Learning Systems: this approach also highlights the importance of supporting healthy systems. The premise is that outcomes cannot be ‘delivered’ by public services, but are created by whole systems, encompassing all the relationships and factors in someone’s life. Positive outcomes are generated within healthy systems when all the people involved are able to collaborate and learn together. The approach is summarised in the following video, produced by the Centre for Public Impact.

Disclaimer: an external platform has been used to host this video. Recommendations for further viewing may appear at the end of the video and are beyond our control.

Social pedagogy: the Charter for Social Pedagogy in the UK and Ireland states that ‘we believe in relationship-centred practice that recognises and engages with the whole person and the networks, systems and communities that impact upon their lives’. Social pedagogy is a holistic and relationship-centred way of working, nurturing learning, wellbeing and connection both at an individual and community level through empowering and supportive relationships. The extent, quality and supportive character of relationships is the cornerstone of planning and practice which is individualised and context specific, helping people to fulfil their potential.

Restorative justice (RJ) works through the power of relationships, and seeks to repair harm, restore and strengthen individual relationships, and enhance access to appropriate resources. More broadly, it has been argued that integrating a restorative culture can help to build positive relationships with and among colleagues, clients and the wider community, supporting collaborative dialogue and decision-making, promoting multi-agency work, and healing any divisions.

Adolescent safeguarding: the effectiveness of adolescent safeguarding systems extends beyond the scope of any one service, organisation, or professional sector, thus requiring effective relationships and collaborations within and between multi-agency and multi-disciplinary partnerships. It has been argued that at its best adolescent safeguarding involves the adoption of a relational approach at every level of the local system. There must be continual and active investment in these relationships, and it should not be assumed that it will be an automatic by-product from the legal mandation of safeguarding as ‘everyone’s responsibility’.

Systemic Resilience: the concept of Systemic Resilience brings together systemic thinking and resilience theory. Moving beyond an individualised view that locates resilience as a requirement of the child, it recognises the importance of strengthening the protective factors around the child including within their family, their community, and in the services that are available (also described as an ecological resilience framework). The implications for youth justice of adopting a systemic resilience led approach include:

- developing services that place a meaningful relationship with the child and their family at the heart of service provision

- developing the capacity of parents (or carers) to effectively parent the child

- promoting positive relationships for the child in their families, schools and communities

- enabling engagement with community resources.

A relationship-centred approach in probation and youth justice

The clear message for probation and youth justice is that relationships should be central and take precedence over processes – approaches should be relational rather than transactional. A relationship-centred approach should pay attention to the importance of reducing ‘relational distancing’ and to building and maintaining positive relationships and connections at the community, system, organisational, and practitioner levels – these levels and the relationships within them do not exist in isolation from each other but are interrelated and exert influence upon each other.

Nurturing, valuing and prioritising relationships at all the levels (and addressing any barriers to the building of these relationships) is beneficial for all – communities can become stronger and more resilient, organisations and systems become more successful and efficient, and individual people become happier, more resilient, and better supported in their positive development. Crucially, this is not simply about valuing good relationships but putting relationships first – paying attention to the impact we have upon others – with all interactions and human encounters seeking to positively strengthen relationships and connections.

Key references

Johns, D.F., Williams, K. and Haines, K. (2017). ‘Ecological Youth Justice: Understanding the Social Ecology of Young People’s Prolific Offending’, Youth Justice, 17(1), pp. 3-21.

Lowe, T., Padmanabhan, C., McCart, D., McNeill, K., Brogan, A. and Smith, M. (2022). Human Learning Systems: A practical guide for the curious.

Michel, C. and Billingham, L. (2024). Creating conducive conditions for relational practice to flourish in our adolescent safeguarding systems.

Squires, B. (2022). Social pedagogy and relationship-based social work with adults: Social pedagogy toolkit.

Tidmarsh, M. and Marder, I. (2022). ‘Beyond Marketisation: Towards a Relational Future of Professionalism in Probation After Transforming Rehabilitation’, British Journal of Community Justice, 17(2), pp. 22-45.

Last updated: 31 January 2025