Effective Practice Spotlight: The Probation Service – North East region

Effective practice methodology (Back to top)

Within the inspection of probation services across the North East, we assessed cases against HM Inspectorate of Probation service delivery standards. Inspectors considered whether practice in selected cases was sufficient to meet the engagement and desistance needs of people on probation, and whether activity was sufficient to keep other people safe.

The overall service delivery ratings were calculated based on the percentage of those cases that had been identified as sufficient against each of our key questions and standards.

HM Inspectorate of Probation’s definition of effective practice is ‘where we see our standards delivered well in practice’. Effective practice was seen within a number of cases inspected as part of fieldwork in the North East. This spotlight is designed to highlight where practice was effective.

North East effective practice summary (Back to top)

- Fieldwork took place in each North East probation delivery unit (PDU) between 28 April 2025 and 29 July 2025.

- We reviewed 292 cases, 185 of which were subject to a community sentence and 109 to release on licence.

- We also reviewed 204 court reports and 102 cases subject to resettlement provision.

- We inspected 31 unpaid work (UPW) cases and 29 statutory victim cases from across the region where community sentences and licences had started between 23 September and 29 November 2024.

- The strongest practice across most PDUs was found in the assessment and planning to reduce reoffending and support desistance. We also found the assessment and planning for engagement of the person on probation to be a strength in most PDUs. Two PDUs demonstrated strong engagement of the person on probation in their implementation and delivery.

- We found 74 pieces of effective practice within domain two casework.

- We found the most effective practice examples across multi-agency working, responsivity and engagement, interventions, and professional curiosity.

- In this spotlight report, we have highlighted the strongest examples of effective practice from the region and each PDU, across several themes related to organisational delivery and case management.

Our standards (Back to top)

These are the HM Inspectorate of Probation standards met by the examples of effective practice selected from across the North East region. A full list of our standards, plus further reading and research, can be found on our website.

- Regional leadership drives the delivery of a high-quality, personalised, and responsive service for people on probation.

- Assessment is well informed, analytical, and personalised, actively involving the person on probation.

- Planning is well informed, holistic, and personalised, actively involving the person on probation.

- Staff are enabled to deliver a high-quality, personalised, and responsive service for all people on probation.

- High-quality, well-focused, personalised, and coordinated services are delivered, engaging the person on probation.

Organisational arrangements and activity (Back to top)

The North East region demonstrated a commitment to delivering probation services, with organisational activity shaped by inspection findings, operational data, and practitioner insight. This ensured that policy and practice remained responsive to frontline realities. Below, we spotlight initiatives which highlighted how leadership and structure were driving improvement, reducing inefficiencies, and embedding effective practice across all PDUs.

Example of effectiveness: Back-to-Basics strategy

In response to staff feedback that they felt overwhelmed, despite largely manageable caseloads, the Regional Probation Director (RPD) commissioned, what she termed, a Back-to-Basics (B2B) initiative. This wide-scale review aimed to streamline practice by identifying non-essential tasks, inefficiencies, and opportunities for smarter working. The review team considered the tasks of frontline staff throughout the day and, where tasks fell outside of case management work, questioned why they were being done.

B2B was grounded in live operational data and staff feedback, ensuring that both quantitative insights and practitioner experience shaped decision-making. One PDU was chosen for this initiative, and the staff there identified the top 10 most cumbersome or over-bureaucratic processes which they felt took up time which could have been spent on case management. This dual lens revealed that a purely data-driven approach often missed the nuances of frontline practice.

A key tenet of B2B was that change must be staff led. Using lean methodology[1], staff groups identified inefficiencies and proposed practical solutions themselves. This approach:

- uncovered non-essential tasks unrelated to case management which were occurring daily

- highlighted essential tasks that could be done more efficiently

- identified gaps in learning and development, policy duplication, and bureaucratic waste

- considered cultural factors impacting practice

- ensured buy-in from staff, enabling them to influence change rather than reacting negatively to change imposed by senior managers

- focused the PDU’s efforts on improving key sentence management tasks, rather than those concerning performance counting, human resources, or other matters unrelated to sentence management

- improved the quality of practice and saved time.

Underpinned by an enabling and innovative senior leadership team, a key strength of the North East region was its high-performing senior probation officer (SPO) group, who were central to the B2B process. These SPOs were problem solvers, leading change, shaping improvements, and influencing regional strategy. Their involvement fostered a culture of trust, ownership, and innovation.

B2B bridged the gap between outdated policy assumptions and the realities currently faced by probation practitioners (PPs). For example, the first B2B pilot revealed a major discrepancy in the ‘home visit risk assessment` process. The timings in national policy were vastly different to the reality of the time taken to carry out those tasks. The pilot saved over 11,000 hours in the North East alone and led to a national policy change in January 2025, recognised by the Chief Probation Officer. The North East also applied the B2B approach in other areas of work, such as redundant non-statutory intervention processes, nDelius codes, management oversight, induction paperwork, and multi-agency public protection arrangements (MAPPA).

The B2B approach underpins the region’s continuous improvement strategy, supported by the head of performance and quality, and a newly appointed effective practice lead (EPL). As noted, this approach was recognised nationally by HM Prison and Probation Service, with the North East seen as leading the field for system-wide innovation.

Example of effectiveness: Effective practice strategy

In the latest inspection cycle, five out of seven PDUs in the North East received a ‘Requires improvement’ rating for planning and public protection work, making the region stand out for its strong grasp of planning and public protection, driven by its effective practice strategy.

Strategic leadership and governance

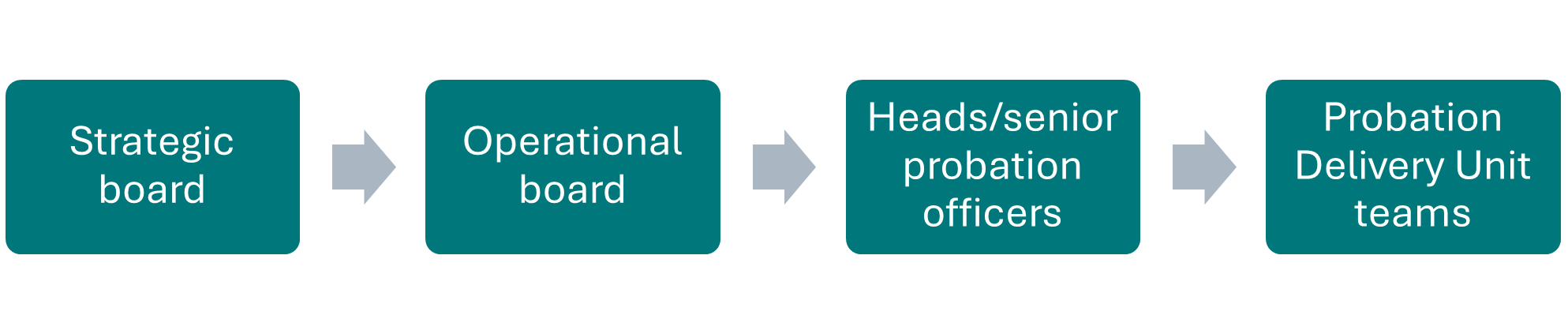

The North East strategy was led by a regional effective practice strategic board, supported by an effective practice operational board, chaired by the EPL, on a quarterly basis. These boards enabled the North East region to operate as one cohesive unit in supporting staff development as well as improving services and outcomes for people on probation.

Integral to this was the ‘continuous improvement database’, developed and maintained by the quality development team manager. This database was established as a tool to collate findings from a range of performance and quality sources and tracked quarterly and annual trends.

The sources of information that were drawn from included, but were not limited to: HM Inspectorate reports, deaths under supervision reviews, Serious Further Offence ‘early looks’/reviews, complaints, regional case audit tools/court case audit tools, as well as performance, assurance, and risk (PAR) audits. Once the data was gathered, the effective practice operations board determined themes and trends in relation to areas of good practice and areas for development. From these themes, the board devised a live learning document, called the ‘Improvement Quarterly’, which formed the basis for reflective discussions in team meetings, development days, or within everyday business as a proactive learning tool.

Additionally, the boards, alongside subject matter experts, collaboratively produced mandatory protected development day (PDD) materials, based on regional trends and strategic directives. These resources were not intended to take up the full PDD, allowing for the production of locally formed materials by business units to suit their needs. These included Understanding MAPPA and Collaborating with the Victim Liaison Unit.

Empowered staff network

The North East benefited from a strong, solution-focused staff group across all PDUs and business units. This staff group, mainly SPOs, attended the operational board and disseminated learning through a structured cascade model, embedding updates into team meetings.

This approach fostered ownership, influence, and consistency in practice development.

Training and impact

Since January 2024, the EPL and SPOs had delivered 38 interactive sessions to over 500 practitioners, focusing on risk assessment and risk planning. The training had been co-designed with the regional quality development and learning and development teams, as well as the head of public protection, using HM Inspectorate of Probation findings, case studies, videos, and multi-agency examples. There was now a rolling Professional Qualification in Probation (PQIP) and probation services officer risk workshop, as well as court and prisons variation.

PAR group scores improved from 69 per cent (2023), in relation to risk assessment and planning, to 81 per cent (2024), in relation to risk as a key line of enquiry, supported by co-facilitators in each PDU for ongoing consolidation.

Innovative commissioned work

The effective practice strategy was involved in some innovative commissioned work, including:

- Trauma recovery model (TRM) training via the TRM Academy, facilitated by Mr Jonny Matthews (consultant social Worker and criminologist), Dr Tricia Skuse (consultant clinical psychologist), and Mr Dusty Kennedy (TRM Academy Director). This training was commissioned as a direct response to the thematic inspection, The quality of services delivered to young adults in the probation service.

- A total of 22 mental health self-help guides were commissioned from Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne & Wear NHS Foundation Trust to support people on probation, victims, and staff who were experiencing mental health difficulties. These covered a wide range of topics (for example, managing anger, sleeping problems, anxiety) and were written by NHS clinical psychologists. To maximise engagement, they were also available in an easy read and audio format. Since their launch (in January 2025), the guides had had over 2,700 views with evaluation planned for October 2025.

- In collaboration with the Personality Disorder Project, Lads Like Us[2] was commissioned to deliver the impactful and unique The Million Pieces Experience on two occasions for staff; this highlighted how PPs can make a difference by simply asking why,and adopting a trauma-informed approach.

- A Trauma-Informed Intervention project is scheduled for delivery in collaboration with consultant clinical psychologist Dr Warren Larkin. The initiative will centre on a ‘train the trainer’ model to embed the principles of Dr Larkin’s Routine Enquiry about Adversity in Childhood (REACh) approach. This project aims to build capacity across the North East Region by supporting the implementation of trauma-informed practices and interventions within probation services.

Leadership development

- The Psychological Safety Ignite Workshop for Senior Leaders was planned for November 2025, aligning with the area executive director’s strategic objectives and reinforcing the role of leadership in cultural change.

The North East’s strategy was a dynamic, staff-led model that blended evidence, academia, innovation, and strong leadership. With a responsive EPL and strong PO network, the region was not only improving local quality, but also influencing national practice.

Example of effectiveness: Engaging people on probation

The North East region embedded engaging people on probation as a strategic priority, with four regional peer mentor coordinators and a lived-experience manager driving engagement across all PDUs. There was also a designated PDU head of function overseeing engaging people on probation, ensuring strong leadership and integration into operational delivery.

Accountability and impact

Engaging people on probation forums were held every 12 weeks in each of the PDUs, chaired by PDU heads and with a membership that included people on probation, the engaging people on probation team, and attendees from other functions, such as health and justice, and equity, diversity, inclusion and belonging, as and when required. Dedicated SPO champions drove participation and led on task and finish groups. The forum model ensured accountability and consistency, and offered tangible outcomes such as improved reception areas, redesigned letters, and more inclusive spaces.

Local innovation

- Sunderland PDU ran the region’s longest-standing forum and set a benchmark for innovation. Its successful quarterly World Café events[3] had led to the rollout of a sentence plan leaflet, an induction pack pilot, a neurodiversity interview room, lived-experience input in staff development, improved trauma-informed practice, and community reporting hubs.

- Newcastle PDU held well-attended quarterly forums, co-led by an SPO. Feedback shaped sentence planning tools and extended engagement post-sentence to reduce the ‘cliff edge’[4] effect. Collaboration with the West End Women and Girls Project enabled women-only reporting days in community hubs after the city centre office move.

- South Tyneside and Gateshead PDU had six active volunteers, current and recent probation clients, supporting forums, focus groups, and co-production. Forum representatives accessed peer mentor training via Commissioned Rehabilitative Services providers, strengthening engagement and employment pathways.

- Stockton and Hartlepool PDU involved people on probation and volunteers in securing the Enabling Environments Award.[5] Forums were well structured, with ongoing work focused on young adults and regular peer mentor support in the office.

- County Durham and Darlington PDU showcased impressive forum activity. Attendees included individuals who had completed or were undertaking peer mentor training, and some who had benefited from peer support. The PDU had streamlined the induction pack from 28 to 12 pages, with simplified language co-designed by the forum. Members were visibly proud of their contribution.

- Redcar, Middlesbrough and Cleveland PDU had made quick progress in engaging people on probation. They collaborated with Cleveland’s violence reduction unit to embed lived experience in their work.

- Northumberland and North Tyneside PDU had implemented the sentence plan leaflet and celebrated lived experience at their recent award ceremony. A rural subgroup had been introduced to support participation from those facing travel barriers, with virtual engagement options available for those in remote areas or employment.

You can read more about the Enabling Environments values and standards awarded in Stockton and Hartlepool, and the staff-led award ceremony in Northumberland and North Tyneside in our Effective practice guide – Recruitment, Training and Retention.

Inclusive and responsive practice

Forums across the region actively reviewed protected characteristics, to identify under-represented voices and guide targeted outreach. Topics were led by feedback, rather than assumptions, and included areas such as reception experience, addiction support, and exit planning. Positive practice was also shared, to promote consistency.

Integration and influence

Engaging people on probation was embedded in PQiP training and quarterly reviews with UPW and women’s teams. The region contributed to national engaging people on probation events and policy development, with lived experience shaping both local and wider practice.

The North East’s engaging people on probation strategy was a staff-led, lived experience-informed model that drove meaningful engagement and service improvement. With strong leadership, structured processes, and full regional involvement, engaging people on probation was embedded as a culture, and was delivering real impact across the region.

Case management (Back to top)

HM Inspectorate of Probation inspection activity focuses on the quality of case supervision, including assessment, planning, implementation, and review, as defined by the ASPIRE model. This section highlights effective practice in delivering personalised, risk-informed, and desistance-focused supervision. Beginning with court work, we explore how PPs across the North East region have applied professional curiosity, trauma-informed approaches, and multi-agency coordination to support sentencing decisions and post-sentence engagement. Each example reflects how organisational arrangements and practitioner skill have contributed to safer outcomes and improved rehabilitation.

Court work (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Use of maturity screening tool at pre-sentence report (PSR) stage

June, a 24-year-old woman, was convicted of possession with intent to supply cannabis. This was her first conviction. She was a victim of domestic abuse (DA) in the context of the offence, and at the time that the PSR was written she was residing in a women’s refuge.

Consideration of maturity and vulnerability:

- The PSR effectively applied the maturity screening tool, identifying case-specific maturity-related factors.

- The PSR reflected on the timing of the offence, noting maturity relevance at the from the outset.

- Maturity was considered in the context of experience in a DA relationship, including vulnerability and coercion.

- The PSR was clear and analytical, offering the court insight into the impact of trauma, maturity, and mental health.

Outcome: Custody was considered, but the court was informed by the PSR and accepted the recommendations, imposing a 12-month community order with rehabilitative activity requirement (RAR) days.

Example of effectiveness: Public protection through effective (PSR)

Gary, a 22-year-old man, received a suspended sentence order (SSO) with an alcohol abstinence monitoring requirement (AAMR) and RAR days for racially aggravated violence. The case involved complex factors, including maturity, trauma, and a hostile orientation. Risk concerns included DA, safeguarding, public protection, self-harm, and threats to staff and associates. MAPPA was engaged during remand, as a result of credible threats against custody staff.

Person-centred assessment:

- The PSR disclosed childhood experiences using person-centred language, avoiding any triggering terms, such as ‘trauma’.

- Vulnerability concerns identified during interview led to prompt contact with safer custody staff.

- A wide range of sources informed the assessment, supporting the very high risk of serious harm classification; these included youth justice service (YJS) records, custody reports, and MAPPA input.

- The PSR author compared current and past PSRs, noting a pattern of early motivation followed by poor engagement, critical for informing realistic sentencing and supervision planning.

Outcome: The PSR was key in shaping the court’s understanding of Gary’s risks and needs, demonstrating how high-quality reporting can influence sentencing and risk management in complex cases. Its depth and sensitivity ensured that safeguarding concerns were addressed, and appropriate interventions initiated early.

The ASPIRE model of case supervision (Back to top)

‘Contemporary probation practice is based upon the ASPIRE model of case supervision. In our core inspections, we judge the quality of delivery in individual cases against this model’[6]

The four standards for the inspection of adult case supervision follow the ASPIRE model by focusing on the quality of assessment, planning, implementation, and review. Within each standard, we assess the quality of engagement, work to address desistance, and work to keep other people safe.

In the case example below, we saw evidence of effective practice across all elements of the ASPIRE model. Each example highlights effective practice in key areas such as risk assessment, trauma-informed engagement, multi-agency collaboration, and desistance-focused interventions.

Example of effectiveness: Addressing substance misuse and reoffending through integrated support

John, a 48-year-old man, was subject to a custodial sentence for burglary offences. He had a significant offending history linked to substance misuse and acquisitive offending.

Strong resettlement assessment and planning:

- Resettlement planning was informed by thorough information exchange between the PP, prison offender manager, and relevant agencies.

- Family input, including from a dependant, informed the home detention curfew (HDC) assessment and supported decision-making concerning release.

- The assessment identified desistance needs and included contingency plans to manage potential risks, particularly in relation to substance misuse and contact with children.

Appropriate interventions:

- Community Accommodation Service 2 housing and support services, including a housing support worker and substance misuse treatment, were arranged for the day of release.

- Home visits were conducted separately by the PP and National Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders (NACRO), and drug testing was carried out routinely.

- The PP responded to drug use on licence with a compliance letter, followed by a referral to substance misuse services for additional recovery support, and later to the integrated offender management programme, which was accepted.

Review of progress:

- Progress was reviewed continuously throughout the order.

- The sentence plan was adapted in response to emerging needs, particularly in relation to dependency and recovery.

- Agencies worked collaboratively, sharing information regularly. NACRO’s progress review documents were especially valuable, capturing goals that John had achieved, such as claiming benefits, obtaining identification, and registering with a general practitioner (GP), through effective engagement with housing support.

Outcome: The coordinated, responsive approach ensured that John’s resettlement needs were prioritised. The use of the ASPIRE model was evident in the holistic support provided. The overall planning and delivery were robust, with clear evidence of risk management, recovery-focused intervention, and multi-agency collaboration.

Example of effectiveness: Collaborative assessment and planning promoting engagement

Sam, a 22-year-old man, received an SSO for a violent offence, with AAMR, an accredited programme, and RAR days.

Comprehensive risk assessment:

- Use of multiple sources, including formal assessments, YJS records, and interviews.

- Professional curiosity was evident in exploring risk factors.

- Self-assessment identified attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, and binge drinking as concerns and potential barriers to engagement.

- Employment and accommodation were noted as protective factors.

Collaborative and responsive planning:

- Planning proactively addressed emotional wellbeing, ADHD, and maturity.

- Objectives were sequenced with Sam’s input, supporting engagement and motivation.

Safeguarding and multi-agency coordination:

- Prioritisation of public protection through police and safeguarding enquiries.

- MAPPA involvement and management oversight were clearly documented.

Outcome: The PP built a strong working relationship with Sam, enabling effective risk monitoring. Sam completed both the accredited programme and AAMR, with continued learning supported through one-to-one toolkits during RAR days.

Professional curiosity (Back to top)

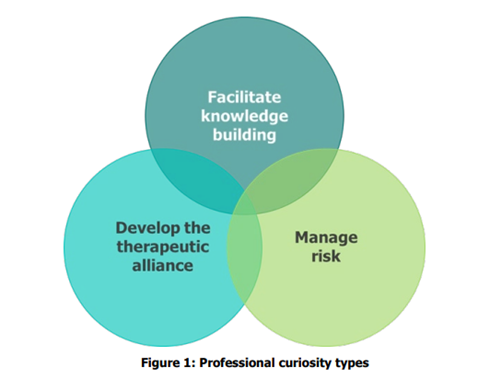

Professional curiosity is essential to effective probation practice (see Figure 1). It involves proactive questioning, critical thinking, and reflection to understand an individual’s circumstances fully. By looking beyond surface-level information and challenging assumptions, practitioners can better identify hidden risks and needs. This approach is especially important in safeguarding, where missed signs can lead to poor outcomes. HM Inspectorate of Probation highlights that a culture of curiosity, supported by supervision, open dialogue, and awareness of bias, enhances case supervision and decision-making.

The research of Phillips et al. (2022)[7] with probation professionals identified that practitioners’ understanding of professional curiosity fell into four broad categories:

- risk focused

- therapeutic

- knowledge building (improving the practitioner’s own knowledge)

- neutral (being generally questioning, ‘nosiness’).

While professional curiosity is often associated with assessing risk, its value extends far beyond this. Practitioners are encouraged to adopt a broader perspective, using curiosity as a therapeutic tool to build trust, explore individuals’ lives in depth, and support their own continuing professional development.

In the case examples below, we saw how professional curiosity underpinned effective, person-centred probation practice, enabling practitioners to uncover hidden risks, respond to complex needs, and tailor supervision to individual circumstances.

Example of effectiveness: Professional curiosity in assessment and planning

Vicky, a 25-year-old woman, was released on HDC after a long custodial sentence for a DA offence against her partner, resulting in serious injury. She had a history of DA as both victim and perpetrator, with diagnoses of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and dissociation. Concerns emerged when she failed to disclose a renewed relationship with the victim, who also poses a risk to children.

Professional curiosity in practice:

- Risk management included exclusion zone and restraining order.

- There was robust, holistic planning, with ongoing reassessment of harm and affected individuals.

- The PP showed strong professional curiosity, regularly analysing police and safeguarding data.

- The PP proactively gathered intelligence from a wide network, including the ex-partner’s probation officer, management of sexual offenders and violent offenders, and children’s social care (CSC) services.

Accommodation and safeguarding:

- The PP was persistent in securing safe housing, swiftly assessing addresses and potential victim impact.

- Safeguarding actions were timely and proactive.

Support and rehabilitation:

- Referral to the engaging people on probation team supported protective factors from custody, including group work and community ties.

- Planning was thorough, objective-led, and addressed key criminogenic needs.

Outcome: The PP demonstrated strong professional curiosity, taking a holistic approach to risk assessment by verifying information beyond standard DA and safeguarding enquiries, including risks to Vicky and others, particularly children.

Example of effectiveness: Professional curiosity and cultural responsivity in practice

Kai, a 33-year-old British Asian man of Bangladeshi heritage, received a long custodial sentence for a weapon-enabled robbery. Safeguarding enquiries revealed historic DA concerns which were also linked to a child. On release, he was subject to multiple licence conditions, including residence at an approved premises (AP), Thinking Skills Programme (TSP) participation, and non-contact restrictions. He was managed under MAPPA Category 2, Level 1. He was a practising Muslim, and experienced anxiety and panic attacks.

Engagement and relationship building:

- The PP built a strong, consistent rapport with Kai throughout supervision, establishing clear boundaries through open, respectful dialogue.

Cultural and religious responsivity:

- Demonstrating professional curiosity, the PP explored cultural and religious identity with sensitivity, using appropriate challenge to deepen understanding.

- The PP supported religious observance, including Eid and Ramadan.

- Appointments were scheduled around prayer commitments, avoiding Fridays.

Risk and safeguarding:

- The PP conducted regular police and safeguarding enquiries, addressing concerns directly.

- Boundaries were clearly established through open, in-depth conversations, fostering a safe and respectful working relationship.

- Interventions tackled DA, including views on arranged marriage.

Flexible, safe practice:

- The PP responsively reviewed the exclusion zone to enable mosque attendance, with senior oversight to ensure victim safety.

Outcome: The PP took a responsive, culturally informed, and tailored approach, demonstrating strong professional curiosity through thorough information gathering, collaborative work with other agencies, and high-quality risk discussions with managers.

Example of effectiveness: Professional curiosity, proactive engagement, and tailored support

Gordon, a 53-year-old man, was convicted of harassment in a DA context and sentenced to a community order (CO) with RAR days. He had a history of intimate partner violence, linked to alcohol dependency and job loss. He had diagnoses of mild epilepsy, dyslexia, and PTSD. Shortly after sentencing, he entered a residential rehabilitation centre for alcohol dependency.

Professional curiosity by PP:

- The PP regularly contacted the rehabilitation centre to confirm his whereabouts with staff.

- A home visit to the unit was swiftly completed, despite it being out of area.

- Contact was made with the staff involved and it was agreed that he could be permitted fortnightly telephone contact with his PP while he was in the residential rehabilitation centre.

- Decisions regarding contact were endorsed by an SPO.

Outcome: Gordon reported abstinence and engaged well with alcohol services. The PP amended the restraining order to allow solicitor contact for divorce proceedings, and there was less rumination over the victim of the offence.

Resettlement (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Coordinated communication to support transition to the community

Oscar, a 27-year-old man, was released immediately following sentencing for a violent offence involving a weapon because of time served on remand. Limited pre-release planning was possible. He had a diagnosis of psychosis and was prescribed medication. Historical concerns included DA and previous youth justice involvement for sexual offences.

Communication and coordination:

- The PP demonstrated proactive and coordinated practice to support Oscar’s transition into the community.

Multi-agency engagement:

- Regular contact was maintained with key agencies (for example, prison staff, mental health services, GP, CSC services), using varied communication methods to coordinate support.

- Post-release follow-up addressed information gaps and facilitated access to ongoing care.

Responsive practice in risk and engagement:

- Non-engagement prompted use of professional curiosity and known contacts to re-establish supervision.

- Supervision sessions reinforced appointment attendance and the importance of engagement.

- Safeguarding updates were shared with relevant agencies to support risk management.

Outcome: Despite an unplanned release and initial non-compliance, proactive communication and multi-agency coordination enabled access to mental health support and re-engagement with probation services.

Example of effectiveness: Pre-release communication and planning to support engagement post-release

Karl, a 29-year-old man, received a custodial sentence for sexual offences against a woman. He targeted a vulnerable individual and demonstrated predatory behaviours.

Proactive engagement:

- The PP maintained consistent contact over seven months pre-release, using video-link and email, and liaising with key family members, including his wife.

- Efforts were made to build trust, acknowledging past negative experiences with professionals.

- Strong collaboration was maintained with the wider professional network.

Planned post-release risk management:

- An offender personality disorder (OPD) formulation was completed pre-release, enabling immediate delivery of intensive intervention and risk management services (IIRMSs) at the AP.

- IIRMSs focused on psycho-educational work targeting thinking patterns, behaviours, and harm reduction.

- Two MAPPA Level 1 reviews were conducted during the pre-release period.

- The PP actively promoted inter-agency collaboration, including CSC service involvement in sexual risk assessment.

Outcome: This committed approach encouraged positive engagement with the AP, partners, and PP post-release.

Public protection (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Effective risk management and disclosure

Riley, a 39-year-old man, subject to an SSO with RAR days, UPW, and the Building Better Relationships (BBR) programme following DA-related offences against his ex-partner and son. This case required a strong focus on public protection and safeguarding.

Assessment and risk understanding:

- The risk to others assessment was robust and accurate.

- Relevant DA and safeguarding enquiries were made and used to inform the risk assessment.

- The PP demonstrated a clear understanding of the nature and imminence of risk, including coercive control, jealousy, and entitlement, which supported later planning to safeguard known adults and children.

Planning and risk management:

- Planning effectively safeguarded children, the ex-partner, and the current partner. The risk management plan (RMP) struck a balance between control measures and rehabilitative support. Key features included:

- disclosure to the new partner

- completion of the BBR programme

- inclusion of other professionals, such as CSC staff and the DA safety officer (DASO).

- BBR started promptly, supported by positive pre-programme work and liaison with the DASO working with the victim of the index offence.

Disclosure:

- Risks to children, ex-partner, and current partner were actively managed.

- Disclosure to a new partner was handled effectively, with consent obtained for contact and open communication encouraged.

- The partner’s understanding of the individual’s criminal history was explored and found to be accurate, indicating transparency.

- The PP explained the Clare’s Law disclosure scheme and signposted the partner to relevant support services. This was done without breaching confidentiality and was well documented in case notes, evidencing sound decision-making.

Outcome: The PP’s proactive and transparent approach to safeguarding, combined with multi-agency collaboration, ensured that public protection remained central throughout.

Example of effectiveness: Risk management despite non-engagement

Daniel, a 33-year-old man, received a CO with RAR days following a conviction for making threats to kill. The PSR identified that Daniel’s mental health complex needs might exceed the capacity of probation services. He disengaged early because of severe mental health instability, resulting in multiple arrests, two Mental Health Act detentions, and eventual remand for similar offences.

Risk management:

- There was persistent multi-agency coordination, involving regular communication and collaboration with the community psychiatric nurse, social worker, and family members.

- There was active participation in care planning, including attendance at mental health review meetings and safeguarding discussions.

- There was ongoing risk monitoring, through regular police and safeguarding enquiries, and continuous updates from involved professionals to track Daniel’s whereabouts and mental health status.

Continued attempts to engage during remand:

- Solo and joint prison visits were conducted, video-links were used, and referrals were made to relevant custodial services.

- Emerging risk concerns were shared with safer custody teams, the prison key worker, and the police, to ensure coordinated risk management.

Information sharing for PSR:

- Close collaboration with the PSR author contributed to detailed information sharing to support a recommendation for a hospital order, given the ongoing mental health deterioration.

Outcome: This case highlighted how persistent, coordinated multi-agency working and proactive risk management can help to protect the public, even when direct engagement with the individual is not possible. Daniel’s severe mental health instability ultimately led to multiple Mental Health Act detentions and remand, following further threats to kill. Nonetheless, the PP’s commitment to safeguarding and inter-agency collaboration ensured that risk was continually assessed and managed.

Multi-agency working (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Managing risk through multi-agency support

Julie, a 23-year-old woman, received an SSO with RAR days for violent offences, committed while subject to a CO. She had a history of non-compliance and was identified as both a perpetrator and victim of DA.

Assessment and risk management:

- Assessment was informed by multi-agency input, highlighting a motivation to engage and protective factors, including support from recovery and DA services.

- Key drivers of offending, substance misuse, and homelessness were identified, with active support in place.

- Risk analysis was strengthened through DA enquiries, police intelligence, multi-disciplinary team meetings, and professional discussions.

- Safety planning included supported accommodation and a restraining order against an ex-partner.

Engagement and enforcement:

- While enforcement letters were issued for missed appointments, flexibility was shown to support engagement.

- Persistent non-compliance led to consideration of compliance meetings, SPO warnings, and potential SSO activation.

- Home visits and outreach were used to maintain contact and encourage engagement.

Outcome: A coordinated, multi-agency approach enabled timely information sharing and action. Julie was moved to a refuge, referred to emotional wellbeing services, and engaged with support. OPD pathway consultation and community mental health involvement were also pursued.

Example of effectiveness: Multi-agency information sharing and joint working

Tom, a 39-year-old man, received an SSO with RAR days and an alcohol treatment requirement (ATR) for sexual offences. He had a history of DA, prior involvement with CSC services, and was a veteran diagnosed with PTSD. He was alcohol dependent and reported some substance misuse.

Partnership working during assessment and planning:

- Personal circumstances, including living arrangements, relationships, lifestyle, and social networks, were explored to inform risk assessment and sentence planning.

- Partner agencies were effectively engaged, with clear communication regarding arrest details, safeguarding concerns, DA disclosures, and any relevant restrictions.

- Positive efforts were made to engage Tom, including assessment of support networks and capacity to comply with the sentence.

- The RMP clearly outlined agency roles, control measures, and restrictions.

- Evidence of joint planning and active monitoring was seen across key areas such as living arrangements, relationships, restrictions, and compliance.

- A MAPPA referral was completed, in line with risk management protocols.

Appropriate interventions:

- CRS were used effectively, with meaningful contributions from workers in dependency and recovery, personal wellbeing, and education, training, and employment (ETE).

- The PP worked collaboratively with the police, including a joint appointment to explain sexual offender registration requirements and sentence expectations.

- GP and mental health interventions were reviewed in a joint meeting with dependency and recovery services, ensuring a coordinated approach to support.

Outcome: Key risks were comprehensively assessed with partner agency input, leading to targeted interventions. Collaborative work with the police and recovery services provided clear guidance and supported engagement. Tom completed emotional awareness modules, Level 2 qualifications in mathematics and English, a Microsoft Word course, a relationships programme, and work on sexual preoccupation.

Engagement and responsivity (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Strengths-based and responsive case management

Paul, a 31-year-old man, was sentenced to a CO with RAR days for a drug-related offence. He had diagnosed mental health conditions and dyslexia, and there was a pattern of DA in his relationships.

Engagement in assessment:

- Active engagement was demonstrated during the assessment process, with personal circumstances and individual needs considered.

- Risk assessments were clearly explained, including expectations and the consequences of non-compliance.

Responsive practice:

- Regular text reminders were used to support disclosed memory difficulties and ADHD, enhancing his ability to engage.

- Appointments were scheduled in the afternoon, to accommodate his employment, demonstrating a flexible and person-centred approach.

Multi-source information gathering:

- Assessment was informed by a wide range of sources, including police and safeguarding enquiries, employment details, ATR assessment, home visits, and historic YJS records.

Needs-led planning:

- Planning addressed self-identified needs such as finances, relationships, and mental health, while also targeting key offending-related factors and building on his strengths.

Maintaining boundaries:

- The PP demonstrated flexibility while maintaining risk-based boundaries, such as limiting the number of consecutive telephone appointments to ensure meaningful engagement.

Risk management and oversight:

- Case management included regular oversight, with appropriate escalation of risk.

- Weekly contact was maintained in response to Paul’s risk level and disclosure of a new relationship.

Outcome: Responsivity and flexibility were demonstrated while maintaining clear boundaries. Case records were thorough, with ongoing engagement and transparent discussions around risk review and partner agency involvement. Compliance was regularly addressed, ensuring that Paul fully understood the breach process and the rationale behind any enforcement actions.

Accredited programmes and toolkits (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Tailored maturity intervention for a young adult, promoting engagement and insight

Stephen, a 19-year-old man, was sentenced to custody for a racially motivated violent offence, his first recorded conviction. Diagnosed physical and neurodivergent needs prompted consideration of how these might affect engagement with interventions.

Effective intervention approach:

- A maturity-focused intervention was delivered, using the Choices and Changes toolkit.

- Sessions began at an appropriate stage in the sentence and were consistently delivered.

- Content was tailored to address specific needs, including self-identity, building resilience to peer influences, discriminatory beliefs, and a focus on the role of social media within this.

- To enhance relevance and engagement, contemporary rap music was used to open discussions, which proved effective in securing active participation.

Ongoing review

- The PP conducted regular assessments of engagement. When concentration difficulties, potentially linked to ADHD, were observed, a fidget toy was introduced in subsequent sessions. This simple adaptation led to improved focus and richer discussions.

Outcome: Engagement increased over time, with tailored and responsive approaches supporting insight development.

Example of effectiveness: Effective practice to achieve programme delivery

Gary, a 24-year-old man, was subject to a CO with a requirement to complete TSP when he committed further offences of shoplifting. The existing CO was revoked, and he was resentenced to an SSO, with a requirement also to attend TSP.

Flexible programme delivery and responsivity:

- While no diversity needs were disclosed, the PP remained mindful of a potential undiagnosed learning disability throughout.

- A practical approach was taken to complete TSP, acknowledging prior partial completion under a previous CO.

- The PP liaised proactively with the TSP manager, to resume this programme under the SSO, focusing on outstanding modules only.

- Prior progress on TSP was acknowledged.

- Several catch-up sessions were offered to support re-engagement.

Outcome: Gary was restarted on a new group, achieving successful and timely completion of the programme.

Statutory victim work (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Effective victim work in a high-risk DA case

A 28-year-old man committed offences of violence, stalking, harassment, and possession of a bladed article against his ex-partner. The perpetrator received a 21-month custodial sentence and was made subject to a restraining order.

Victim liaison and support:

- An initial contact letter was sent promptly, followed by telephone contact, in line with the victim’s preferred communication methods.

- The restraining order was explained to the victim, who had not received a copy. Additional advice and court contact details were provided.

- Efforts to explain the victim contact scheme and available support agencies were well documented.

- The victim’s concerns were clearly noted and shared with the PP, including discussions about exclusion zones and no-contact conditions.

- The victim was kept informed of licence conditions and release arrangements, with any changes communicated in a timely and clear manner.

Multi-agency coordination:

- The victim liaison officer (VLO) responded effectively to requests for support, escalating housing moves on safety grounds, and liaising directly with relevant agencies.

- Safety planning included consideration of family support and police involvement.

- When a change in PP occurred, the VLO ensured that all relevant information was passed on to the new practitioner and AP staff.

- This case demonstrated strong victim engagement, timely and responsive communication, and effective multi-agency coordination. The VLO played a key role in advocating for the victim’s safety and ensuring continuity of support.

Unpaid work (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Effective, safe, and tailored delivery of UPW for a pregnant woman

Emily, a 28-year-old woman, was sentenced to a CO with UPW for fraud offences. She had no antecedent history, and there were no DA or safeguarding concerns. At the time of sentencing, Emily was pregnant, which was a notable feature in the planning and delivery of her UPW requirement.

Court work and assessment:

- The report was well evidenced, drawing on police and DA enquiries, and captured her voice.

- Importantly, the report author liaised with the UPW team prior to sentencing, to ensure that her pregnancy could be accommodated through light duties and/or ETE sessions.

Tailored UPW delivery:

- Emily was allocated to an individual placement with light duties, supported by external pregnancy-related risk assessments.

- As the pregnancy progressed, she was offered independent work sessions, including making hats for a local community group.

- The induction onto UPW as well as her pregnancy were consistently factored into planning and delivery. The UPW team engaged sufficiently to ensure that safe and meaningful work was provided throughout.

Outcome: Emily completed her UPW hours promptly, with no enforcement or compliance issues, through a combination of individual placement, independent work, and ETE sessions (accounting for three per cent of her total hours). Her pregnancy was appropriately considered in allocation, risk assessment, and delivery.

References and acknowledgement (Back to top)

This Effective Practice Spotlight is based on information sourced while undertaking our inspection of the Probation Service – North East region. The manager responsible for this inspection programme was Dave Argument. Helen Amor, effective practice lead, has drawn out examples of effective practice from the inspection of the region. These are presented in this guide to support the continuous development of these areas in the probation region. We would like to thank all those who participated in any way during the inspection, and especially those who have contributed to this guide. Without their help and cooperation, the inspection and Effective Practice Spotlight would not have been possible.

[1] A systematic approach to improving efficiency and eliminating waste in processes by focusing on value creation for the customer, continuous improvement, and respect for people.

[2] Lads Like Us is a trauma-informed training organisation founded by lived experience practitioners in Manchester.

[3] World Café is a structured conversational process that brings together diverse participants in small rotating groups to explore key questions. It encourages collaborative dialogue, active listening, and idea-sharing, often resulting in co-produced insights and practical solutions.

[4] Cliff edge: A sudden and often detrimental withdrawal or reduction of support services, such as housing, mental health care, or financial assistance, typically occurring at a transition point (e.g. release from custody or end of a programme), which can leave women vulnerable to harm, reoffending, or relapse.

[5] Enabling Environments is a quality mark awarded by the Royal College of Psychiatrists to settings that promote psychological safety, inclusion, and wellbeing. It recognises environments where positive relationships, mutual respect, and personal growth are actively supported.

[6] HM Inspectorate of Probation. (2020). Supervision of service users. Available at https://hmiprobation.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/our-research/evidence-base-probation-service/supervision-of-service-users/

[7] Phillips, J., Ainslie, S., Fowler, A., Westaby, C. (2022). ‘”What Does Professional Curiosity Mean to You?”: An Exploration of Professional Curiosity in Probation’. British Journal of Social Work, 52(1), pp. 554–572. Available at https://academic.oup.com/bjsw/article-abstract/52/1/554/6134870?redirectedFrom=fulltext