Effective Practice Spotlight: The Probation Service – Yorkshire and the Humber region

Yorkshire and the Humber effective practice summary (Back to top)

HM Inspectorate of Probation’s definition of effective practice is ‘where we see our standards delivered well in practice’.

- Fieldwork took place in each Yorkshire and the Humber Probation Delivery Unit (PDU) between 01 July 2024 and 25 October 2024.

- We reviewed 546 cases, 327 of which were subject to a community sentence and 219 to release on licence.

- We also reviewed 299 court reports and 209 cases subject to resettlement provision.

- We inspected 47 unpaid work (UPW) cases and 60 statutory victim cases from across the region where community sentences and licences had commenced between 04 Dec 2023 and 07 April 2024.

- The strongest practice across the majority of PDUs was the assessment and planning for engagement of the person on probation. We also found the planning to reduce reoffending and support desistance to be a strength in most PDUs.

- We found 140 pieces of effective practice within domain two casework.

- We found the most effective practice across multi-agency working and information sharing, pre-release/resettlement work, and interventions.

In this spotlight report, we have highlighted the strongest case examples of effective practice from each PDU, across several themes related to case management.

Our standards (Back to top)

These are the HM Inspectorate of Probation standards met by the examples of effective practice selected from across Yorkshire and the Humber. A full list of our standards, plus further reading and research, can be found on our website.

- Staff are enabled to deliver a high-quality, personalised, and responsive service for all people on probation.

- A comprehensive range of high-quality services is in place, supporting a tailored and responsive service for all people on probation.

- Assessment is well informed, analytical, and personalised, actively involving the person on probation.

- Planning is well informed, holistic, and personalised, actively involving the person on probation.

- High-quality, well-focused, personalised, and coordinated services are delivered, engaging the person on probation.

- Reviewing of progress is well informed, analytical, and personalised, actively involving the person on probation.

Court work (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Inclusive risk assessment at court stage

Hamza, a 24-year-old Pakistani man, was sentenced to a community order, rehabilitation activity requirement (RAR) days, and a restraining order (RO) for familial domestic abuse (DA). He had a history of DA and non-molestation order breaches.

Strong court assessment and analysis:

- There were detailed DA and safeguarding police enquiries.

- Telephone contact took place with the allocated social worker, and an interview with Hamza.

- The pre-sentence report (PSR) drew on family intelligence and mental health history.

Diversity considerations:

- These were evident at a personalised and national level relating to his Black, Asian, and mixed heritage background.

- Family dynamics, family-based trauma, and disproportionality were explicit in the PSR.

- Strengths including motivation and past compliance were included.

Outcome: This full assessment and PSR provided a comprehensive analysis of the case to inform the court.

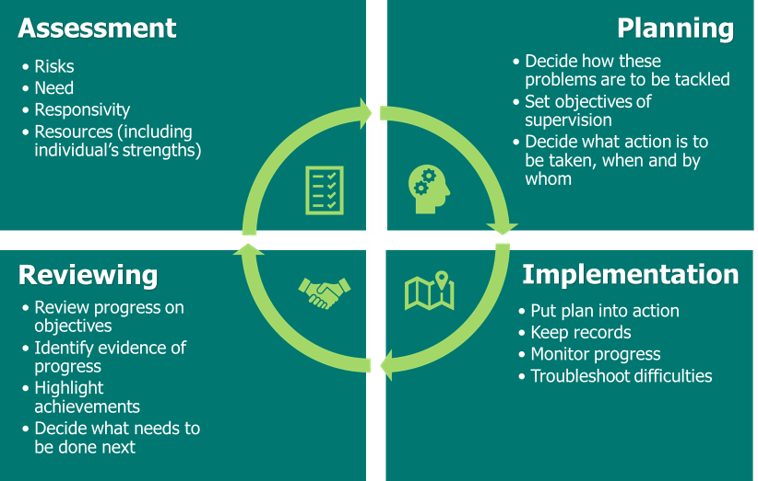

The ASPIRE model of case supervision (Back to top)

‘Contemporary probation practice is based upon the ASPIRE model of case supervision. In our core inspections, we judge the quality of delivery in individual cases against this model’.

In the case example below, we saw evidence of effective practice across all elements of the ASPIRE model.

Example of effectiveness: Inclusive risk assessment at court stage.

Nigel, a 45-year-old man, was sentenced to custody for DA against his partner, with alcohol as a recurring factor. He was given an RO. He had a history of DA, including physical violence and weapon threats, and had been previously supervised by probation services.

Strong assessment and planning:

- Analysis took place of past behaviour, substance misuse, and emotional regulation.

- Childhood experiences of witnessing abuse and local authority care were considered.

- A spousal assault risk assessment, police enquiries, and victim liaison officer (VLO) evidence were used to assess risk holistically and consider licence conditions.

- Safeguarding enquiries were completed at court and pre-release.

- The risk management plan was developed collaboratively with partner agencies, the VLO, and the police.

Collaborative implementation and delivery:

- Challenges associated with an exclusion zone with partners were addressed.

- Oversight by two local authorities.

- There was prompt support during periods of homelessness.

- The skills for relationships toolkit (SRT) aided behaviour reflection.

Outcome: Nigel’s engagement was supported through personalised probation service delivery. Contacts with two probation practitioners (PPs) helped him access employment, accommodation, and emotional regulation support. Upon eligibility for Probation Reset his case was reviewed, and referrals ensured a smooth exit plan.

Risk assessment (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Risk assessment using a range of sources

Graham, a 39-year-old man, was sentenced for a public order offence involving a weapon. He was assessed as very high risk of harm, and with significant mental health issues, including bipolar disorder and psychosis, worsened by non-compliance with medication and substance use.

Clear understanding of current and previous offending:

- There was consistent support during resettlement, via video links and multi-agency coordination.

- Assessment considered all personal and mental health factors, involving Graham.

- Motivation, readiness for interventions, and impacting factors were identified.

- Analysis drew from all available sources of information, including psychology reports and offender personality disorder consultations.

Outcome: Graham’s assessment of risk had a clear rationale. Case records showed an understanding of the context, likelihood, and targets of the risks. All risk factors were identified and analysed, informed by a wide range of sources.

Example of effectiveness: Holistic risk assessment and engagement

Jeff, a 26-year-old man, was sentenced for drug-related offending. Assessed as medium risk of serious harm, and with complex neurodiversity needs, low levels of maturity, and experience of significant trauma, all contributing to substance abuse and mental health difficulties.

Significant efforts to understand individual needs:

- Responses to the self-assessment questionnaire were considered, to understand factors impacting his engagement.

- Learning needs and mental health were given full consideration.

- Analysis incorporated a mental health assessment completed for a mental health treatment requirement.

- Assessment also recognised his vulnerabilities regarding peer influence and relationships.

Outcome: Evidence showed that Jeff was actively involved in the process. The assessment thoroughly considered potential triggers for Jeff to cause harm, and provided analysis to understand who might be at future risk of harm and how this also linked to potential self-harm by Jeff.

Public protection work (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Pre-release contact and engagement to build relationships and plan for resettlement

Sean, a 37-year-old Black British man, was approaching release after serving a long custodial sentence for violent offences. He had a history of violence and DA, and had been assessed as presenting a high risk to partners and the public.

Holistic communication and information gathering to support resettlement:

- Video links and three-way meetings with the prison offender manager (POM) were utilised.

- Regular telephone and email communication was maintained.

- Sean’s experiences within the care system, trauma, and discrimination were acknowledged.

- There was an in-depth analysis of factors linked to his offending.

- Offending and desistance needs were evaluated, highlighting strengths, motivation to remain offence-free, commitment to employment and training, and desire to reconnect with his children.

- Assessments were informed by prison behaviour and intelligence, identifying potential relationship risks.

- Previous relationship records and general offending behaviour were analysed.

- Safeguarding and police enquiries were conducted and analysed to inform the release risk management plan.

Outcome: The assessment identified specific victims and the nature and likelihood of risk, using all relevant sources. Sean was prepared for resettlement through his relationship with his PP and was directed to reside at an approved premises (AP) as part of his licence conditions. He fully understood the risk assessment and management measures, supporting his compliance and community engagement.

Example of effectiveness: A multi-agency approach to safeguarding a child and partner.

Kris, a 38-year-old man, was subject to a custodial sentence for shop theft. He was a habitual class A substance user with a significant number of convictions. He was released and recalled within two days, and was released on post-sentence supervision (PSS) for just a few weeks.

Well-managed resettlement period, with effective POM–community offender manager (COM) communication:

- There was good planning, with actions addressing risk and desistance factors.

- There was good contact between the PP and Kris.

- When Kris disclosed a new relationship following recall, the PP ensured that details were shared for police and children’s social care (CSC) enquiries.

- CSC referral led to safeguarding actions, including child removal, supervised contact, and non-contact agreements regarding Kris.

- Clare’s Law disclosure[1] was offered to his new partner.

- Kris was refused permission to reside at his partner’s address during PSS. There was a managed move into his partner’s address with CSC involvement before termination of the supervision period.

Outcome: Kris complied fully though his PSS through to termination. This was a well-managed case, with effective response to new information, inter-agency working, and the PP demonstrating professional curiosity to manage risk effectively.

Example of effectiveness: multi-agency liaison, information sharing, and contingency planning.

John, a 32-year-old man, was sentenced to a short custodial term for offending against his ex-partner. He had a long history of DA against multiple partners. He received another custodial sentence for harassing the same victim, was recalled after release, and received a further sentence for breaching a non-molestation order.

Focus on release, ensuring appropriate measures were in place:

- Risk increased from high to very high.

- There was prompt sharing of information with all involved agencies, including the police, CSC, and the POM.

- A multi-agency risk assessment conference, multi-agency public protection arrangements (MAPPA), and professionals’ meetings ensured that all agencies were accountable and involved in managing this complex case.

- The PP proactively engaged John after the further offence and recall, communicating via video link and email.

- The PP was transparent in reviewing behaviour, setting boundaries, and ensuring that John understood his risk assessment, release plans, and CSC compliance.

- Prompt AP referrals were made, and the PP requested a bespoke licence condition for a curfew and reporting times, to restrict John’s liberty and protect all known victims.

Outcome: The assessment identified specific victims and the nature and likelihood of risk, using all relevant sources. John was prepared for resettlement through his relationship with his PP and was directed to reside at an AP as part of his licence conditions. He fully understood the risk assessment and management measures, supporting his compliance and community engagement.

Example of effectiveness: Robust resettlement planning and activity prior to release.

Riyad, a 35-year-old Bangladeshi man, received an indeterminate sentence for public protection, with a minimum tariff of seven years, for sexual and violent offences. He transferred through the prison system, completing several interventions.

- Public protection planning and communication:

- The COM made timely referral to an AP ahead of the parole hearing, and Riyad received a release direction seven weeks later.

- Riyad was allocated to a psychologically informed planned environment (PIPE) AP with extensive pre-release activities: offender personality disorder pathway support, a video-link meeting with the AP key worker, and coordination of resettlement practicalities (bank account, NHS registration).

- There was ongoing communication between the COM and the prison, evident from contact logs, parole documentation, and reports.

- CSC and police enquiries were made before release.

- Riyad was informed at each stage and understood his licence conditions, including additional conditions.

Outcome: Riyad was released to a PIPE AP with an electronic monitoring tag and was subject to additional licence conditions restricting movement and contact, and with enforced drug and alcohol tests and polygraph testing.

Interventions (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Use of an interpreter to support language barriers.

Farzan was a 43-year-old man from Iran. He spoke Farsi and had limited English. He was sentenced to a suspended sentence order, with RAR days and an alcohol monitoring requirement. His offences were of a sexual nature against a stranger.

Well-managed case, with consistent interpreter support:

- Farzan would text when he needed to talk to his PP, and the PP would arrange interpreter services for all calls to ensure good communication.

- Translation of JobCentre Plus and court fine information through the interpreter was facilitated during supervision.

- The self-assessment questionnaire was translated into Farsi.

- The PP visited Farzan jointly with members of the public protection unit, and prompted them to translate sex offender registration conditions.

- Relationship building and practical support with overcoming language barriers.

- Maps for Change[2] was adjusted to use discussions instead of worksheets, to address language barriers.

Outcome: There was a positive focus on language barriers for Farzan which enabled him to engage and understand the expectations of his order. All aspects of his order were completed, including the alcohol monitoring requirement, without issue.

Example of effectiveness: Positive delivery of services to support desistance.

Emma was a 49-year-old woman who received a short custodial sentence for shop theft, a violent offence, and harassment. Emma committed the thefts in local supermarkets and retail stores, and assaulted members of staff when apprehended. She had a history of acquisitive crime to fund her substance misuse, and on occasion had used violence against police and security staff. She had previously been subject to community orders; the orders were revoked due to further offending and poor compliance with services.

Good understanding of diversity and needs:

- The PP displayed a consistent approach to reviewing barriers and exploring additional support pathways.

- The COM carried out good pre-release work with Emma.

- Needs, available services, and treatment plans were sufficiently assessed prior to release, and reviewed on release.

- There was good partnership working with mental health and substance misuse services and local charities, monitoring Emma’s engagement.

- Stable housing was secured, and professionals worked together to build confidence and support independent living skills.

Outcome: This case demonstrated positive delivery of services, with strong partnership work and well-informed reviewing. Emma was a Probation Reset case and, as part of termination planning, support was still offered from women’s services. The PP attended the women’s centre weekly, so she remained visible and still able to monitor Emma’s progress.

Example of effectiveness: Delivery of the SRT.

Will, a 27-year-old man, received a community order for DA offences. This was his first experience of probation supervision, so his level of engagement was unknown.

- The PP developed a positive plan to engage him prior to each RAR session:

- There was effective implementation of the sentence plan and delivery of interventions.

- UPW started promptly, and a referral to commissioned rehabilitative services for accommodation support encouraged engagement and built a positive relationship before addressing offending behaviour.

- The PP followed a consistent structure in each session, facilitating the SRT, with check-ins, recaps, and summaries of expected learning.

- Each session involved in-depth discussions, with Will providing examples of applying the learning and reflecting on it.

Outcome: There were no issues with engagement throughout Will’s order. During a home visit, his mother remarked on the discussions they would have about the skills he had learned during sessions.

Example of effectiveness: Partnership working with an alcohol support service.

Colin, a 58-year-old man, was sentenced to a community order with RAR days and a curfew for offences of improper use of telecommunications while intoxicated. He was alcohol dependent, with a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and had mobility issues.

Positive engagement with person on probation and partner agencies:

- The PP ensured that Colin completed the self-assessment questionnaire, considering his mental health and alcohol use. His views on offending behaviour and his personal circumstances were also considered in the assessment.

- Effective engagement methods were used, including telephone calls and home visits.

- Positive work on alcohol use included a 12-session action plan from a local alcohol support service, with evidence of effective co-working with the PP.

- The PP considered Colin’s diversity needs and alcohol use, tailoring appointment times, coordinating with his alcohol support worker, sending text reminders, and maintaining regular contact.

- There was regular liaison with the alcohol support team to support desistance work.

Outcome: The intervention helped Colin achieve abstinence and he began to consider voluntary work and peer mentoring.

Example of effectiveness: A trauma-informed approach to work with a young adult.

Jack, an 18-year-old man, was sentenced to a community order for a violent offence, having previously received a youth conditional caution. He had experienced significant trauma from a childhood in the care system and was diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, PTSD, and Tourette syndrome.

- The PP assessed his neurodiversity, low maturity, and vulnerabilities, identifying him as a vulnerable young adult:

- A tailored UPW placement was created, with a trauma-sensitive approach.

- The PP and UPW team collaborated to find a suitable placement with closer supervision and support.

- Plans were made collaboratively with Jack and his carer.

- Interventions were personalised, taking place in informal settings such as the local activity hub, cafés, and ‘walk and talk’ sessions.

- Offending behaviour work focused on strengths, goals, and developing a positive identity.

- Desistance work included access to resources like a computer, bicycle, and boxing lessons, with support from partner services.

Outcome: Working in a creative, trauma-informed way encouraged Jack’s engagement. He completed his UPW hours with the support offered, and the use of local community services ensured that he could access continued support when his order expired.

Unpaid work (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Planning for diversity needs when attending UPW.

Consideration of diversity needs when planning for UPW:

- The PP had clear conversations about not disclosing his offence, for his own safety, within the UPW setting.

- Plans were made regarding how Garry would manage himself at UPW if he found it difficult in relation to his autism.

- Religious prayer needs were planned for and an appropriate delay to commencing UPW was permitted to allow Garry to finish university work.

- The PP identified that a group would help him learn new skills and improve his fitness, which was a goal for him. Fitness training was used to help motivate him and reduce anxiety about being in the group.

- The PP implemented a texting system at the beginning of UPW sessions, to check in with him and confirm that he was settled.

Outcome: Garry completed UPW without any issues, due to the planning and preparation in place to meet his needs.

Victim work (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Good VLO advocacy for victim voice in planning exclusion zone.

David, a 65-year-old man, received a determinate custodial sentence for sexual offences against a child. The victim contact was with child’s parents and there was no mechanism for the family to submit a victim personal statement.

Managing expectations relating to imposition of an exclusion zone:

- The VLO liaised with the policy team, family, and PP to discuss the proportionality of a proposed exclusion zone.

- The VLO supported the family in making submissions about their rationale for the exclusion zone and its impact on their lives.

- The exclusion zone was a source of many discussions. The VLO balanced the family’s needs and the PP’s proposal.

- The victim’s family was informed of the final licence conditions before release, and these were implemented satisfactorily.

- The VLO handled any queries clearly and sensitively, maintaining a good relationship with the family.

- Expectations and contingency planning around the exclusion zone were established.

Outcome: The family was satisfied with eventual outcome, even though the exclusion zone was smaller than originally requested. The VLO maintained professional boundaries with the PP, despite differences of opinion.

Management oversight (Back to top)

Management oversight is a term used in the Probation Service to encompass the oversight of casework, staff wellbeing, and countersigning. During the thematic inspection, ‘The role of the senior probation officer and management oversight in the Probation Service’, and for the purpose of this spotlight report, management oversight is defined as follows:

‘… the formal process by which a manager, most often an SPO, [senior probation officer] assures themselves that operational delivery is undertaken consistently and to the required standard. This is in line with the definition used by His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS). Management oversight may include formal and informal meetings between the SPO and the probation practitioner (PP). Similarly, countersigning activities, such as those for the offender assessment system (OASys), are part of the management oversight framework.’

Below we share examples of where we saw effective management oversight of cases.

Example of effectiveness: Multi-agency working and escalating concerns.

- There was ongoing management oversight, with clear direction, proactive monitoring, and follow-up actions from the SPO.

- The SPO challenged non-attendance from the police at child protection meetings, ensuring that subsequent professionals’ meetings highlighted their involvement in protecting victims and better managed risk on the subsequent release.

- MAPPA meetings were held, with relevant actions given to the PP and agencies involved.

- The SPO followed up these actions with the PP to ensure that they were completed.

Outcome: This ensured that partners understood the importance of their involvement in protecting victims via professionals’ meetings, as well as holding them to account.

Example of effectiveness: Improving quality of assessments.

- Gaps in the initial assessment – including no evidence of DA enquiries or analysis of safeguarding information – were identified.

- The SPO prompted a deadline to be set and recorded review of the OASys assessment, contact with CSC, and a home visit.

- The SPO also collated information and learning guides to support the PP’s risk management and contingency planning – resulting in improved emphasis in these areas once the review of the OASys assessment was countersigned.

Example of effectiveness: Case allocation.

- The SPO summarised all the available child safeguarding and DA information during allocation, including details of children, known CSC involvement, the number/nature of DA incidents, the partner, and restraining orders in place.

- Management oversight highlighted any gaps in the information, and the action to be taken by the PP to obtain and assess that information.

- The SPO identified potential indicators of increasing risk and actions to be taken, and followed up actions for completion.

Outcome: The PP was conversant with the main DA and safeguarding concerns, and ensured that gaps in information were sought and informed the assessment, risk management plan, and ongoing supervision.

Example of effectiveness: Reviewing case.

- The new SPO reviewed specific cases in the team.

- Safeguarding work regarding children was clear, but in relation to partners was lacking.

- There was positive input from the SPO in addressing deficits in this case and providing greater understanding of the work undertaken to date.

- The SPO added a substantial number of nDelius entries summarising the case, with records having been very confused prior to this, and requested several relevant actions to take place, which were then followed up.

- The SPO provided clarity on several issues.

Outcome: The case highlights the benefit of thorough and effective management oversight and the importance of SPOs making their own judgements on the quality of work when quality assuring cases.

References and acknowledgements (Back to top)

This Effective Practice Spotlight is based on information sourced while undertaking our inspection of the Probation Service – Yorkshire and the Humber region. The manager responsible for this inspection programme is Dave Argument. Helen Amor, effective practice lead, has drawn out examples of effective practice from the inspection of the region. These are presented in this guide to support the continuous development of these areas in the probation region. We would like to thank all those who participated in any way during the inspection, and especially those who have contributed to this guide. Without their help and cooperation, the inspection and Effective Practice Spotlight would not have been possible.

[1] The Domestic Violence Disclosure Scheme (DVDS), also known as “Clare’s Law” enables the police to disclose information to a victim or potential victim of domestic abuse about their partner’s or ex-partner’s previous abusive or violent offending.

[2] Maps for Change (M4C) is a toolkit of exercises which practitioners can use to structure their supervision with adult men who have committed a sexual offence and are assessed as low risk of reconviction