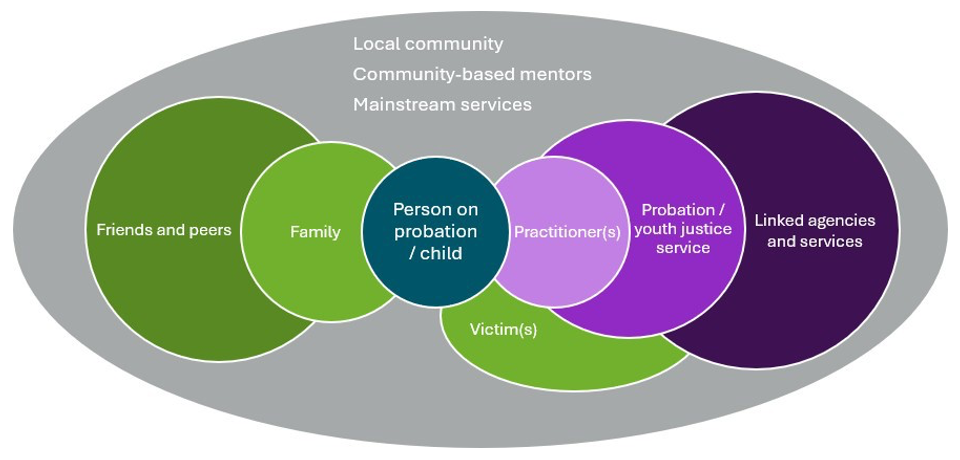

To properly promote and support relational and relationship-centred work, we must first understand the key relationships, the interrelations between them, and under what conditions they form and thrive. Crucially, when it comes to relationships, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Relationship mapping is one helpful technique, visually representing the connections between different entities within an ecosystem.

Relationship mapping in probation and youth justice

A visual map for probation and youth justice is set out below, capturing the practitioner, organisational, system, and community levels. As is also set out within the visual, for children within the youth justice system and for people on probation, close attention needs to be given to their primary relationships with family members and with friends and peers. After all, it is not just professional relationships that can have a positive/protective effect.

Relationships map for probation and youth justice

The following two case examples from our core inspection programmes help to illustrate the value of thinking holistically and establishing a broad range of positive connections and relationships.

Case examples

Daniel was a 15-year-old male who had received a community resolution for the offences of criminal damage and harassment towards the police. The practitioner engaged well with Daniel and with other professionals, and the assessment drew on information from various sources, reviewing the existing key areas of support (NSPCC, school, social care, child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS), and placement care/staff).

This led to a detailed and analytical assessment of Daniel’s needs and the factors impacting upon his behaviour, including analysis of childhood experiences and consideration of how these had the potential to expose Daniel to harm. It was decided during the planning stages that joint work between NSPCC and CAMHS would be appropriate, and existing controls and interventions were reviewed.

The planning was collaborative, and objectives were supportive of the learning needs and emotional wellbeing of Daniel. Interventions were then delivered to support the safety of Daniel and focussed on managing emotions, conflict, peer pressure, and child criminal exploitation. Sessions were adapted to meet Daniel’s learning needs and style, and professionals communicated well and shared information. The careers worker undertook sessions with Daniel and supported his applications for future learning. A speech and language assessment was also undertaken and shared with other professionals.

Will was a 24-year-old male of mixed White and African Caribbean heritage sentenced to custody for Class A possession with intent to supply and possession of a bladed article. There was a known history of gang affiliation and serious knife crime, and there were risks associated with Will returning to his home area. Will’s willingness and ability to engage was analysed and understood and his voice was present throughout the assessment.

The practitioner worked hard to understand the impact of previous negative experiences on his engagement, and prioritised building a trusting relationship to overcome the barriers to compliance caused by previous experiences of discrimination. Strengths and protective factors were identified; these included a supportive and pro-social relationship with his mum, previous maintenance of an independent tenancy, goals and aspirations, and support from the Leaving Care Team.

The resettlement work that was undertaken was particularly good, and referrals were supported through liaison with Will’s leaving care worker. The practitioner advocated for Will and secured accommodation in the local area which mitigated the risks associated with returning to his home area. The practitioner focused on progress and used this to support reviewing activities in conjunction with Will.

She undertook “how far have you come” exercises at different stages of supervision to help him identify progress and maintain motivation, developing positive aspirations and discrepancies between goals and current behaviours. There were early positive outcomes relating to ETE and accommodation, and some progress in terms of a positive shift in attitudes, thinking and behaviours.

Primary relationships with family members and with friends and peers

The value of positive family relationships is very evident within the research literature, with families potentially being powerful allies. Research has demonstrated that families can:

- help to build understanding of an individual’s characteristics, experiences, and circumstances

- provide motivation and support to cease offending

- help with adherence to treatment and supervision requirements

- encourage self-belief and engender hope in the possibility of change

- widen access to information and resources, especially employment and housing.

Case examples

Alison was a 34-year-old female sentenced to a custodial sentence for theft and drug-related offending. During the inspection period, Alison was recalled once on home detention curfew (HDC) and three times on licence. She was also convicted of a further acquisitive offence which was committed on her first release on HDC.

There were positive attempts to complete pre-release work and appropriate referrals were made on behalf of Alison. The pattern of release and recall led to an increased focus upon the reasons for non-compliance. Whilst trying to locate Alison as part of a recent alternative to recall, the probation practitioner contacted her sister, who had been identified as her emergency contact.

The subsequent discussions enabled the probation practitioner to understand more about Alison, including her trauma associated with her childhood and her experience of sexual abuse. It also led to the development of a protective factor, with Alison re-establishing contact with her family and Alison’s sister visiting her whilst in custody.

Visualising family and social networks through an eco-mapping approach can illuminate sources of family support (recognising that people’s understandings and experiences of ‘family’ will differ) and wider community supports. The video below provides a helpful overview of eco-mapping, explaining how it can build relationships through meaningful dialogue and working together, while also building an agreed understanding of both resources and needs.

Disclaimer: an external platform has been used to host this video. Recommendations for further viewing may appear at the end of the video and are beyond our control.

The 2019 Farmer Review concluded that relationships were very important to women, affecting the likelihood of reoffending ‘significantly more frequently than is the case for men’. Women are more likely to be primary carers of children, and a large proportion of those in the criminal justice system have been victims of domestic or other abuse. Farmer thus argued that relationships are the ‘foundation stone’ that a woman can ‘build her new life upon’, and that all women need this to be an explicit element in their rehabilitation, even more so where relationships are identified as criminogenic.

Within youth justice, there is evidence that positive peer relationships and positive parent-child, sibling and wider family relationships can all help to provide safety. When thinking about building resilience for children who are being exploited, including through gang involvement, it has been highlighted that interventions need to target reducing or removing the negative influence of exploiters and increasing positive protective relationships to increase relational resilience and decrease systemic trauma. Amongst a variety of parenting variables, behavioural control and warmth have been found to be the most powerful aspects of moderating the relationship between gang involvement and problematic behaviour. Parental ability to provide external barriers through supervision, monitoring and involvement can deter potential abusers outside the family home, as can parental work to promote self-efficacy, competence, wellbeing and self-esteem which can make a child less likely to be targeted for abuse and more likely to speak up if they are abused.

Key references

Jardine. C. (2017). The role of family ties in desistance from crime. London: Families Outside.

Lord Farmer. (2019). Farmer review for women. London: Ministry of Justice.

Rutter, N. and Barr, U. (2021). ‘Being a ‘good woman’: Stigma, relationships and desistance’, Probation Journal, 68(2), pp. 166-185.

Shapiro, C. and DiZerega, M. (2010). ‘It’s Relational: Integrating Families into Community Corrections’, in McNeill F., Raynor P. and Trotter, C. (eds.) Offender Supervision: New Directions in Theory, Research and Practice. Cullompton: Willan.

Last updated: 31 January 2025