Sustained integration and inclusion is best supported through wider collaborative social relationships and strong, functioning connections across local communities, creating broader safety nets of support and promoting genuine acceptance and belonging. For example, the aim of an Inclusive Recovery City (IRC) – which has been introduced in locations across the UK and the rest of Europe – is to build community resources, assets and connections to improve the wellbeing of people seeking recovery but also other marginalised and excluded groups such as people desisting from crime, those struggling to overcome mental health problems, or those marginalised on the basis of some other personal characteristic. It is an approach that helps to ensure that recovery and desistance are not seen simply as isolated and individual events but as collective efforts that benefit everyone.

Bonding, bridging and linking social capital

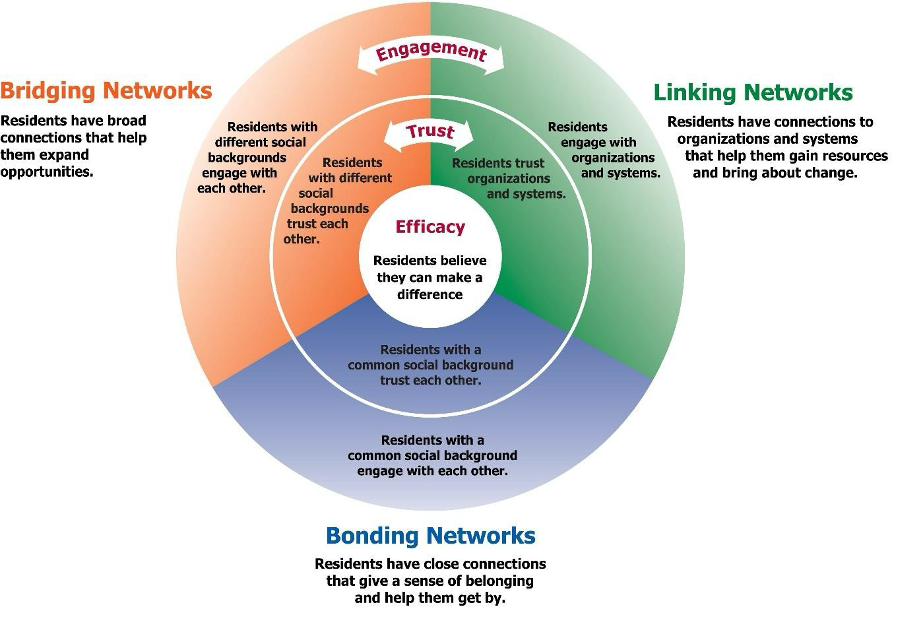

The team ‘social capital’ was used by Pierre Bourdieu (1986) to describe relationships, social connections and networks as assets that can either enhance or constrain an individual in the realisation of their immediate goals and in terms of their longer-term life chances. The task for probation and youth justice is to maximise the opportunities for social capital through operating as ‘network promotors’ and building close partnerships with local communities, accessing the social and relational networks and the resources which can support longer-term positive development that goes way beyond any specific intervention. Three forms of social capital have been identified:

- bonding social capital refers to intimate ‘horizontal’ ties, i.e. between similar individuals within the same family, social group or local community. These provide a sense of belonging and solidarity

- bridging social capital refers to the ties between different social groupings within a community, which enable access into more vertical social network resources and provide opportunities for cross group reciprocity

- linking social capital describes connections made through the sharing of social norms such as respect and trust. These interact across more formal, civic or decision-making contexts which involve gaining access to institutionalised authority.

Community-based mentors and relational navigators

Community-based mentors can function as positive role models, helping mentees to: openly discuss issues, concerns and dilemmas; clarify personal/professional goals; discover new directions; develop longer lasting support networks; and build confidence in terms of their strengths. It is a relationship-based approach; whilst each mentoring relationship is unique, it is based on the idea that our behaviour is influenced by those whom we have close contact with. The following three person-centred ‘core conditions’ have been highlighted as important: (i) caring; (ii) listening; and (iii) encouraging small steps.

There is evidence of positive impacts with differing groups. For example, mentoring has shown promise for women, particularly to help address social capital deficits and provide non-judgemental advice on practical matters. There is also evidence that mentoring can improve a range of measures for children, such as attitudinal/motivational, social/interpersonal, psychological/emotional outcomes, conduct problems, academic/school outcomes, and wellbeing. These effects can be more potent where the mentor is part of the child’s regular social network.

Potential components of mentoring

Akin to mentoring, the focus of ‘relational navigators’ is upon helping people with problem solving, and then providing referrals and coordinating support. The relational navigator seeks to build meaningful relationships of trust, care and compassion, within a pedagogical framework of guiding, facilitating and creating the conditions for transformative learning and development. Active listening is once again a key component, which involves attending to the other, reflection, and probing activities.

Key references

Fox, A. and Fox, C. (2024). The Motivational State: A strengths-based approach to improving public sector productivity. London: Demos.

Last updated: 31 January 2025