The foundation and bedrock of successful probation and youth justice work can be seen as the establishment of positive, supportive, respectful and trusting relationships between individual practitioners and people on probation/children. The research literature – which also uses the language of ‘working alliances’ – consistently highlights the importance of these relationships in terms of both engagement and enhancing other interventions, ultimately improving individual’s life chances.

Notably, in the Council of Europe Probation Rules, the first basic principle states that:

The benefits of relationship-centred practice

The research evidence indicates that relationship-centred practice has benefits both for people on probation/children and for practitioners.

Benefits for people on probation/children: there is evidence to suggest that positive relationships are more influential than any single specific method, technique or intervention, with individuals more engaged and influenced to change by those whose advice they respect and whose support they value. Individuals have reported how feelings of personal loyalty towards their supervising officer can make them more accountable for their actions, and more willing to share their views and experiences, communicate their needs, and utilise available forms of help. When an individual feels respected, valued, and empowered and when they perceive their practitioner as reasonable, knowledgeable, and empathetic, the relationship can create self-belief and hope and become the vehicle for learning and positive change. There is also some evidence that relational approaches may be therapeutic in themselves, boosting resilience and helping to repair some of the vulnerabilities caused by earlier developmental trauma. It has been highlighted that a humanised service which operates with a trauma and adversity lens must prioritise connection, belonging and relationships at the heart of the approach.

Benefits for practitioners: practitioners have reported increased job satisfaction when they are able to adopt relational approaches and build more meaningful and authentic relationships between themselves and those they supervise, supporting rehabilitation and reintegration. For many, relationship-centred practice enables them to fulfil the relational roles they originally envisaged when initially joining the service, which also means that they are less likely to leave.

The building of meaningful relationships as the primary goal: relationship-centred practice can unlock potential and meet individual needs by positioning meaningful and effective relationships as the first order goal, both as an end in itself and the means by which the other benefits set out above will be achieved. Notably, in setting out care ethics for probation, Dominey and Canton (2022) state as follows:

Key components of relationship-centred practice

Building and maintaining positive relationships can take time and hard work – there is no ‘magic bullet’ for impactful relational working – and it is clear that a wide range of practitioner skills are required. Helpfully, some underpinning principles have been set out for effective relationship-centred practice which can be applied across sectors. Building a relationship that is based on trust, respect and positive regard for the person is seen as the starting point; if a practitioner can connect, have meaningful conversations, and build an authentic relationship which is warm, hopeful and genuine, then they can create the conditions that enable positive change.

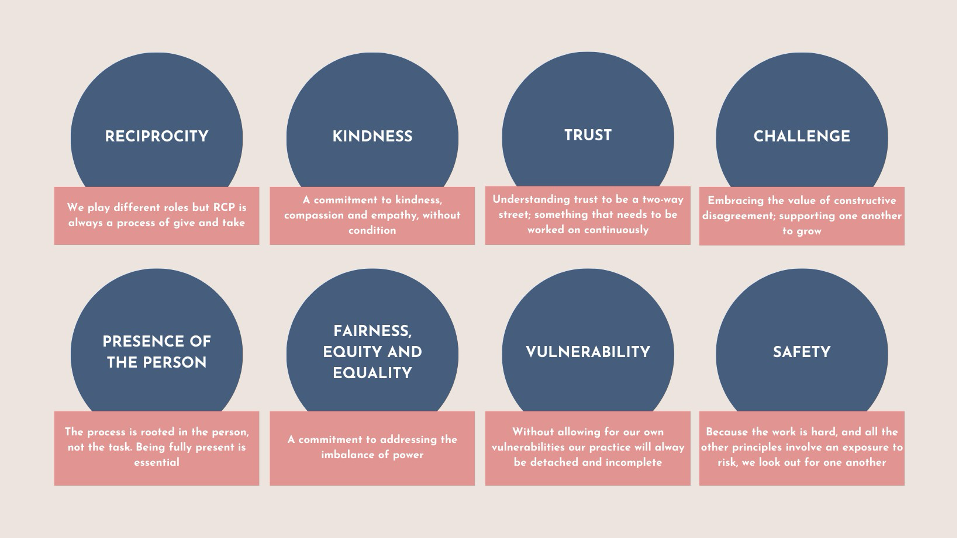

Underpinning principles for relationship-centred practice (Relationships Project, 2024)

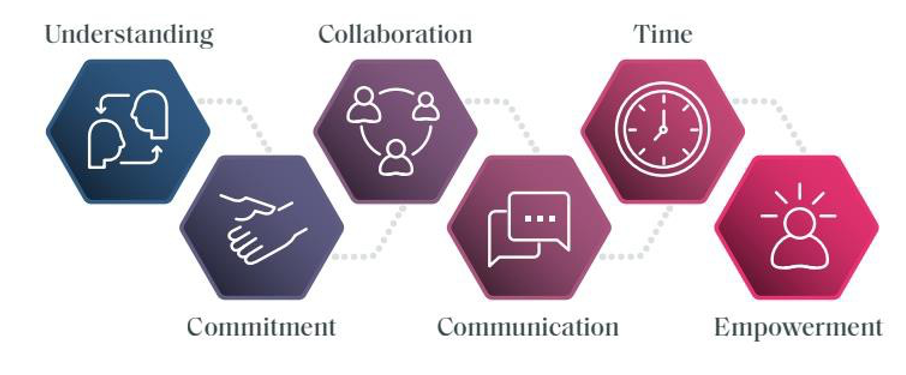

A literature review which looked at the role of effective relationships across public services identified the six key relational elements set out in the visual below. The review also highlighted the need for individuals to have trust and confidence in each other, and that where the role of the practitioner is to support the individual to change ways of thinking or behaving, the ability to confront and challenge without damaging the relationship is crucial.

Within the health and care sectors, the concept of ‘relational security’ recognises the need to go beyond having ‘a good relationship’ with an individual. Safe and effective relationships between practitioners and individuals must be professional, boundaried, therapeutic and purposeful.

Six elements underpinning effective relationships (Bell and Smerdon, 2011)

In psychotherapy, the ‘therapeutic alliance’ is viewed as key to change. According to the Working Alliance Inventory, a therapeutic alliance entails:

- trust: how comfortable the client feels, and whether they are confident about the therapists’ ability to help them

- mutual respect and collaboration: whether both parties feel understood, respected, and agree about how therapy will improve the client’s situation

- the client’s perception: that the therapist is genuinely concerned for their welfare, appreciates them, and is honest about how they feel even when the client says or does something wrong.

The research literature further highlights the importance of practitioners working alongside individuals, ensuring that whenever possible work is done ‘with’ and not ‘to’ them, increasing the likelihood that they will share their views and experiences, and more readily utilise available forms of help. A focus is required on building relationships as early as possible, recognising that there is no single blueprint for a good relationship, and allowing them to evolve and be responsive to any changes in individuals’ circumstances; the optimum relationship can be challenging and/or supportive at different points in time. Crucially, each individual’s strengths and challenges will be different, shaped by their own personal characteristics, experiences, and circumstances, and we should not seek to predict exactly how each one-to-one relationship should look.

Relationship-centred practice in probation

The ‘core correctional practices’ literature within probation distinguishes two kinds of skills: (i) relationship skills and (ii) structuring skills. In terms of the former, positive relationships are characterised by care, empathy, enthusiasm, a belief in the capacity to change, and appropriate disclosure. In line with working alliance principles, and their own professional identities, probation-based intervention facilitators have underscored the importance of: adopting a non-judgemental approach; humanising the clients they work with; and having the time and skills necessary to support them. Practitioners have also highlighted the need to continually focus upon the balance between encouragement and ‘pushing’, and to be supported in using dynamic approaches which relate to the motivations of each individual.

Two sets of practitioner skills

People on probation have highlighted the importance of real collaboration and co- production. They stress that any initial decision to change their lives has to be theirs, but individual practitioners can help to keep them motivated to want to keep working on issues and to seek out solutions and suitable help through problem-solving advice. Continuity of support is so important – people benefit from the establishment of trusting relationships and have reported disliking ‘pass-the-parcel’ case management or having to repeat the same information to a succession of ‘strangers’. This is recognised within the Probation Professional Registration Standards which state that practitioners should:

Relationship-centred practice in youth justice

The following important factors have been identified for the work between practitioners and children in youth justice:

- practitioners demonstrating genuine care for, empathy with, and belief in, the children they are working with

- time, space and the prioritisation of relationships when working with those who have experienced trauma, abuse, loss, and negative experiences of relationships and professional involvement

- building the relationship as early as possible and allowing it to evolve in line with changes to the child/family situation

- recognising that every relationship is different and that there is no single blueprint for a good relationship.

In Northern Ireland, the Youth Justice Agency Model of Practice sets out seven components, the third of which is ‘relationship-based’, stating that these relationships should be ‘based on meaningful engagement, empowerment, respect, honesty, trust and optimism.’ Similarly, in England and Wales, the relationship-based practice framework for youth justice highlights the value of establishing relationships that are non-blaming, optimistic and hopeful, open and honest, and empathetic. There is also the IDEAS framework for effective practice which comprises the five interlinked elements of influence, delivery, expertise, alliance, and support, with the ‘alliance’ component capturing the ability to develop trusting relationships with children and their personal and professional networks.

Crucially, children want someone they can trust and who is reliable, and they also want to be able to feel they can manage what they are being asked to do. This is seen as particularly necessary when working with children who may, for a number of reasons, have a fear of authority. ‘Tuning-in’ and offering an empathic response, without judgment, whilst not colluding, can help children feel listened to and validated, all important factors to help children to develop agency and a sense of self-efficacy. In one study in Scotland, children identified that positive experiences of the youth justice system involved having a practitioner who:

- had a belief in them

- had a vision or belief in their futures

- were there during their worst spells as well as better ones

- helped them to understand their choices

- went ‘above and beyond’.

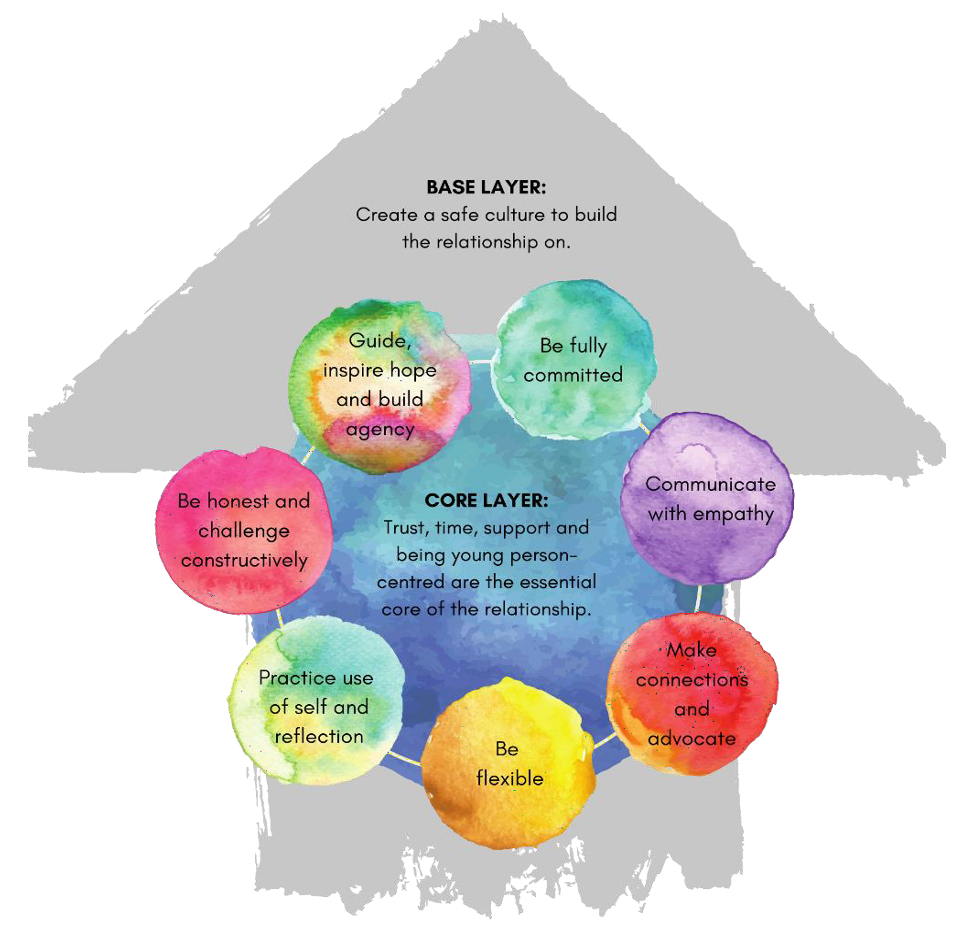

Finally, an evidence synthesis and a three-year action research project in the Republic of Ireland has led to the creation of a Relationship Model (with accompanying guidance) which can be used as a reflective resource by practitioners and their managers. As set out in the visual below, the model includes:

- a base layer of creating safety

- a core layer of ‘trust, time, support and being young person centred’

- seven grouped skills, attributes, and methods that can be applied at various points.

The model does not attempt to account for every eventuality, recognising that relationships by their nature are dynamic and diverse, but it does provide evidence-informed signposts and pointers for youth justice practitioners to follow when trying to build successful and effective relationships.

Relationship Model (O’Meara Daly et al., 2025)

Relationship-centred practice with differing groups

The importance of relationship-centred practice has also been highlighted in relation to specific sub-groups, as demonstrated by the following examples.

Approved Premises residents: In approved premises, the importance of establishing and maintaining safe and supportive relationships between staff and residents has been stressed, with residents highlighting the importance of staff availability and respectful day- to-day interactions.

Restorative justice participants: the relationship between a restorative justice (RJ) facilitator and RJ participants is crucial, and RJ should only be delivered by those who are sufficiently trained in facilitation, encompassing conflict resolution skills and the specific requirements of working with vulnerable people. In its 2018 practical guide to implementing RJ with children, the International Juvenile Justice Observatory highlight a number of further considerations when working with children, relating to language, posture, tone of voice and clothing, highlighting the level of specialism and forethought required.

People with personality disorder: The offender personality disorder (OPD) pathway is a long-term change programme that commissions treatment and support services nationally for people with ‘personality disorder’, whose complex mental health problems are linked to their serious offending. One of the key underpinning principles is that all services adopt a relational approach, in both external and internal aspects, aligning to the evidence supporting relationships as mechanism of change. There is a promotion of relationships based on reliability, consistency, curiosity, flexibility, and authenticity.

Care-experienced children have reported valuing the positive relationships which can be established with youth justice practitioners. The component aspects of building these relationships have been identified as: consistency and perseverance; being flexible and thinking holistically; and being child-centred and empathetic. Children have cited non- judgmental and consistent support as important, and particularly like aspects of work which are active and engaging. They also value the ability of practitioners to foster optimism for their futures.

Children with safeguarding needs: a trusting relationship between practitioner and child is also key to effective safeguarding work. Children with safeguarding needs require adults who are persistent, reliable and consistent in their relationships. Children need to know that the practitioner is not deterred by challenging behaviour, that the practitioner is on their side, and that the relationship requires no form of payback. They need workers who are friendly, flexible, persevering, reliable and non‐judgemental.

Victims: many of the elements of high-quality work with victims are the same as those for working with people who have offended, including the need to establish positive, secure, consistent and trusting relationships, and to consult and collaborate in establishing goals and finding solutions.

Key references

Bell, K. and Smerdon, H. (2011). Deep value: a literature review of the role of effective relationships in public services. London: Community Links

Brierley, A. (2021). Connecting with Young People in Trouble: Risk, Relationships and Lived Experience. Hook: Waterside Press.

Creaney, S. (2014). ‘The position of relationship based practice in youth justice’, Safer Communities, 13(3), pp. 120-125.

Dominey, J. and Canton, R. (2022). ‘Probation and the ethics of care’, Probation Journal, 69(4), pp. 417-433.

Dowden, C. and Andrews, D.A. (2012). ‘The importance of staff practice in delivering effective correctional treatment: a meta-analytic review of Core Correctional Practice’, International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 48(2), pp. 203-214.

Evans, R. and Szifris, K. (2024). ‘Relationship- based work with children in the youth justice system’, in Wigzell, A., Paterson-Young, C. and Bateman, T. (eds.) Desistance and Children: Critical Reflections from Theory, Research and Practice. Bristol: Policy Press.

Fullerton, D., Bamber, J. and Redmond, S. (2021). Developing Effective Relationships Between Youth Justice Workers and Young People: A Synthesis of the Evidence. REPPP Review, University of Limerick.

Haas, S.M. and Smith, J. (2020) ‘Core Correctional Practice: the role of the working alliance in offender rehabilitation’, in Ugwudike, P., Graham, H., McNeill, F., Raynor, P. Taxman, F.S. and Trotter, C. (eds.) The Routledge Companion to Rehabilitative Work in Criminal Justice, London: Routledge, pp. 339-351.

Horvath, A.O. and Luborsky, L. (1993). ‘The Role of The Therapeutic Alliance in Psychotherapy’, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 61(4), pp. 561–573.

Nahouli, Z., Mackenzie, J.-M., Aresti, A. and Dando, C. (2023). ‘Rapport building with offenders in probation supervision: The views of English probation practitioners’, Probation Journal, 70(2), pp. 104-123

Raynor P., Ugwudike, P. and Vanstone, M. (2014). ‘The impact of skills in probation work: A reconviction study’, Criminology and Criminal Justice, 14(2), pp. 235-249.

Trotter, C. (2013). ‘Reducing recidivism through probation supervision: what we know and don’t know from four decades of research’, Federal Probation, 77(3), pp. 43 – 48. Ugwudike, P., Raynor, P. and Annison, J. (2018). (eds) Evidence-Based Skills in Criminal Justice. Bristol: Policy Press.

Last updated: 31 January 2025