Effective Practice Spotlight: The Probation Service – Wales region

Effective practice methodology (Back to top)

In our inspections of probation services in Wales, we assessed cases against our probation service delivery standards. Inspectors considered whether practice in selected cases was sufficient to meet the engagement and desistance needs of people on probation, and whether activity was sufficient to keep other people safe.

The overall service delivery ratings were calculated based on the percentage of cases that had been identified as sufficient against each of our key questions and standards.

Our definition of effective practice is ‘where we see our standards delivered well in practice’. We saw effective practice in a number of the cases inspected as part of fieldwork in Wales. This spotlight is designed to highlight where practice was effective.

Wales effective practice summary (Back to top)

- We carried out fieldwork in each probation delivery unit (PDU) across Wales between 28 July 2025 and 22 September 2025. We carried out regional fieldwork between 29 September 2025 and 27 October 2025.

- We reviewed 338 cases, 224 of which were subject to a community sentence and 114 to release on licence.

- We also reviewed 265 court reports and 107 cases that were subject to resettlement provision.

- We inspected 58 unpaid work (UPW) cases and 28 statutory victim cases from across the region where community sentences and licences had begun between 18 December 2024 and 24 March 2025.

- The strongest practice across all PDUs was in assessment and planning to engage the person on probation, reduce reoffending and support desistance. Most PDUs also demonstrated strong engagement of the person on probation in delivery and reviewing.

- We found 109 examples of effective practice in the domain two[1] casework.

- In this spotlight report, we have highlighted the strongest examples of effective practice from each PDU, across several themes related to case management.

Our standards (Back to top)

These are the HM Inspectorate of Probation standards, which were met in the examples of effective practice selected from across Wales. A full list of our standards, plus further reading and research, can be found on our website.

- Assessment is well informed, analytical, and personalised, actively involving the person on probation.

- Planning is well informed, holistic, and personalised, actively involving the person on probation.

- Staff are enabled to deliver a high-quality, personalised, and responsive service for all people on probation.

- A comprehensive range of high-quality services is in place, supporting a tailored and responsive service for all people on probation.

- High-quality, well-focused, personalised, and coordinated services are delivered, engaging the person on probation.

Organisational arrangements and activity (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: The Human Factors model

In 2022, Probation Service Wales introduced the learning organisation approach.[2] This is a model designed to support a shift towards an inclusive, open learning culture and improve safety. Built on an evidence base called Human Factors, it introduces new tools and ways of working to help mitigate bias and disproportionality in decision-making, improve communication and collaboration across teams, create time and space for reflection and learning, and support staff autonomy while maintaining accountability.

Human Factors applications:

- SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation): A structured communication tool that helps to provide clarity, promote autonomy and supported more considered decision-making.

- Protected hour (time): Dedicated time for managers and their staff to engage in reflective discussions, prioritise tasks, and manage workload effectively.

- Team briefings (checklist): Co-designed by managers and staff to identify stressors, risks, and errors, enabling timely problem-solving, escalation, and feedback.

- Monthly meeting (feedback, reflection, and learning): A direct line of communication from frontline staff to senior leaders to share successes and learn lessons through root cause analysis.

Senior leaders in Wales recognised the pressures on staff following significant national policy changes and that the learning organisation approach had helped to create a supportive culture that prioritised staff wellbeing, reflective practice, and decision-making. Managers reported that conversations were more focused and productive, enabling clearer decision-making. Practitioners felt empowered to take ownership of their work, and felt increasingly confident in solving problems independently. Protected time improved wellbeing by reducing stress and anxiety, allowing teams to function more effectively. Risk management was strengthened through increased reporting of risks and near-misses, supported by robust feedback loops. Importantly, the approach had driven a culture shift, reducing hierarchy and giving all staff a voice, and fostering collaboration and shared responsibility. Human Factors created a transparent, supportive environment that balanced autonomy with accountability. By embedding structured tools like SBAR and protected time, Wales Probation Service was driving a cultural reset that improved decision-making, wellbeing, and service quality.

Example of effectiveness: Leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) to reduce administrative tasks and improve engagement

As part of the HMPPS digital transformation strategy, Wales Probation Service had piloted several AI-powered transcription and summarisation tools designed to reduce administrative tasks and improve efficiency. The initiative aimed to free up practitioners’ time for meaningful engagement with people on probation while improving the quality and timeliness of case records.

Thees tools transcribed and summarised supervision meetings and frontline interactions, producing accurate summaries within minutes.

The pilots formed part of a wider strategy to reduce the administrative burden for probation practitioners (PPs), improve the quality and timeliness of records through automated transcription and enhance accessibility for staff with neurodivergent conditions or other needs by reducing cognitive load.

Pilots ran for 10–20 weeks, focusing on sentence management teams and key interactions such as induction appointments, sentence planning interviews, and supervision meetings. Implementation involved onboarding, training, and structured feedback loops.

Impact and benefits

The evaluation of one of the tools, ‘Minute’, highlighted significant gains:

- Tasks that previously took two hours were completed in 30 minutes, with the time spent on writing contact logs reduced by an average of 73 per cent.

- 96 per cent of practitioners reported that the quality of records had improved.

- 83 per cent of practitioners noted better engagement with people on probation during sessions, as they could maintain eye contact with them and actively listen.

- Pilot probation practitioners (N=24) rated AI-generated supervision summaries: Accuracy 4.27/5, Coherence 4.68/5, Fairness 4.55/5 (mid-pilot survey). In-app feedback from the same users showed 94 per cent satisfaction and +70 NPS.

- Over 3,000 frontline meetings were summarised during the evaluation window.

- Qualitative feedback from neurodivergent and disabled staff shows the tool reduced cognitive load by easing note-taking, supporting dictation, and freeing attention during sessions.

Practitioners described the tools as “fantastic – summaries are clear and accurate” and valued the ability to focus on listening rather than note-taking. They said this improved engagement with people on probation and freed up time for risk assessment and professional curiosity.

Sustainability and next steps

Following the pilots, Justice Transcribe was rolled out to all sentence management teams in Wales and KSS. It has additionally expanded to areas of London and plans are in place for scaling across all Probation Regions. To date, over 50,000 meetings have been transcribed. A full evaluation led by the Justice AI Unit will consider its impact on the service and its wider application.

By using AI technology, Wales Probation Service demonstrated how innovation can transform operational practice, creating capacity, improving service quality, and supporting a more person-centred approach. This aligns with the broader Probation Service strategy of embedding technology to improve outcomes for people on probation and as part of the ‘Our Future Probation Service’ programme to create a future-ready probation service by driving digital transformation, improving operational efficiency, and reducing probation workload to enhance service delivery and sustainability.

Please follow this link to hear staff feedback regarding the use of AI

Example of effectiveness: The Centralised, Operational, Resettlement, Referral and Evaluation (CORRE) Hub

The CORRE Hub was a key component of Wales Probation Service’s unified model. It acted as a central interface between PPs and the interventions landscape, which spanned public, private, and third-sector providers. Unlike in English regions, where digital solutions primarily support referrals to Commissioned Rehabilitative Services (CRS), the CORRE Hub in Wales managed a broader range of interventions, while incorporating the refer and monitor tool (intervention digital service).

Purpose

CORRE assisted PPs by:

- identifying suitable interventions

- enhancing the quality of assessment and sentence planning

- completing referrals quickly and accurately.

By removing time-consuming administrative tasks, the CORRE Hub enabled PPs to focus on supervision and engagement, leading to better outcomes for people on probation. During inspection, 77 per cent of reviewed cases had plans that focused sufficiently on reducing reoffending and supporting desistance, with some PDUs achieving even higher levels of sufficiency.

Key functions included:

- referral management: triaged, prioritised, and monitored referrals across internal interventions, CRS services, and community provision

- strategic influence: tracked referral volumes, identified gaps, and informed commissioning activity

- quality assurance: used quality assurance tools and reflective feedback loops to maintain high-quality work that met HM Inspectorate of Probation’s standards

- prompting: actively progressed accredited programme and UPW requirements, ensuring these were well sequenced.

In 2024, the CORRE Hub supported 9,036 sentence plans and processed 8,122 CRS referrals. Referrals were 50 per cent faster than the national average. The Wales assessment tool (WAT) report (July 2024) confirmed that CORRE sentence plans are more likely to engage individuals and reduce reoffending. Additionally, the Hub’s quality assurance activity continues to drive improvements in sentence planning and referral processes.

CORRE probation services officers (PSOs) maintained a Wales-wide directory of services. This made them a point of contact when expert knowledge was required, and enabled practitioners to offer tailored interventions, such as brain injury and autism support. The region reported good communication between PDUs and CRS suppliers, ensuring smooth delivery. Monthly CORRE reports tracked performance and informed continuous improvement.

The CORRE Hub created economies of scale, transferred the administrative burden from PPs to dedicated teams, and embedded strategic priorities into sentence planning. This approach ensured quality, consistency, and timeliness; it supported the ‘start right, end right’ agenda of the region and improved outcomes for people on probation.

Court work (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: A person-centred approach to pre-sentence report (PSR) recommendations

Barry, a 40-year-old man, was convicted of failing to provide a breath specimen. Safeguarding concerns were identified due to previous allegations of domestic abuse.

Comprehensive account of offending and circumstances:

- An oral PSR was completed on the day of sentencing, which demonstrated a high level of professional curiosity and analytical depth.

- Relevant safeguarding enquiries were returned and thoroughly considered, including police call-out records and child safeguarding information.

- Risk predictors were applied appropriately to support the assessment using the index offence and previous offending history.

Balanced and evidence-based approach:

- Barry actively participated in discussions about sentencing options, and his motivation to engage with interventions was assessed and documented.

- Barry’s level of responsibility was explored in detail, and the potential impact on his victims was considered.

- The PSR author took full account of Barry’s personal circumstances, particularly his role as the primary carer for three autistic children, adopting a trauma-informed and person-centred approach.

Outcome: The PSR was analytical and personalised. It effectively supported judicial decision-making by addressing reoffending risk and harm. It proposed a realistic, tailored community order (CO) that balanced Barry’s needs with his family responsibilities. He was sentenced to a CO, made up of UPW hours and a rehabilitation activity requirement (RAR), that was proportionate and deliverable within the context of his family obligations.

The ASPIRE model of case supervision (Back to top)

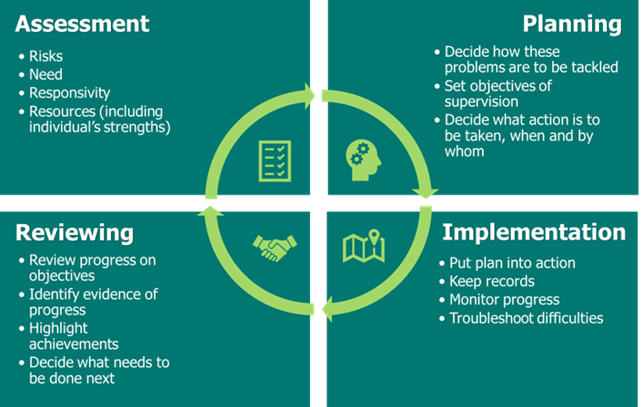

‘Contemporary probation practice is based upon the ASPIRE model of case supervision. In our core inspections, we judge the quality of delivery in individual cases against this model.’[3]

The four standards for inspection of adult case supervision follow the ASPIRE model by focusing on the quality of assessment, planning, implementation and review. Within each standard we assess the quality of engagement, work to address desistance and work to keep other people safe.

The following case examples demonstrate how PPs applied the ASPIRE model to deliver effective supervision. They highlight strong practice in risk assessment, safeguarding, multi-agency collaboration, and adaptive engagement.

Example of effectiveness: A well-informed and adaptive approach, prioritising public protection and supporting reintegration.

Terry, a 47-year-old man, was sentenced to a custodial sentence for breach of a restraining order.He failed to comply with restrictive measures and consistently pushed boundaries throughout his sentence, which led to recall.

- Thorough assessment and timely, coordinated resettlement planning:

- The PSR was thorough. It included safeguarding enquiries, and analysis of risk, desistance, and impact on the victim.

- Multi-agency resettlement planning addressed key needs such as accommodation, education, training and employment (ETE), and finance.

- Licence conditions and GPS tagging supported risk management.

- The assessment incorporated personal circumstances, diversity, and protective factors, with professional curiosity evident in exploring emerging concerns.

- Planning explored barriers such as rurality and transport.

- Proactive and responsive implementation and delivery:

- The PP maintained meaningful engagement, enforced swiftly, and coordinated CRS support from custody to community.

- Risk management was prioritised through licence variations and GPS tagging.

- Active and adaptive review:

- Risk management was updated regularly, with Terry’s input.

- A multi-agency public protection arrangements (MAPPA) Level 2 referral and oversight from a senior probation officer (SPO) ensured robust decision-making.

Outcome: This case demonstrated strong, consistent practice across all domains of supervision. Despite compliance challenges, the PP maintained a clear focus on risk management, desistance, and safeguarding.

Example of effectiveness: Planning and delivery that balanced engagement, desistance, and keeping others safe.

Emily, a 35-year-old woman, was sentenced to a CO with RAR days for offences involving violence. She presented with multiple and complex needs, including diagnoses of autism, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyslexia, anxiety, and depression. Emily was also identified as a vulnerable woman.

- Professional curiosity from the outset:

- The PP maintained a strong focus on safeguarding, and revisited domestic abuse and child protection enquiries throughout the order.

- Risk assessments were updated promptly in response to changes in Emily’s circumstances. They incorporated intelligence from partner agencies and Emily’s disclosures.

- Engagement and diversity-informed practice:

- The PP adapted their approach in response to Emily’s neurodiversity, building rapport through flexible, anxiety-reducing supervision options.

- Appointments were scheduled around Emily’s transport needs and held at a local women’s centre. This helped her to avoid overwhelming environments, and improved her attendance.

Intervention and multi-agency working:

- Emily engaged well with structured work at a women’s centre via CRS, supported by home visits and First Steps to Change sessions.

- Supervision was collaborative and transparent. The PP reviewed OASys with Emily to build trust and ownership.

- The risk management plan was robust, incorporating input from other agencies and prioritising victims’ safety through clear boundaries.

- Contingency planning was evident throughout, supporting consistent risk management.

Reviewing and risk management:

- The PP remained professionally curious and appropriately challenged Emily when a new alleged offence emerged.

- Ongoing risk reviews were informed by updates from the women’s service, ensuring that the sentence plan remained responsive to Emily’s evolving needs.

Outcome: Emily successfully completed her CO, supported by a flexible, trauma-informed approach and strong multi-agency collaboration. The case balanced engagement with risk management, leading to positive outcomes for Emily and the wider community.

Professional curiosity (Back to top)

Professional curiosity is essential to effective probation practice. It involves proactive questioning, critical thinking, and reflection to understand an individual’s circumstances fully. By looking beyond surface-level information and challenging assumptions, practitioners can better identify hidden risks and needs. This approach is especially important in safeguarding, where missed signs can lead to poor outcomes. We have highlighted in our inspections that a culture of curiosity, supported by supervision, open dialogue, and awareness of bias, enhances case supervision and decision-making.

Research carried out with probation professionals by Phillips et al. (2022) identified that practitioners’ understanding of professional curiosity fell into four broad categories:

- risk focused

- therapeutic

- knowledge building (improving the practitioner’s own knowledge)

- neutral (being generally questioning, ‘nosiness’).

While professional curiosity is often associated with assessing risk, its value extends far beyond this. Practitioners are encouraged to adopt a broader perspective, using curiosity as a therapeutic tool to build trust, explore individuals’ lives in depth, and support their own continuing professional development.

In the case examples below, we saw how professional curiosity underpinned effective, person-centred probation practice. In both cases, PPs went beyond surface-level engagement to uncover hidden risks and vulnerabilities. Their tenacity and proactive multi-agency coordination enabled them to respond robustly to safeguarding concerns, highlighting the critical role of curiosity in managing complex cases and protecting the public.

Example of effectiveness: Identifying exploitation through

professional curiosity

Jakub, a 59-year-old polish man, received a CO for having a knife in a public place and a separate driving offence. Jakub had grown up in Poland, so English was not his first language. He was offered an interpreter but declined, stating that he understood English. However, his comprehension appeared limited.

Strong initial assessment and engagement:

- The PP explored Jakub’s personal and diversity needs, identifying grief, isolation, and unstable housing as key challenges. Jakub engaged with the assessment, which highlighted concerns around loneliness, alcohol use, and job instability, all linked to his accommodation situation.

Identification of emerging concerns:

- The PP displayed strong professional curiosity, identifying Jakub as potentially vulnerable to modern slavery.

- A multi-agency safeguarding response was initiated, including police liaison, a multi-agency risk assessment conference (MARAC) referral, social care checks, and engagement with a specialist agency.

- Social care checks and contact with street outreach teams was undertaken when Jakub was out of contact.

- Jakub engaged with a specialist agency supporting victims of modern slavery.

- An interpreter was used to ensure Jakub understood the concerns when contact was re-established.

Effective risk management and enforcement:

- When Jakub disengaged, the practitioner took proactive steps to re-establish contact, identifying a new phone number, and noting signs that Jakub’s health was deteriorating.

- Breach proceedings were initiated, with re-engagement proposed if Jakub responded to the court summons.

Outcome: The PP demonstrated persistent curiosity and effective multi-agency working to safeguard Jakub, who was at risk of exploitation. The case highlights the value of curiosity and flexible, person-centred approaches in uncovering hidden risks and supporting vulnerable people.

Example of effectiveness: Managing risk through tenacious multi-agency work

Yasir, a 40-year-old Iraqi national, was initially given a suspended sentence order (SSO) with RAR days for driving offences. Due to persistent non-compliance, he was resentenced to custody. Yasir was assessed as posing a very high risk of serious harm. His case was highly complex, involving multiple aliases, conflicting information, and links to domestic abuse and organised crime. These factors hindered information-sharing and required a coordinated multi-agency response.

Proactive professional curiosity:

- The PP actively sought out and triangulated intelligence from a wide range of sources, including information on domestic abuse, risks to children, and organised criminal activity.

- The PP’s tenacity in liaising with multiple agencies was key to building a fuller picture of the risks posed.

Multi-agency coordination:

- New alleged offending and cross-border complexities emerged, presenting challenges to effective information-sharing across agencies.

- The PP submitted a MAPPA Level 2 referral. This ensured there was structuredmulti-agency planning and more information on safeguarding concerns, particularly those involving children.

- The PP liaised with prison services to support the implementation of communication monitoring. They collaborated with an independent domestic abuse adviser (IDVA) service to address evolving risks linked to Yasir’s circumstances.

- Yasir’s partner was encouraged to re-engage with safeguarding support for herself, including the use of target hardening measures in preparation for any potential release.

- A referral to the serious and organised crime unit was made due to concerns about Yasir’s associations, employment, and financial activity.

Outcome: Despite the challenges, the PP’s efforts led to better multi-agency coordination, improved safeguarding measures, and a clearer understanding of the risks posed. Yasir’s custodial sentence allowed for further risk management planning.

Public protection work (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Effective risk response in probation practice

Greg, a 33-year-old man, received a CO with RAR days for driving offences. This was imposed without a PSR. Greg had a complex history of violence and drug-related and acquisitive offences. He was diagnosed with ADHD and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Greg was assessed as posing a high risk of serious harm to children, the public, and a known adult. His risks were linked to organised crime, domestic abuse, and general violence.

Strong risk management:

- The PP responded promptly to reportable incidents and contextualised them within Greg’s risk profile.

- The PP took specific and timely action to safeguard others, including referrals to MAPPA and MARAC, liaison with the police, contact with the identified partner, and engagement with the IDVA and children’s services.

- The PP actively sought further information to inform decisions and ensure appropriate safeguarding responses.

Clear decision-making:

- Case notes and PP interviews evidenced a clear rationale for risk assessments and the actions taken.

- Management oversight was effective. Managers provided structured SMART targets that guided the PP’s response to emerging safeguarding concerns and escalating risks.

- The reportable incidents process supported multi-agency coordination. A MAPPA Level 2 referral led to joint meetings with children’s social care, which improved information-sharing and collaborative planning.

Outcome: This case illustrates how persistent information-gathering, multi-agency engagement, and responsive practice, underpinned by strong management oversight, can ensure that complex and evolving risks are managed effectively.

Example of effectiveness: Effective holistic safeguarding in case management

James, a 33-year-old man, was sentenced to a CO with RAR days, an accredited programme, and an alcohol abstinence monitoring requirement following a domestic abuse offence. He was assessed as posing a high risk of serious harm.

Effective safeguarding practice:

- The PP consistently demonstrated strong safeguarding practice.

- Risk to others was thoroughly assessed using the spousal assault risk assessment (SARA).

- The wider impact of James’s behaviour on his family, including his parents and young relatives, was carefully considered.

- Police call-out data was used effectively to inform risk assessments.

- Safeguarding enquiries were made across multiple local authorities.

- Open dialogue with James and his mother promoted transparency, informed decisions, and ensured a clear safeguarding audit trail.

Adult safeguarding:

- During a home visit, the PP identified James’s father as vulnerable and discussed a potential adult safeguarding referral with James’s mother. A referral was made, prompting a formal assessment of the family’s needs.

- The PP also considered the risk James posed to his parents due to his history of domestic abuse, taking a holistic and preventative safeguarding approach.

Timely interventions and multi-agency coordination:

- The PP made swift referrals to intervention services.

- James engaged with personal wellbeing services before beginning an accredited programme.

- The CORRE Hub process was used effectively, ensuring that referrals were actioned promptly and interventions were aligned with risk and need.

Outcome: The PP’s proactive safeguarding and coordinated planning supported James in completing his rehabilitative activities and staying engaged with services. Referrals addressed wider risks to James’s family, including a formal adult safeguarding assessment that strengthened protections around his father. The case illustrates how structured safeguarding and timely interventions can reduce risk and promote safer outcomes for individuals and families.

Multi-agency working and information-sharing (Back to top)

Effective multi-agency collaboration and timely information-sharing are central to robust probation practice, especially when working with individuals who present complex risks and needs. By coordinating with partners such as social care, health services, housing, and the police, PPs can develop a comprehensive understanding of risk, strengthen safeguarding, and provide tailored rehabilitative support.

Evidence shows that such collaboration improves outcomes by fostering shared accountability and enabling PPs to provide interventions that reflect the individual’s unique vulnerabilities and circumstances (Pycroft and Gough, 2019). Moreover, serious case reviews and public protection arrangements consistently highlight the critical role of information-sharing in preventing harm (Waring et al., 2022; Ministry of Justice, 2024). In probation, these practices are not just procedural, they are essential tools for managing risk, safeguarding, and supporting long-term desistance.

The case examples below illustrate how PPs used professional curiosity and coordinated multi-agency responses to safeguard vulnerable adults and children. They demonstrate how, through proactive engagement, thorough assessment, and responsive planning, person-centred practice can manage risk and promote rehabilitation

Example of effectiveness: A safeguarding response to complex and diverse needs

Evan, a 31-year-old man, was sentenced to a CO for an offence of arson, having set fire to some rubbish taken from a skip and placed in a bin. He had a long history of offending, and his behaviour reflected a fixation with tidiness and poor self-management, including risky actions such as burning waste and eating spoiled food.

Understanding support needs:

- The PP demonstrated a strong understanding of Evan’s complex needs, recognising the impact of neurodevelopmental issues, substance misuse, and self-neglect.

- The PP worked effectively with adult social care to secure supported accommodation for Evan, following capacity assessments.

- The PP contributed to multi-agency ‘self-neglect’ meetings, coordinating with housing, the police, health services, and prison staff to plan for Evan’s release.

- The PP considered Evan’s vulnerabilities, including neurodiversity, homelessness, and self-harm, to manage the risks to him.

- Strong communication and shared accountability across agencies enabled a holistic and preventative response.

Outcome: Evan’s case showed how effective multi-agency coordination is important in managing complex needs and escalating risk. Agencies worked together to address Evan’s trauma, neurodevelopmental challenges, and self-management issues. A tailored risk management plan was developed to reduce harm, prevent homelessness, and support stable reintegration.

Example of effectiveness: Effective practice in managing risk and safeguarding children

Henry, a 34-year-old man, was sentenced to a CO for violent offences, with a requirement to complete RAR days. He had no previous convictions or identified diversity needs, although personal circumstances related to employment were noted. He was assessed as posing a high risk, with active domestic abuse and child safeguarding concerns.

Safeguarding and professional curiosity:

- The PP demonstrated professional curiosity and vigilance throughout the case.

- On learning that Henry was living with a woman believed to be the victim of the index offence, the PP made an immediate referral to children’s social care and conducted a home visit to address the situation directly.

- These actions led to children social care becoming involved, and to effective multi-agency planning to safeguard the children.

Joint working and communication:

- Ongoing contact with the victim and the children’s school was maintained, especially when Henry disclosed information that conflicted with agreed safeguarding plans.

- A continuous feedback loop was established around Henry’s engagement and progress, which supported dynamic risk assessment and safeguarding.

- The PP’s proactive information-sharing contributed to a robust and protective plan for the children’s safety.

Outcome: The PP’s timely and coordinated response, underpinned by professional curiosity and effective joint working, led to strengthened safeguarding measures and a more protective environment for the children involved.

Example of effectiveness: Proactive safeguarding and

information sharing

Kenny, a 34-year-old man, was sentenced to a short custodial sentence for breach of restraining order. At the time of sentencing, he was subject to two concurrent orders. Safeguarding and domestic abuse enquiries revealed a history of police callouts involving the current victim and identified two children who had previous involvement with children’s social care.

Proactive and well-coordinated assessment and planning:

- The PP demonstrated a strong understanding of Kenny’s personal and criminogenic needs, including diversity considerations such as mental health and housing.

- Assessment activity was thorough and responsive, with professional curiosity evident in exploring emerging risks and safeguarding concerns.

Effective and timely information-sharing across agencies:

- The PP liaised with the police to ensure risk flags were placed on the victim’s address.

- The PP contacted IDVA services to confirm ongoing support would be provided for the victim.

- Reportable incidents were reviewed and recorded with care, which contributed to a robust approach to risk management.

- Efforts were made to establish Kenny’s accommodation status after CAS3 and to review his mental health needs.[4]

Strong Probation Reset delivery:

- There was meaningful engagement from Kenny and responsive action from the PP.

- The Probation Reset team demonstrated more than reactive management, with proactive safeguarding interventions and consistent review of risk.

- Multi-agency coordination, including the police and victim services, ensured that adults at risk were protected throughout the supervision period.

Outcome: Kenny’s case demonstrated how effective information-sharing and coordinated safeguarding responses within the Probation Reset framework can improve public protection and support rehabilitation. The PP’s proactive approach and strong interagency working were key to managing risk and maintaining the safety of victims and the wider community.

Equity, diversity, inclusion, and belonging (Back to top)

Effective probation practice increasingly embeds the principles of equity, diversity, inclusion, and belonging (EDIB), recognising that individuals under supervision often face intersecting disadvantages.

Research shows that inclusive, culturally competent, and trauma-informed approaches improve engagement and outcomes in probation. For example, neurodiversity-aware supervision and trauma-informed practice can reduce distress and enhance trust (Bradley and Petrillo, 2022; HM Inspectorate of Probation, 2023). Similarly, working with individuals from minoritised communities requires cultural humility and advocacy to challenge systemic barriers and promote equity (Wainwright et al., 2024).

The following examples illustrate how PPs embedded EDIB principles through thoughtful adjustments, multi-agency collaboration, and reflective supervision, demonstrating the transformative impact of inclusive practice.

Example of effectiveness: Supporting a neurodiverse individual on an SSO

Keith, a 27-year-old man, was sentenced to an SSO with RAR days and UPW for sexual offences. He had a diagnosis of autism and identified as bisexual. Post-sentence enquiries confirmed that there were no child safeguarding concerns, that Keith had no history of domestic abuse, and that he had no children.

Intervention and multi-agency work:

- The PP initiated requirements promptly, delivering Maps for Change and referring Keith to CRS for support with personal wellbeing, Careers Wales for ETE support and neurodiversity support.

- The PP worked closely with the Management of Sexual Offenders and Violent Offenders (MOSOVO) unit to manage risk collaboratively.

Inclusive practice and adjustments:

- The PP made adjustments to support Keith’s autism, including asking how he preferred to be supported, using visual aids, adapting the length and timing of sessions, and maintaining consistent scheduling to reduce distress and promote engagement.

- The PP engaged in self-directed learning through podcasts and criminal justice resources, enhancing their reflective practice and improving engagement with Keith.

Outcome: Keith engaged well with his SSO, showing progress in wellbeing and ETE. The PP’s neurodiversity-aware and trauma-informed approach supported sustained engagement, highlighting the value of structured support and supervision in complex cases.

Example of effectiveness: Supporting a person on probation from the Gypsy, Roma, and Traveller (GRT) community

Graham, a 36-year-old Welsh man from the GRT community, was sentenced to custody for drug-related offences linked to county lines activity. On release, his PP demonstrated a strong commitment to equity, diversity, and inclusion, ensuring that supervision was culturally informed and person-centred throughout the case.

Cultural sensitivity and respect for identity:

- The PP recognised the significance of Graham’s cultural identity as a member of the GRT community and created space for open, respectful dialogue about his heritage and values. This helped build trust and rapport, supporting more meaningful engagement.

Tailored interventions and respect for autonomy:

- Graham declined referrals to education, housing, and employment services due to cultural preferences. The PP respected his autonomy and prioritised culturally appropriate support. This person-centred approach reflected trauma-informed and anti-discriminatory principles, ensuring that practice was inclusive and respectful.

Multi-agency working and advocacy:

- The PP navigated complex safeguarding concerns linked to Graham’s residence on a traveller site with professionalism and cultural sensitivity.

- Multi-agency meetings with the police and housing services were coordinated, and Graham’s dignity was upheld throughout.

- Recognising the need for culturally competent advocacy, the PP signposted him to Gypsies and Travellers Wales[5] to support equitable access to services and challenge discrimination.

Management oversight and team learning:

- The case benefited from consistent management oversight, including group supervision, and SPO involvement in multi-agency meetings.

- The SPO supported the PP in navigating resistance from partner agencies while managing co-defendants from the GRT community. This fostered inclusive practice and a learning culture within the team.

Outcome: This case showed how culturally competent, reflective practice, supported by supervision and management oversight, can build trust, challenge systemic barriers, and promote equity in probation work.

Unpaid work (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Inclusive supervision and community integration

Nabil, a 40-year-old man originally from Eritrea, Africa, was sentenced to a CO for driving offences, including UPW and RAR days. Nabil had no previous convictions and had sought refuge in England. He was supported at his initial appointment by an interpreter. The PP explored his preferences, noting his motivation to complete UPW intensively, which helped to establish trust and a collaborative approach to supervision.

Thoughtful placement allocation and support:

- Nabil was allocated a UPW placement at an Islamic Relief charity shop. This setting was culturally appropriate and aligned with his values, supporting a sense of belonging and dignity.

- The PP ensured the placement was sensitive to Nabil’s background, and provided consistent support throughout.

- Nabil engaged with Careers Wales and completed modules within the ETE programme. These sessions helped him build confidence and explore future employment opportunities.

Outcome: Nabil successfully completed all UPW hours in a timely manner. A completion letter was sent, praising his commitment and progress. Shortly after, Nabil secured paid employment, demonstrating the positive impact of inclusive, person-centred supervision. His experience at the charity shop also motivated him to pursue further voluntary work, strengthening his social capital and supporting long-term desistance.

Example of effectiveness: Supporting engagement through unpaid

work

Manish, a 43-year-old Indian man, received an SSO for a sexual offence. Although he maintained his innocence, he accepted the court’s decision and demonstrated motivation to engage with the Probation Service. His sentence included a multi-requirement order with RAR days, UPW, and notification requirements under the sex offender register.

Responsive allocation of UPW placement:

- A workshop placement was carefully selected to match Manish’s risk profile and needs. This ensured his safety and managed vulnerabilities linked to his status as a registered sex offender, while mitigating risks associated with community-based placements.

- Flexibility was built into the plan to accommodate Manish’s personal commitments, including caring responsibilities for his disabled wife.

- Although Manish had a professional background, he embraced the chance to learn new skills through his UPW placement. Paired with a carpenter, he gained practical experience and later shared examples of home projects that he had completed using those skills.

Outcome: Manish engaged consistently, completing all UPW hours without absence. His ETE sessions helped him to develop new skills. The case was well managed, with strong motivation and positive reinforcement, demonstrating how tailored, strengths-based approaches can enhance engagement and rehabilitation.

Statutory victim work (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Proactive work with the victim in a high-risk domestic abuse case

A 26-year-old man had committed a domestic abuse offence against his female partner, following multiple assaults that ended only when a neighbour intervened. The case was managed under MAPPA due to the severity of the offence and the risk posed.

Victim engagement and safety planning:

- The victim requested a non-contact condition and an exclusion zone (EZ), both of which were implemented.

- The victim liaison officer (VLO) proactively checked the EZ and made further enquiries to support a retrospective restraining order.

Multi-agency collaboration and support:

- The VLO coordinated with Women’s Aid, counselling services, and housing teams to implement target hardening measures.

- When the PP requested changes to the EZ, the VLO provided clear, reasonable explanations for maintaining the existing safety plan.

Direct engagement and advocacy:

- The VLO made face-to-face contact to explore the victim’s personal circumstances.

- They made significant efforts to offer additional support, including a MARAC referral, contact with housing services, and IDVA involvement.

- The VLO also explored children’s services involvement and identified family support needs.

Outcome: This case highlighted the importance of proactive, trauma-informed work with victims. The VLO’s persistence, multi-agency coordination, and safeguarding advocacy ensured the victim’s safety and dignity were prioritised throughout the supervision process.

Example of effectiveness: Improving victims’ safety through proactive contact and multi-agency collaboration

A 42-year-old man committed a prolonged violent assault against his female partner, including multiple physical attacks and attempted strangulation. The case was managed under MAPPA due to the severity of the offence and ongoing risk concerns.

Victim engagement and liaison:

- The VLO initially received no response to victim notification scheme letters and leaflets, so they made proactive efforts to engage the victim.

- The VLO contacted the victim by telephone to explain the process and offer support. They worked closely with the IDVA to ensure the victim’s needs were understood and prioritised.

Multi-agency coordination:

- The VLO actively participated in MAPPA reviews, where actions were agreed to support the victim’s safety, including suspension of contact.

- Actions were reviewed and confirmed with the IDVA, which ensured there was a joined-up approach to safeguarding.

- Housing arrangements were also considered, and police markers were added for extra protection.

Recall and exit planning:

- After the offender was recalled, the VLO ensured the victim was notified and that exit safety plans were reviewed and updated. This included coordinating with the police and housing services to maintain protective measures.

Outcome: The case demonstrated effective liaison with the victim through persistent engagement, trauma-informed communication, and multi-agency collaboration. The VLO’s role was central to ensuring that the victim’s safety and dignity were upheld throughout the supervision process.

Management oversight (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Structured management oversight to ensure continuity of risk management and decision-making

Scott, a 36-year-old Welsh man, was sentenced to custody for breaching an indefinite restraining order against his ex-partner. On release, he was placed on licence with conditions including GPS tagging, an exclusion zone, drug testing, and a no-contact clause. He had additional needs, including a brain injury and mobility issues. He spoke Welsh.

After his case entered Probation Reset, a new domestic abuse incident involving a different partner was reported via the reportable incidents scheme. This prompted a reassessment of his risk and management plan.

Proactive and responsive management oversight:

- The SPO maintained regular dialogue with the PP, offering both strategic direction and practical support.

- During PP absence, the SPO ensured continuity of risk management and led discussions about recall, considering alternatives such as integrated offender management and referral to an approved premises (AP).

- The SPO completed the AP referral and escalated police enquiries.

- They engaged directly with Scott to reinforce licence conditions and attended a three-way meeting with the PP and Scott, modelling collaborative supervision.

- Following recall, the SPO provided clear direction, advising Scott to surrender to the police after an unplanned office visit.

The SPO demonstrated active leadership and trauma-informed practice, going beyond procedural oversight to provide ethical and responsive risk management. Their direct engagement with Scott, consistent support of the PP, and clear decision-making exemplified visible leadership and shared responsibility in high-risk supervision, particularly for individuals with complex needs.

Example of effectiveness: Effective oversight in a high-risk, high-need case

Jules, a 28 year-old-woman with a mixed ethnic background, was sentenced to a CO following an offence of violence against an emergency worker. Her case presented multiple layers of complexity: she had a diagnosis of ADHD, struggled with alcohol misuse, and experienced ongoing mental health concerns. Jules was also vulnerable due to her involvement in sex work and her dual status as both a victim and perpetrator of domestic abuse.

- The PP acted proactively from the outset, initiating police and safeguarding checks and clarifying child protection concerns amid Jules’s chaotic circumstances, including homelessness and substance misuse.

- The SPO provided consistent oversight, offering both formal and informal support that enabled the PP to manage complex and evolving risks with confidence.

- When Jules’s risk escalated, the SPO and PP jointly reassessed her as very high risk. This triggered a timely MAPPA referral and MARAC involvement to ensure a coordinated multi-agency response.

- Despite breaches of the requirements on the CO, Jules remained engaged. The PP maintained a trauma-informed approach, while the SPO ensured that interventions were well-coordinated and risk management remained robust.

- The SPO played a central role in managing Jules’s case, ensuring coordinated interventions and robust risk management, despite repeated breaches of the alcohol treatment requirement. Their oversight supported trauma-informed practice, guided the PP’s decision-making, and upheld safeguarding and public protection. The SPO’s leadership maintained accountability and stability throughout the case.

References and acknowledgement (Back to top)

This Effective Practice Spotlight is based on information sourced while undertaking our inspection of the Wales Probation Service region. The manager responsible for this inspection programme is Simi O’Neill. Helen Amor, effective practice lead, has drawn out examples of effective practice from the inspection of the region. These are presented in this guide to support the continuous development of these areas in the probation region. We would like to thank all those who participated in any way during the inspection, and especially those who have contributed to this guide. Without their help and cooperation, the inspection and Effective Practice Spotlight would not have been possible.

Bradley, A. and Petrillo, M. (2022) Embedding Trauma-Informed Approaches in Adult Probation. University of Greenwich. Available at: https://gala.gre.ac.uk/id/eprint/43321 (Accessed 5 November 2025).

HM Inspectorate of Probation (2023) Issues, Challenges and Opportunities for Trauma-Informed Practice. Academic Insights 2023/10. Available at: https://hmiprobation.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk (Accessed 5 November 2025).

- Ministry of Justice. (2024) Multi-Agency Public Protection Arrangements (MAPPA) Annual Report: 2023 to 2024. London: HM Prison and Probation Service. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/multi-agency-public-protection-arrangements-mappa-annual-2023-to-2024 (Accessed 4 November 2025).

Phillips, J., Ainslie, S., Fowler, A., and Westaby, C. (2022). ‘“What Does Professional Curiosity Mean to You?”: An Exploration of Professional Curiosity in Probation’. British Journal of Social Work, 52 (1), pp. 554–572.

Pycroft, A. and Gough, D. (eds.), 2019. Multi-Agency Working in Criminal Justice: Theory, Policy and Practice. Second edition. Bristol: Policy Press.

Wainwright, J., Burke, L. & Collett, S. (2024) ‘A lack of cultural understanding and sometimes interest: Towards half a century of anti-racist policy, practice and strategy within probation’, Probation Journal, 71(2), pp. 116–138

Waring, S., Taylor, E., Giles, S., Almond, L. and Gidman, V. (2022) ‘Dare to Share’: Improving information sharing and risk assessment in multiteam systems managing offender probation. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, Article 869673. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.869673 (Accessed 4 November 2025).

Footnotes

[1] Domain 2 casework inspection refers to HM Inspectorate of Probation’s inspection framework that evaluates the quality of work with individuals under probation supervision. It focuses on case-level practice across key stages such as assessment, planning, implementation, and review. Inspectors examine whether work is personalised, analytical, and proportionate, addressing factors linked to offending, desistance, and public protection, while promoting engagement and rehabilitation.

[2] The learning organisation approach emphasises creating an environment where individuals and teams continuously acquire, share, and apply knowledge to improve practice. This approach recognises that performance is shaped by cognitive load, ergonomics, and organisational culture. By reducing unnecessary administrative tasks and supporting intuitive tools, organisations can minimise error, enhance decision-making, and enable practitioners to focus on high-value, person-centred work (https://infed.org/dir/welcome/the-learning-organization/).

[3] HM Inspectorate of Probation (2020). Supervision of service users – HM Inspectorate of Probation

[4] CAS3 (Community Accommodation Service Tier 3) offers up to 12 weeks of temporary housing for prison leavers at risk of homelessness, supporting safe reintegration from the first night of release. It is delivered through multi-agency coordination and is available across all probation regions in England and Wales. (Community Accommodation Service Tier 3 – guidance – GOV.UK).

[5] GRT communities in Wales are diverse ethnic groups with distinct cultures and histories. Despite longstanding roots in the region, they often face discrimination, limited access to services, and social exclusion. GRT communities are recognised under the Equality Act 2010. Their accommodation needs must be assessed and met by local authorities under the Housing (Wales) Act 2014 (for more information, see the Gypsies and Travellers Wales website).