The effectiveness of diverting children from the criminal justice system: meeting needs, ensuring safety, and preventing reoffending

An inspection by HM Inspectorate of Probation and HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services

Foreword (Back to top)

Youth out-of-court disposals (OoCDs) are alternatives to formal prosecution for children and are designed to divert them away from the criminal justice system by addressing their behaviour early and offering support to prevent further offending.

We last inspected this topic in 2018. Since then, there has been a substantial and sustained increase in the use of OoCDs for children, alongside a notable shift in the types of disposals being issued. The profile of children receiving OoCDs has also changed. Many now present with more complex needs and have had repeated contact with services such as the police and children’s social care. However, the system has not kept pace with these changes, and many children require a more tailored and intensive approach than is currently being delivered.

Evidence of the impact and cost effectiveness of OoCDs remains limited. National data is lacking, and there is little understanding of the number issued, how they are used, or how effective different approaches are. This gap remains despite our 2018 recommendation to include youth community resolutions in reoffending statistics and to evaluate their impact.

In the absence of a clear and consistent national framework, local areas have adopted varied approaches to diverting children from the criminal justice system, resulting in a ‘postcode lottery’ and raising concerns about fairness and public confidence.

Policing practices require greater consistency and oversight. An increasing number of children, including those involved in serious or repeat offending, were being dealt with informally, often by police alone. Where decisions were made jointly with youth justice services, roles and responsibilities were often unclear. The reasons behind decisions were not always recorded, making it difficult to understand how some outcomes were reached, and whether they were appropriate.

Effective diversion relies on strong partnerships, but many services are under strain due to limited resources and rising demand. As a result, it is harder to qualify for support, waiting lists are longer, and getting help in good time is more difficult. We found that many children struggled to get the support they needed, including education and mental health, and these needs often went unmet by the end of the OoCD process. Without coordinated and timely intervention, we found that children on the edge of the justice system were more likely to face further problems and become more deeply involved in offending.

Youth justice partnership boards did not have a clear understanding of the overall volume of OoCDs in their area or the effectiveness of interventions involving the youth justice service and other partners. The short-term and uncertain nature of some funding also makes it difficult for agencies to plan for the future.

Our case inspections highlighted the need for greater emphasis on safeguarding – both of the child and the public. Victims’ voices, especially those of child victims, must also be better heard and respected. Despite these challenges, there is much to build on. We observed committed staff using creative and effective approaches to engage children and families.

While there is widespread agreement on the importance of avoiding unnecessary criminalisation and promoting child-centred justice, we found that the current system is fragmented and inconsistent. This report highlights the pressing need for stronger governance, clearer guidance, and more consistent practice in the use of OoCDs for children. Our recommendations, if implemented, are intended to achieve these aims.

| Martin Jones CBE | Michelle Skeer OBE QPM |

| HM Chief Inspector of Probation | HM Inspector of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services |

Contextual facts (Back to top)

| 13,868 | The number of children cautioned or sentenced in 2024. This is virtually unchanged from 2023 but down 67 per cent from 2014. | |

| 21.7% | The proven reoffending rate over 12 months for children receiving youth cautions and youth conditional cautions (year ending June 2023). | |

| 58.5 % | The proven reoffending rate over 12 months for children receiving a youth rehabilitation order (YRO) (year ending June 2023). | |

| Not known | The number of children receiving an Outcome 8, 20, 21, 22 since 2012. | |

| Not known | The rate of reoffending of children who have received an Outcome 8, 20, 21, 22 since 2012. | |

| Not known | Number of children who received an informal disposal for the first time since 2012. | |

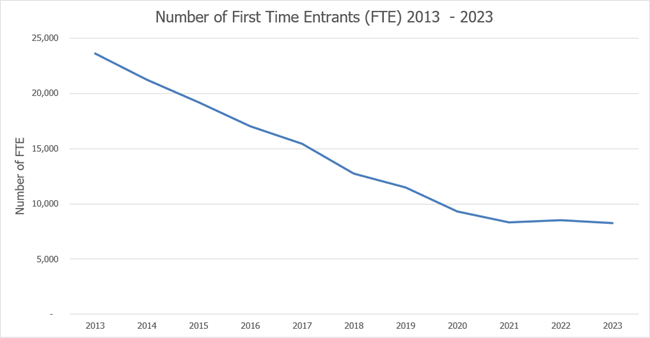

| 8,278 | The number of first-time entrants to the criminal justice system in the year ending December 2023. This is down 3 per cent from the previous year and 65 per cent from 2013. First-time entrant figures do not include children who have received community resolutions or Outcome 20, 21, and 22. | |

| 65% | Drop in first-time entrants between 2013 and 2023. | |

| 8,278 | The number of first-time entrants to the criminal justice system in the year ending December 2023. This is down 3 per cent from the previous year and 65 per cent from 2013. First-time entrant figures do not include children who have received community resolutions or Outcome 20, 21, and 22. |

| 65% | Drop in first-time entrants between 2013 and 2023. |

The graph below shows the reduction in the number of children entering the formal youth justice system[1] over a ten-year period.

What is a youth out-of-court disposal? (Back to top)

In England and Wales, youth out-of-court disposals. are alternatives to formal prosecution for children (under 18) who commit criminal offences. These are designed to divert young people away from the criminal justice system while still addressing their behaviour and providing support.

In this report we have used the term OoCD instead of Out-of-Court Resolution. In 2023, the NPCC updated this terminology in the adult framework. At the time of our inspection, this change had not yet been applied to the children’s framework.

Common types of youth out-of-court disposals

- An informal agreement between the police, the child, and sometimes the victim.

- The child must admit or accept responsibility for offending behaviour.

- Often used for low-level offences.

Community resolution (CR)

Youth caution

- A formal warning given by the police.

- Requires the young person to admit the offence.

- Recorded on the Police National Computer but not a criminal conviction.

Youth conditional caution (YCC)

- A formal caution with conditions attached (e.g., attending a programme, making reparations).

- Requires an admission of guilt.

- Non-compliance can lead to prosecution.

Outcome 22 – no further action (NFA)

- Used when the police decide not to pursue a formal charge or caution.

- No admission of guilt or acceptance of responsibility is needed.

- The child may be referred to the youth justice service (YJS) for joint decision-making.

Outcome 22 – deferred youth caution

- A final decision to issue a youth caution, delayed to allow the child to complete specified conditions (e.g., intervention work, reparative actions).

- If the young person successfully completes the conditions, the caution may not be formally recorded.

- Requires an admission of guilt.

- Non-compliance may lead to the caution being formally issued or alternative action taken (e.g., prosecution).

Outcome 22 – deferred prosecution

- Prosecution is paused while the child undertakes agreed activities for a specified period.

- No admission of guilt is needed but the case must meet the evidential standard for charge.

- If conditions are successfully met, the charges can be dropped or remain dormant.

- If the agreed conditions are breached, the prosecution can resume, and the individual can be charged.

Outcome 20 – action undertaken by another body or agency

- The case is passed to another body or agency to progress (e.g., mental health service).

- Victim (or person acting on their behalf) is made aware of the process.

- Considered by the police to be no further action.

Outcome 21 – not in the public interest – police decision

- Further investigation to support formal action being taken is not in the public interest.

- Considered by the police to be no further action.

Executive summary (Back to top)

Inspection methodology

The fieldwork for this inspection involved visiting eight youth justice services (YJS) within six police force areas. HM Inspectorate of Probation inspected a total of 98 cases: 88 involving children who had received a youth community resolution or Outcome 22, and 10 involving other types of disposals.

We assessed the quality of decision-making in an additional 66 cases where the children received a youth caution (YC) or a youth conditional caution (YCC). We made some comparisons between the work delivered under Outcome 22 and community resolutions and found the differences to be negligible.

HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services inspected the quality of disposal decisions made by police officers. The police crime outcome types that we focused on were:

- Outcome 8: a community resolution (with or without formal restorative justice) applied in accordance with policing guidance.

- Outcome 20: further action resulting from the crime report is undertaken by another body or agency other than the police, subject to the victim (or person acting on their behalf) being made aware of the action being taken.

- Outcome 21: further investigation resulting from the crime report that could provide evidence sufficient to support formal action being taken against the suspect is not in the public interest – police decision.

- Outcome 22: diversionary, educational or intervention activity, resulting from the crime report, has been undertaken and it is not in the public interest to take any further action.

We held a range of meetings and focus groups with staff delivering OoCDs, their managers, and senior leaders at a national level. We commissioned User Voice to conduct surveys and interviews with 50 children, and inspectors spoke with 31 parents or carers, gathering their perspectives on the services they received. These were not necessarily the children or parents or carers whose cases we inspected. A report from User Voice will be published alongside this report.

More information about our inspection methodology can be found in Annex 2.

Governance and leadership

We found a broad consensus on the importance of avoiding the unnecessary criminalisation of children, with national and local commitments to child-centred justice. The overall approach to OoCDs was, however, fragmented and hindered by inadequate data, oversight, and strategic direction.

Inconsistent police recording of crime outcome types, limited tracking, and the inability to disaggregate data specific to children undermined efforts to monitor trends, assess reoffending, and evaluate the impact and cost effectiveness of interventions. This undermines public confidence and limits the quality and consistency of support available to children.

The YJB first-time entrants (FTE) key performance indicator, a measure of children’s entry to the justice system, no longer reflected the reality of a system where most cases were managed through OoCDs. A more meaningful and comprehensive measure was needed.

Most existing research had focused on the negative impacts of formal youth justice system involvement on children, rather than identifying the key elements of successful diversion.

We found wide variation in the use of tools such as the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) child gravity matrix and disposal options like deferred prosecutions. This had created a ‘postcode lottery’ in decision-making and fostered perceptions of unfairness. We also found some confusion about how different police crime outcome types affected what may be disclosed later, for example to employers – which can have a significant impact on children’s life chances.

At the local level, youth justice partnership boards did not have a clear understanding of the overall volume of OoCDs or the effectiveness of interventions involving the YJS and other partners. Some services faced capacity challenges, and while Turnaround funding was welcomed and generally used effectively, the short-term and uncertain nature of some funding streams made it difficult to develop sustainable, long-term strategies.

Addressing these challenges requires stronger national frameworks, clearer guidance, improved data systems, and more effective multi-agency collaboration to ensure children have access to the right support at the right time.

Policing and decision-making

A significant number of children, including those involved in serious offences, were being dealt with informally, often by police alone and without YJS involvement. We saw cases where children were wrongly told they had to complete interventions or face prosecution, which was both inaccurate and potentially coercive. Where decisions were made in conjunction with the YJS, procedures were not always followed to ensure the most suitable disposal, and decision rationales were often unclear, leading to a lack of transparency.

Police officers did not routinely use the NPCC child gravity matrix and associated guidance, even in cases involving serious offences such as violent or sexual crimes. We found occasional tensions between the police and partner agencies over final disposal decisions, particularly in more serious cases such as those involving knives.

Patterns of repeat offending were not always considered when making police-only and joint decisions about OoCDs involving children. This oversight could result in the same child receiving multiple disposals without appropriate escalation or timely intervention.

In some instances, Outcome 20 and Outcome 21 were used inappropriately for serious offences, which undermined the concerning nature of the crimes and the need for appropriate responses. The widespread and largely unmonitored use of Outcome 20, including in school settings, raised concerns about whether children and communities were kept safe and victims supported. Without clear national data and oversight, the full scale and impact of these practices remained unknown.

Partnerships and services

Although support under OoCDs tended to be shorter than the statutory orders these children might previously have received, the complexity of their needs, circumstances, and, in some cases, the risks they posed to others, remained unchanged. Given the brevity of OoCDs, swift access to services and sustained support was vital.

Access to education and intervention for emotional health and wellbeing were the biggest challenges and often remained unmet at the end of the OoCD. Support frequently arrived too late, ended prematurely, or lacked proper exit and onward planning, leaving many children without the continuity of care and help they needed. Integration with services such as children’s social care was essential. Without coordinated and timely intervention, children on the edge of the justice system remained at significant risk of further escalation.

Victims’ services need to improve to ensure effective engagement processes, uphold the Victims’ Code, and amplify victims’ voices, especially those of child victims, whose age and maturity must be carefully considered.

Interventions were not always jointly planned, delivered, reviewed or sustained. Even when services were available, referrals were not always made or could be declined for unclear reasons, and there was limited analysis of engagement or referral patterns. Addressing these gaps could significantly improve the outcomes for children.

The quality of youth justice casework

YJS staff demonstrated strong skills in engagement, with their support highly valued by children and parents or carers. Many of the children had significant safety and welfare needs, often facing multiple challenges that increased the risk of reoffending if left unaddressed.

In many cases, there needed to be greater emphasis on safety, for both the child and others, in all aspects of practice. Interventions tended to focus narrowly on the offence rather than addressing the underlying risks and safeguarding concerns, which were closely linked to reoffending. A growing number of children displayed escalating, concerning behaviours requiring more intensive, tailored support.

Given this complexity, the system must adapt to provide structured, needs-led interventions that address the root causes of offending and are beneficial for children, including through support delivered outside the justice system where appropriate.

Recommendations (Back to top)

Correction: Recommendation 10 was amended on 05.12.2025 to replace ‘accepted responsibility’ with ‘admitted guilt’.

The Home Office should:

- amend crime outcome types to clearly distinguish between Outcome 22 (no further action), deferred youth cautions, and deferred prosecutions. Also, consider whether deferred youth cautions and deferred prosecutions should be formally recognised as positive police outcomes

- ensure that out-of-court disposals data for children is separated from that for adults.

Ministry of Justice should:

- work with the Home Office and Youth Justice Board to review the relevance, suitability, and effectiveness of the first-time entrants key performance indicators, and implement new reporting processes for all out-of-court disposals. This includes tracking Outcomes 20 and 21

- include all out-of-court disposals where interventions are delivered to children, including community resolutions and Outcome 22, in criminal justice system reoffending statistics.

The Home Office and Ministry of Justice should:

- remove youth cautions from the out-of-court disposal framework, and explore the feasibility of introducing statutory deferred prosecution schemes and statutory provision for community resolutions.

The Home Office, Ministry of Justice, and the Youth Justice Board should:

- evaluate the data on outcomes delivered to children to understand the effectiveness of out-of-court disposals in reducing reoffending.

The National Police Chiefs’ Council should:

- amend the NPCC child gravity matrix guidance so that any divergence of more than one score must be authorised by an officer of at least the rank of police inspector

- amend the NPCC Community Resolutions Guidance to include standardised wording for community resolution forms, to ensure consistency and to prohibit the use of coercive wording.

- work with the Youth Justice Board and Home Office to develop guidance in relation to the use of Outcome 20 and 21. This should include referral to youth justice services when appropriate (in accordance with the NPCC child gravity matrix guidance).

The National Police Chiefs’ Council, College of Policing, and Youth Justice Board should:

- amend the NPCC Community Resolutions Guidance, the College of Policing Authorised Professional Practice for prosecution and case management, and the YJB case management guidance to reflect that community resolutions are issued only when the child has admitted guilt or where there is evidence that would provide a realistic prospect of conviction.

Chief constables should:

- improve how out-of-court disposals are managed by:

- working with YJSs to establish formal data-sharing arrangements to ensure timely and consistent access to information on all types of out-of-court disposal

- ensuring decisions about the use of crime Outcomes 20 and 21 are consistent and appropriate and reflect revised NPCC guidance

- ensuring that police always use the NPCC child gravity matrix guidance when making decisions relating to outcomes for children and that the rationales for those decisions are always recorded.

- ensuring that joint decisions with the youth justice service about out-of-court disposals are made at the appropriate level of seniority.

- ensuring that children’s legal rights are met before issuing a community resolution; this includes the need to caution and make sure that an appropriate adult is present

- ensuring that safeguarding referrals are made when appropriate.

The Youth Justice Board should:

- ensure that current data collection mechanisms support future evaluation of the effectiveness of out-of-court disposals in outcomes for children, reoffending rates, potential net-widening, and their cost-effectiveness

- work proactively with youth justice partnership boards to help them build a clear understanding of all out-of-court disposals used locally, evaluate their impact, and ensure their effectiveness

- work together with partners to establish an evidence base about which interventions and disposals are most effective in reducing reoffending and delivering positive outcomes for children.

Youth justice partnership boards should:

- In line with the case management guidance:

- collate data on all out-of-court disposals, including from partner agencies, to analyse and monitor use, to ensure appropriate application, identify trends, and assess for net-widening

- ensure all partners take a collaborative approach to out-of-court disposal decision-making and intervention delivery, supporting joint work and effective exit planning.

Youth justice service managers should:

- consider the complexity and nature of the risk and safety concerns for each child, and match these with the skillset and experience of staff when allocating work

- improve the quality of assessment, planning, and service delivery so that they focus equally on supporting the child and keeping them and other people safe

- ensure that children and their parents or carers understand the requirements of the out-of-court disposal and the aims of their intervention plan.

1. Introduction (Back to top)

1.1. Why this thematic (Back to top)

In 2018, HM Inspectorate of Probation, with HM Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS), conducted an inspection into the delivery of OoCDs (HM Inspectorate of Probation, 2018). The resulting report made 11 recommendations, emphasising the need for greater focus on victims and a comprehensive evaluation of the use and effectiveness of OoCDs.

Since then, the use of OoCDs has increased significantly and now accounts for most casework in many youth justice services (YJS). Aggregated data from core youth inspections conducted by HM Inspectorate of Probation between 2021 and 2024 indicated that most aspects of OoCD practice were rated as ‘Good’, with efforts to promote desistance identified as a particular strength. However, the findings also highlighted significant differences in how OoCDs were handled across areas, raising concerns about whether children were receiving fair and equal outcomes.

This thematic inspection provides an evaluation of the evolving use of OoCDs, alongside the implementation of new guidance, including the updated Youth Justice Board case management guidance for England and Wales (YJB, 2024), and the National Police Chiefs’ Council child gravity matrix (NPCC, 2025).

The overarching aim has been to promote a better understanding of OoCDs across England and Wales, and clarity and consistency in processes and practices.

1.2. Background (Back to top)

Legislation

The Crime and Disorder Act 1998 placed an emphasis on preventing offending, particularly among children. It introduced a legal duty for local authorities, police, health services, and other public bodies to make crime prevention a shared responsibility across services. One of its key measures was the creation of youth offending teams (YOTs), which brought together professionals from different sectors to work collaboratively in tackling youth crime and preventing reoffending.

The act marked a significant shift toward a multi-agency, preventative approach to crime, embedding responsibility for crime reduction into the everyday work of public services and encouraging early, community-based responses rather than relying solely on punishment.

Youth Justice Blueprint for Wales

The Youth Justice Blueprint for Wales was established in 2018–19 by the Welsh Government, HM Prison and Probation Service, and Youth Justice Board Cymru. It places a strong emphasis on out-of-court disposals and diversion to prevent the criminalisation of children. It promotes early intervention and targeted prevention by addressing underlying factors such as trauma, adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), and unmet welfare needs. The approach prioritises keeping children out of the formal justice system wherever possible, using restorative, trauma-informed, and multi-agency methods to resolve issues without prosecution. By strengthening the use of pre-court interventions and ensuring consistency across Wales, the Blueprint aims to support better outcomes for children.

Bureau (youth diversion panel)

Bureau is a Welsh scheme for children who admit low-level offences. First developed in Swansea, in conjunction with South Wales police, it is rooted in a ‘Child First’ ethos, now used across Wales and parts of England.

Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012

The Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012 (LASPO) significantly changed the framework for OoCDs for children in England and Wales. It replaced the previous system of police reprimands and final warnings with youth cautions (YCs) and youth conditional cautions (YCCs).

The changes introduced by LASPO aimed to simplify and standardise how minor offences committed by children were handled, focusing more on rehabilitation and restorative justice. The goal was to reduce the unnecessary criminalisation of children, decrease reliance on courts for low-level offences, and give police and YJS more flexible tools for early intervention.

Community resolutions – informal, non-statutory police measures which were initially used for low-level, first-time offences – were not part of LASPO; they are guided by police discretion rather than legal requirements.

The code of practice for victims of crime in England and Wales

The ‘Victims’ Code’ outlines the rights and support available to victims of crime, ensuring they are treated with dignity and respect in the criminal justice process.

Under the code of practice, victims have the right to clear communication, proper recording of their crime report, and updates on investigations. Victims have the right be asked for their views and for these to be considered when a disposal decision is made. Where this is not possible, the reasoning must be explained to victims. They can access support services and make a victim personal statement about the crime’s impact.

Victims should be kept informed about the trial, outcomes, and custody release decisions. Special measures can be provided for vulnerable victims during court proceedings, and victims should be informed about restorative justice options. If their rights are not met, they can make a complaint.

The NPCC child gravity matrix

In 2023, the National Police Chiefs’ Council (NPCC) published the child gravity matrix (CGM). This replaced the 2013 ACPO youth offender case disposal gravity factor matrix.

The revised matrix expanded gravity scores from a 1–4 range to 1–5. A score of 1 applies to cases suitable for no further action, while a score of 5 typically leads to a charge. Scores 2, 3, and 4 correspond to informal out-of-court disposals, YCs, and YCCs respectively. Outcome 22 should be used for offences that are gravity 2-4. The revised matrix also allowed for more discretion in the final disposal decision.

The child gravity matrix was updated with the most recent version in 2025. These revisions included:

- a revised scoring system to assess aggravating and mitigating factors

- updating the guidance to include all OoCDs

- updated offence categories to reflect current crime trends and legislative changes

- improved guidance aimed at promoting fairness and consistency in decision-making.

The matrix aims to provide consistency in the use of OoCDs across police force areas. It helps officers determine the most appropriate outcomes or disposals for children who commit offences.

National standards for children in the youth justice system (YJB, 2019)

The YJB national standards, last updated in 2019, emphasise a child-centred, early intervention approach to out-of-court disposals, aiming to prevent the unnecessary involvement of children in the criminal justice system: ‘All action should be taken to promote diversion into more suitable child-focused systems, and the promotion of positive constructive behaviour.’(National Standards, 2019)

Standard 1, out-of-court disposals, emphasises early diversion from crime through multi-agency collaboration, clear separation between diversion and formal disposals, and child-focused, proportionate responses. A joint police-YJS protocol must guide decision-making, with quality assurance in place and a focus on reducing disproportionality. YJSs must carry out thorough, timely assessments to inform intervention plans that support pro-social behaviour. Children and their families should be involved in all stages.

The standards promote a ‘Child First’ approach, focusing on the child’s wellbeing and development, with an emphasis on positive behavioural change.

YJB case management guidance and assessment tool

The YJB’s case management guidance on OoCDs was first published in 2019 with an update in 2022. The guidance covers key areas such as decision-making, collaboration between the police and YJS, victim involvement, and procedures for reviewing decisions. A further update in January 2024 placed greater emphasis on promoting consistency in OoCD delivery and ensuring that approaches are fair and tailored to the individual needs of children. It sets out clear, standardised decision-making processes that take each child’s circumstances into account. The guidance also encourages the use of diversionary measures as alternatives to formal court proceedings, with the aim of reducing reoffending and supporting children’s rehabilitation.

In April 2024, the YJB released the national prevention and diversion assessment tool (PDAT), accompanied by guidance and quality assurance documents. National training was delivered to support its implementation, and the tool was deployed across all YJSs in England and Wales.

Relevant issues

Racial disproportionality

Over the past decade, the number of children in the formal youth justice system fell by 67 per cent, yet the proportion of Black children rose. By 2024, they made up 11 per cent of those cautioned or sentenced, up from 9 per cent in 2014. The Lammy Review into treatment of, and outcomes for Black, Asian, and minority ethnic individuals in the criminal justice system (2017) cited mistrust of police among Black and minority ethnic youth, making them less likely to admit guilt – required for most OoCDs. Outcome 22 was introduced to bypass this barrier, allowing intervention without admission of guilt. There has been no national evaluation to assess if Black and minority ethnic children have benefited from the use of Outcome 22.

Concerns about potential net widening

Longstanding concerns have been raised that the use of OoCDs might lead to ‘net widening’, potentially drawing into the criminal justice system more children who would not have been considered serious enough for formal processing, thereby increasing the risk of stigmatisation (Centre for Justice Innovation, 2024).

Research and findings[2]

There was limited up-to-date research on the effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of the differing types of OoCD, including which types might work best with which children, taking into account children’s differing histories and circumstances. However, the available evidence broadly indicated that diverting children from the formal youth justice system for low-level offences was effective in reducing reoffending. Although the precise mechanisms were not fully understood, evidence pointed to a labelling effect, where involvement with the justice system increased surveillance and reinforced antisocial identities and behaviours. For instance, the Edinburgh Study of Youth Transitions (McAra and McVie, 2007) found that children known to the justice system were slower to desist from offending than those who were not.

Other evidence showed that diversion programmes – especially voluntary ones like community resolutions – worked best when children were sufficiently engaged and motivated to take part. Marshall (HM Inspectorate of Probation, 2023a) stressed that a young person’s willingness to get involved was key to making these approaches successful. However, the report also raised concerns about those who received several community resolutions without any positive changes in behaviour, showing that these measures may not work well if the young person is not truly motivated and engaged.

National key performance indicators

The national first-time entrants (FTE) key performance indicator (KPI) in the youth justice system measures the number of children who receive their first formal criminal justice outcome. This outcome can be a caution, a conditional caution, or a court sentence. The KPI helps track the number of children entering the youth justice system for the first time.

Although the YJB collected OoCD data from YJSs, its completeness and reliability remained unclear, preventing publication to date. As a result, little was known nationally about who received OoCDs, their impact on reoffending, or any disproportionality across different groups or local areas.

This inspection sought to answer the following questions:

1. Do governance and leadership arrangements drive high-quality services that achieve positive outcomes for children receiving OoCDs, while promoting their safety and the safety of others?

2. Do well-defined policies, processes, and effective multi-agency partnerships support timely and appropriate diversion of children from the formal justice system, with actions to achieve positive change and keep children and the community safe?

3. Do policies, processes, and practice consistently consider national guidance such as the NPCC child gravity matrix, YJB case management guidance, Outcome 22, and community resolution guidance?

4. Are staff empowered to deliver high-quality, personalised, and responsive services to achieve positive change and keep children and the community safe?

5. Do effective relationships and arrangements with partner agencies ensure access to responsive services and interventions that drive positive change and keep children and communities safe in the delivery of out-of-court disposals?

6. Do partnership arrangements promote and facilitate effective service delivery for all children diverted from the criminal justice system?

7. Is timely and relevant information available and shared effectively to support a high-quality, personalised, and responsive approach for children receiving an OoCD, including support for their safeguarding and wellbeing, and the safeguarding of others?

8. Is service delivery well-informed and personalised, and effective in analysing how to achieve positive change and keep children and other people safe?

Scope of the inspection

The inspection covered the work of the police in their direct delivery of OoCDs to children, police safeguarding practices, information sharing with YJSs, and the police contribution to decision-making in cases referred to the YJS for consultation and input. It also examined the effectiveness of information sharing with the YJS to inform assessments and ongoing work.

We considered how the police, YJS, and other partners worked together to understand the circumstances of the children, the context of their offending, their personal histories, their vulnerabilities, and any risk their behaviours posed to other people, including those who had been direct victims of their offending.

We assessed the effectiveness of how partners worked together to understand and meet the needs of children, as well as how the work of their individual agencies contributed to supporting the diversion of children from the formal youth justice system. Additionally, we examined how well ongoing support, where it was needed, was coordinated between services to sustain efforts aimed at reducing the risk of reoffending.

We inspected the assessing, planning, and delivery of interventions, and the outcomes achieved. We also separately considered cases where the decision was made to impose a YC or YCC, although we did not inspect the quality of casework in these cases, as the delivery of these interventions was governed by a statutory framework.

Our inspection samples were limited to OoCDs, so we were unable to compare them with court disposals to assess any disparities in outcomes for similar offences.

The methodology for this inspection differed from that used in the inspection of out-of-court disposal cases in our Youth Core Inspection Programme (2018-2024). For this inspection, we had prior knowledge of children’s history of contact with the police and accessed social care records. We assessed outcomes for the children and the progress they had made during and after the intervention period.

Report outline

| Chapter | Content |

| 2. Governance and leadership | This chapter examines how national and local strategic leadership, along with empowered staff and managers, contribute to delivering high-quality services for children receiving OoCDs. It also explores how data is used to evaluate service effectiveness and the overall diversion approach. |

| 3. Policing and decision-making | This chapter examines key considerations in the recording and resolution of crime by the police. It examines how crimes are recorded and the range of crime outcome types used. Incidents in schools, victim engagement, and safeguarding notifications are also addressed. |

| 4. Joint decision-making | This chapter examines joint decision-making processes, how the YJS informs those decisions, and their effectiveness in reaching the right disposal outcome. |

| 5. Partnerships and services | This chapter examines the effectiveness of partnership working, including access to both specialist and mainstream services, as well as the availability of support for exit planning and ongoing help for children. |

| 6. The quality of youth justice casework | This chapter explores how youth justice practice supports desistance, promotes children’s safety and wellbeing, addresses risk management, and considers the needs of victims. |

2. Governance and leadership (Back to top)

2.1 National leadership and policy context (Back to top)

The increasing use of OoCDs reflected a broader shift toward a more child-centred, welfare-oriented approach to justice. Since the previous joint inspection in 2018, OoCDs have been applied across a wider range of offences and disposal types. This largely organic growth had been driven by a strong national commitment to divert children from formal criminal proceedings where appropriate – a position unanimously supported by the national leaders consulted during this inspection.

Although policies and guidance had increasingly supported diversion, including for more serious offences, this shift had occurred without a comprehensive national framework. National leads raised concerns about the lack of clear structure guiding the development and use of OoCDs. As one participant noted:

“There is no obvious national policy driving the use of OoCDs. It’s more of a grassroots approach in policing, particularly in the use of Outcome 22. There’s no national framework, no structure. There is no accountability, no monitoring, and very little data to support it.”

In the absence of a statutory framework, concerns had grown among some that OoCDs risked becoming a ‘quasi-judicial process’ lacking transparency and accountability.

The Home Office and Ministry of Justice had allowed local police forces flexibility within national OoCD guidance to tailor responses to local community needs. While this approach was intended to enhance efficiency and effectiveness, it had led to significant variation and limited standardisation across regions. The resulting lack of a ‘level playing field’ had raised concerns about fairness, accountability, and public confidence.

We found widespread agreement among government departments and stakeholders on the need for clearer national direction, structured oversight, and consistent data collection to ensure OoCDs were applied fairly and effectively.

Data challenges and limitations in national oversight

Unlike statutory interventions, monitored by the YJB, there was no clear picture of the outcomes for children receiving other types of OoCDs, despite these children now comprising the majority of youth justice work in many areas.

At the time of our inspection, Home Office recording of OoCDs did not differentiate between children and adults, other than for YCs and YCCs. As a result, there was no effective way to examine or track the specific use of OoCDs for children at a national level. The increasing use of various crime outcome types (see Chapter 3) added complexity, as they were used differently and to varying degrees across the country, depending on local decisions about which outcome types to apply and how.

The absence of robust data undermines trust in the system and limits the ability to evaluate its true impact. It raised concerns about potential under-reporting and misrepresentation of youth offending. Since these cases are processed outside the formal justice system, they risked becoming statistically invisible.

Magistrates raised concerns about inconsistent use of OoCDs across and within police areas, finding the range of options complex. Some advocated for earlier court involvement in certain cases given the short duration and voluntary nature of OoCDs. There was also a call for greater trust in youth court sentencers to adopt a child-centred approach to sentencing.

A Magistrates’ Association representative recalled a recent case and told us:

“There is a loss of confidence when a child ends up in court for a knife offence and then you find out they have had 22 previous OoCDs and then they go to custody.”

In 2023, the Ministry of Justice introduced new key performance indicators and reporting requirements for YJS, partly to strengthen national oversight of OoCD use. These were operationalised by the YJB. KPI 6, on out-of-court resolutions, measures the proportion of children receiving out-of-court disposals and their completion rates. Those managed solely by the police are not counted.

The first dataset was published in June 2025, after fieldwork on this inspection had concluded. Although the data is not yet suitable for analysis or decision-making, this represents a step forward in capturing data for children managed by the YJS.

Reports were expected to be available for analysis in 2026/27, but it remained unclear whether they would include details such as the number of OoCDs received by individual children.

A long-standing joint inspectorate recommendation to include community resolutions in criminal justice system reoffending statistics (HM Inspectorate of Probation, 2018) had not been enacted. Since then, this had become increasingly significant, as the use of community resolutions and other out-of-court disposals had grown and now represented the majority of YJS casework in many areas.

Limited data on OoCDs made it difficult for some stakeholders to fully support the approach, raising concerns about whether the focus remained on children’s best interests or had shifted, towards easing system pressures.

Most research tended to highlight the harms of criminal justice involvement rather than identify effective diversionary practice in England and Wales. The Home Office, in partnership with the Youth Endowment Fund (YEF) and the NPCC, was undertaking a large-scale research project to improve the national understanding of how OoCDs were used for children and to enhance the quality of related data, including the use of crime outcome types.

Youth cautions

We found some inspected YJSs did not use YCs as a disposal option because no interventions can be given with this disposal. In those areas, Outcome 22 NFA was usually used instead. We also found that in some areas, YCs had been given by the police without referring the case to the YJS for an assessment and joint decision about the most appropriate disposal.

It is generally believed to be better to provide interventions alongside OoCDs as this is considered more likely to address the reasons for the offending and reduce the chance of reoffending. While this principle underpins the adult two-tier caution framework introduced by the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Act 2022, it had not been applied to children.

We believe that a new statutory framework is needed for OoCDs for children. This framework should include provisions to make sure that interventions are part of OoCDs where appropriate, so that decisions about disposals can be deferred until interventions have been delivered and successfully completed.

Given the inconsistency and practices surrounding the delivery of community resolutions (as detailed further in the report), we believe consideration should also be given to including them within a revised statutory framework.

Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) checks

The desire to avoid children receiving criminal records emerged as a key theme and was a major factor behind the growing use of OoCDs, even for more serious offences, diverting children from the formal justice system to prevent court appearances and criminal records, which could significantly impact their future. There was some confusion about the significance of the various police crime outcome types used to close crimes and a perception that some were more likely to lead to future disclosure than others in terms of future disclosure. However, according to the Youth Justice Legal Centre guide published in June 2025 this is not the case. The guide states that:

‘No informal OOCDs, such as community resolutions and Outcomes 20, 21 and 22, come under the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974, so they are never considered “spent” or “unspent”. Informal OOCDs will never be automatically disclosed in DBS checks.

Youth cautions will not be automatically disclosed in DBS checks (basic, standard or enhanced). They are immediately filtered from DBS checks when they are administered. They also become immediately “spent” once they are administered. The recipient would never have to declare them to an employer as part of their application, unless they are applying for an occupation that is an exception under the Rehabilitation of Offenders Act 1974 (Exceptions) Order 1975. YCCs become spent and filtered after 3 months from the date they are administered, or when the conditions of the caution are met. After this, they will not be automatically disclosed.’

Although not automatically disclosed, the police have the discretion to include non-conviction information, such as formal and informal OoCDs, on enhanced DBS checks. In all cases, disclosure is permitted only if the information is relevant, necessary to disclose, and proportionate, considering both the protection of the public and the rights of the individual.

We consulted directly with the DBS to understand the rate of disclosure. Data on applications was not broken down by age, so it was not possible to identify the exact number of cases involving children. However, we were told that over a period of 12 months, 4.2 million requests for enhanced DBS checks were made, of which three million were referred to police forces for consideration, and 4,500 actual disclosures made. This equated to approximately 0.1 per cent for both children and adults.

National policing strategy

The NPCC has a national strategy for OoCDs aiming to standardise and enhance their use across England and Wales. However, since the strategy is guidance-based rather than mandatory, its implementation is left to individual police forces. This had led to inconsistent OoCD practices nationwide, making it challenging to maintain uniform standards or gain a comprehensive understanding of their national use.

The NPCC views the use of Outcome 22 as aligning with Child First principles, which emphasise informal intervention over criminalisation. But the inconsistent introduction of Outcome 22 has resulted in uneven outcomes for children.

Our inspection found no evidence of an effective deferred prosecution scheme. There needs to be a greater understanding of the implications of wider use of deferred prosecution schemes and how they fit into the OoCD framework. We discuss this further in this report.

Safeguarding children who come to police attention is paramount to the NPCC. The expectation is that this is done through referrals, when appropriate, to children’s social care. However, we found that this did not happen consistently in practice, both for children who had offended and their often-vulnerable victims. In our sample, 42 per cent of victims were children, yet safeguarding referrals were not routinely made for either victims or children suspected of committing an offence.

The NPCC, agreed that although diversion was often the preferred approach, charging a child was sometimes necessary.

Responsibility for OoCD decisions ultimately rests with the police. The YJS is responsible for providing expert advice on the child’s background and circumstances to help ensure the disposal was suitable. In some cases, the CPS might also be involved to offer guidance or approve specific disposals. Despite decision-making responsibility lying with the police, the NPCC was frequently approached by forces seeking clarification on decision-making responsibilities. This raised concerns about how well the national guidance was understood and whether references to ‘joint decision-making’ could be causing local confusion and tensions (see Chapter 4).

The NPCC was focused on achieving the right outcomes for the child. The NPCC emphasised that the quality, structure, and impact of the interventions for children must be considered. The nature of the offence alone should not determine whether an OoCD was the most appropriate response.

The NPCC and the YJB reported a positive working relationship. However, the departure of an embedded police superintendent from the YJB a few years ago created a gap. Although the NPCC continued to engage with the YJB, this level of involvement did not provide the same benefits as having an embedded presence.

National oversight and governance of youth justice service delivery

The YJB is responsible for overseeing the youth justice system in England and Wales. It advises the secretary of state for justice, monitors the performance of the system, promotes best practices, and advocates for children. The YJB promotes a ‘Child First’ approach, which prioritises the welfare and development of children in understanding and addressing their offending behaviour.

The YJB had a detailed understanding of statutory youth justice delivery, informed by data submitted by the YJS and the Police National Computer. Data collected under KPI 6 on out-of-court resolutions should help to broaden this understanding.

Inconsistencies in approaches to OoCDs had been a concern for some time, with YJSs using different assessment tools. To address this and enhance data collection, the YJB introduced the prevention, diversion, and assessment tool (PDAT) in 2024, accompanied by national guidance and training to support its implementation.

The YJB had introduced a new oversight model that categorised YJSs into performance-based quadrants, with YJB representatives attending quarterly youth justice partnership board meetings to provide support and monitor local service performance.

The YJB case management guidance advises that case closure and exit planning should ensure children do not remain open to services unnecessarily, and that where needs remain, appropriate support, whether within or beyond the YJS, continues to be provided. In practice, interventions were typically limited to 12 weeks, and often less. The shorter timeframe for OoCDs might reflect a broader emphasis on minimising contact with the youth justice system wherever possible, in line with the ‘Child First’ approach. This risked shifting the focus from what a child’s case required to what could be achieved within that limit.

The first-time entrant indicator had helped encourage diversion away from the criminal justice system, reducing ‘net widening’ – the unnecessary criminalisation of those involved in low-level offences where statutory interventions add limited value. However, our inspection raised concerns that net widening may still be occurring, but with children being dealt with in different ways. The understanding of this is limited by incomplete data on the use of some OoCDs.

Local partnership boards should oversee all OoCD use, including those issued solely by police. However, YJSs were not always informed of all OoCDs issued, especially those closed with police Outcome types 20 and 21. While collaboration and data sharing between YJSs and police were developing, further progress was needed to ensure consistently effective oversight.

2.2. Local youth justice governance, leadership, and staffing (Back to top)

Governance and strategic direction of youth justice services

The youth justice partnership board was responsible for setting the strategic direction for the delivery of youth justice services, including OoCDs:

‘Youth justice management boards and partnerships have an important role in ensuring that Child First, trauma-informed principles and other child-focused approaches are embedded strategically and operationally.’ YJB, Governance and Leadership Guidance (YJB, 2021)

Every board had a clear vision for children based on ‘Child First’ principles, with a strong focus on diversion and early intervention to address offending behaviour and prevent entry into the formal justice system. This commitment was reflected in youth justice plans, which were developed with input from strategic partners and aligned with local priorities.

Some boards were well established and cohesive, while others were in the early stages of development. In one area, nearly all board members had attended only two meetings. In some areas, challenges related to staffing and resourcing had hindered the development of high-functioning boards, limiting their ability to provide effective oversight.

In the best examples, partners worked together to identify gaps in understanding the profile of children receiving OoCDs and the barriers to their effective use. In Dorset, challenges in tracking reoffending after children turned 18 were raised with the board. The police were tasked with retrieving this data and provided it, enabling the partnership to better assess the effectiveness of its approach to reducing reoffending.

Funding and resourcing arrangements

Funding arrangements varied significantly across the services inspected. All reported that short-term and late-allocated funding posed significant barriers to long-term planning.

The Turnaround Programme, led by the Ministry of Justice, provided time-limited funding to most local authorities for early intervention services aimed at children at risk of offending and entering the formal justice system. All inspected areas received Turnaround funding, which was used effectively to enhance services such as mentoring, education support, and positive activities; its one-year extension was welcomed.

Most inspected areas received funding from their Police and Crime Commissioners, boosting YJS budgets and resources, though support varied by region based on priorities, budgets, and local youth justice strategies.

Some services struggled to meet rising demand, particularly as OoCD use grew and children required more intensive support. In one area, high caseloads made it difficult to take on new cases without closing existing ones.

One leader acknowledged the challenges of delivering effective OoCD work within existing resources:

“There has been no change in YJS resourcing or funding in the past 10 years. This raises the potential for a disconnect between national expectations of service delivery and what is realistically achievable.”

The use of data and information to analyse effectiveness

While boards recognised key issues affecting children, such as gaps in education and emotional wellbeing, they often lacked a full understanding of their backgrounds and offending histories.

Reoffending data was sometimes analysed but often unreliable or lacking detail. There was little evidence of data collection on police-issued disposals like community resolutions and Outcomes 20 and 21, hindering evaluation of their use and effectiveness.

Many areas relied on the FTE rate to judge the success of youth diversion efforts. But this measure was not a reliable indicator of reduced reoffending or improved outcomes for children.

To understand whether these children were benefiting equitably from diversion, greater scrutiny was needed of those who were charged, including whether they had been appropriately considered for OoCDs and, if not, why.

There was limited analysis of specific cohorts, such as children from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds. The underrepresentation of this group of children in the OoCD cohort could be either positive or negative; context is crucial, and we found it to be lacking.

The rising number of girls accessing services was recognised, and several areas had developed tailored support to meet their needs. While there was growing awareness, further focus on the social and community factors driving their involvement, particularly in violent behaviour, would enhance the ability of services to respond more effectively.

YJS leadership and management

Youth justice managers showed a strong understanding of children’s needs and the changing nature of the youth justice caseload. They built effective local partnerships and actively advocated for children, with several excellent examples noted of securing access to services such as educational support and speech and language provision.

Clear, well-functioning pathways into both mainstream and specialist services are vital for effective diversion and should be regularly reviewed, with issues escalated to the board when necessary. We saw limited evidence of this happening, partly because the issues were not widely understood. Better evaluation of referral rates, service uptake, and delivery was needed to inform improvements.

Youth justice staff working with children receiving OoCDs consistently demonstrated compassion and strong engagement skills, particularly with children often seen as ‘challenging’. Most staff reported receiving appropriate training and spoke positively about their managers.

However, not all staff fully understood the complexity of their roles, particularly around keeping children and the community safe, and these gaps were not always identified through staff supervision. As a result, training was not consistently embedded into practice, highlighting the need for more targeted support and oversight.

Quality assurance processes did not consistently influence practice. Overall, we found that management oversight was effective in only a third of the inspected cases (ranging between services from 14 per cent to 67 per cent).

This point was highlighted by an inspector:

”Management oversight does not provide sufficient guidance to the practitioner regarding the child’s safety and wellbeing, or in understanding the risks the child may pose to others. This is particularly concerning given the frequency and volume of police information received linking the child to behaviours involving weapon carrying and antisocial behaviour in the community.”

Many practitioners needed clearer support, particularly around assessing risk, safety, and wellbeing, but were sometimes advised to focus primarily on the offence, missing other important factors.

Allocation of work and caseloads

In some services, cases were divided between teams – one focused on early help and diversion, and another on statutory work. These teams often operated under different pay structures and qualification requirements, with statutory teams typically assigned more formal cases. This division could create a perception that statutory cases were inherently more complex or high risk. However, this was increasingly not the case and should not be assumed.

Staff caseloads varied significantly. Some reported very low caseloads, while others ranged between 18 and 20 cases. While staff generally did not report feeling overwhelmed, we observed that many children were seen less frequently than their assessed level of concern warranted.

2.3. Conclusions and implications (Back to top)

There was national and local commitment to avoiding the unnecessary criminalisation of children, with a clear focus on child-centred justice. However, the use of OoCDs was fragmented and inconsistent. Inconsistent crime outcome type recording, limited tracking, and the lack of disaggregated data for children hindered efforts to monitor trends, assess reoffending, and evaluate effectiveness. The first-time entrants key performance indicator, while historically useful, no longer reflected the reality of a system where most cases were managed through a wider range of OoCDs, highlighting the need for a more meaningful and comprehensive measure.

Without a clear national framework, varied local approaches to diversion raised concerns about fairness and public confidence. Meanwhile, an increasing number of children, including those involved in serious offences, were being dealt with informally, often by police alone and without YJS involvement. Despite longstanding recommendations, key data such as on community resolutions remained unpublished, and there was limited evidence on what makes diversion effective.

At the local level, youth justice partnership boards were responsible for overseeing OoCDs, but did not always have sufficient capacity to do so effectively. While Turnaround funding was welcomed and used well, some areas continued to face challenges in managing growing demand and developing sustainable long-term plans.

Unless OoCDs are effective and targeted they can represent a missed opportunity to prevent escalation into the criminal justice system either as a child or an adult. Tackling this requires stronger national frameworks, clearer guidance, better data systems, and more effective multi-agency collaboration to ensure children receive the right support at the right time.

3. Policing and decision-making (Back to top)

3.1. How the police record crime (Back to top)

The public report incidents to the police, who assess whether a crime has been committed. If so, the crime must be recorded. Following the recording of a crime, the police investigate and finalise it with a specific crime outcome type. This is done in accordance with the Home Office Counting Rules for Recorded Crime in England and Wales and a shortened version of the rules called the ‘Home Office Crime Recording Rules for frontline officers and staff’. These two sets of rules tell police forces how they should record crime. In this report, we refer to these sets of rules collectively as the Home Office crime-recording rules (HOCRR).

When deciding the most appropriate disposal for children who have committed an offence, the National Police Chiefs’ Council child gravity matrix (NPCC CGM) should be used. This is described as: ‘a triage tool to support decision-making for officers, to assist in deciding the most appropriate outcome or disposal for those children and young people under the age of 18 years who offend.’

In the 179 police-only decision cases we looked at as part of our inspection, there was evidence that the NPCC CGM had only been used in 35 cases.

Crime outcome types

HMICFRS inspectors examined four crime outcome types, which we describe later in this chapter. They were:

- Outcome 8

- Outcome 20

- Outcome 21

- Outcome 22.

The joint inspection team visited eight local YJSs operating within six police forces. For the eight local YJS areas, we asked each of the six forces to provide data on the number of recorded crimes, over the previous three financial years, where a child was considered a suspect.* These are shown below:

| Outcome | 2021/22 | 2022/23 | 2023/24 |

| 8 | 2418 | 2950 | 3547 |

| 20 | 1391 | 1263 | 1213 |

| 21 | 1396 | 1417 | 1040 |

| 22 | 783 | 1023 | 965 |

| Total | 5988 | 6653 | 6765 |

*Not all forces we inspected were able to break down data to local youth justice services for the three-year period so force data has been included where relevant.

Figure P1

The table shows that between 2021 and 2024, the total number of crimes that the six forces had closed with these crime outcome types had risen from 5,988 to 6,765. As previously highlighted, the Home Office and Ministry of Justice were unable to provide specific data on these crime outcome types as the data collection (other than youth cautions) does not differentiate between adults and children. None of the forces we inspected routinely gathered or shared information on OoCDs with the local YJS. This meant that the lack of disaggregated data prevented any meaningful analysis of the national or local picture.

During our inspection, we found the forces had different systems and processes to make sure that crime outcome types had been correctly applied. This meant we could not be sure that the crime outcome types applied were always accurate and consistent between forces.

Outcome 8 – community resolutions (CRs)

The HOCRR defines Outcome 8 as: ‘Community Resolution: A Community Resolution (with or without formal Restorative Justice) has been applied in accordance with College of Policing guidance.’

In 2022, the NPCC guidance on the use of CRs was updated within the Community Resolution document (NPCC CR). This is non-statutory guidance. This guidance helps the police to make decisions about how to deal proportionately with lower-level crime. It is aimed at children and adults who have committed a crime for the first time, although forces do have discretion where there is a history of previous offending.

CRs can be an ‘informal agreement’ between the parties involved: ‘They aim to reduce the likelihood of reoffending by encouraging the child to face up to the impact of their behaviour and to take responsibility for making good any harm caused.’

Types of low-level offending are included within the guidance. In the NPCC CGM there are five levels of escalation, and the guidance states that crimes scoring level 2 or 3 are most suitable to be dealt with through CR. The NPCC CR guidance states that CRs can only be given when a person has either admitted their guilt or accepted responsibility for an offence.

The College of Policing’s Authorised Professional Practice (APP) for prosecution and case management also states that: ‘The most appropriate offences to warrant a community resolution are likely to be low-level criminal damage, low-value theft, minor assaults (without injury) and anti-social behaviour.’

We asked the inspected forces to provide us with the numbers of CRs given to children in the three calendar years up to 31 October 2024. The table above (Figure P1) shows that, although there were variations between forces, the overall numbers of CRs given to children had increased significantly over the period 2021/2022 to 2023/2024.

Under the NPCC CR guidance, the police are required to inform the YJS when a CR is issued to a child within 24 hours, using a system commonly called PENY (police electronic notification to YJS). We found the police did not always do this. We asked inspected forces to identify which of the CRs had been dealt with solely by the police, and which had involved the YJS. We were concerned that only one of the forces was able to give us this information.

We also found that unless the child was open to the YJS, little if any action was taken by them when notified of the CR. This meant that the local partnership was often unaware of the number of CRs given to children and the effectiveness of them in reducing reoffending.

During our case file reviews, we found that some CRs were dealt with solely by the police. Other cases were referred to the YJS and joint decisions made by partners. If the police close a crime after a CR has been given it should be finalised as Outcome 8. The Home Office and the police view CRs as a positive outcome, in the same way as a youth caution or conditional caution. All other OoCDs are not viewed as positive outcomes.

During our inspection, we found that in one force, police were encouraged to use CRs as much as possible and actively discouraged from using Outcome 22. We were told by the YJS in this area, that this created tensions between the force and partners.

We were told by a police lead that, despite providing CR training to their officers and raising awareness, guidance was often not followed.

In five of the six forces we inspected, the responsibility for deciding whether a CR was appropriate to be given to a child was left to individual officers and their supervisors. However, in one force (Dorset) we saw a central decision-making team for these types of cases. This provided a more consistent, fair, and effective approach to decision-making. It also considered the interests of the child because the person making the decision was better trained and more aware of the other background factors.

Most forces that we inspected had systems to check that crime outcome types had been correctly allocated to crimes. However, this was often after the case had been concluded, which meant that it could not always be changed if incorrect. One force had reviewed their own CRs: 5,057 CRs had been issued to adults and children over a six-month period; the force had identified that 2,761 had not been completed or recorded correctly. This meant that the local picture may have been inaccurate.

In another force, we were told that the team responsible for making sure that crimes had been finalised correctly had found errors. Despite this, they failed to keep proper records of any amendments made or how many times this had happened or why, so the force could not learn from its mistakes.

We also found that the police did not routinely inform the YJS when they issued CRs to children. The YJB case management guidance says: ‘Police should notify the YJS of all Community Resolutions issued to a child within 24 hours. Depending on local arrangements, where the YJS has not been involved in the decision making, it is best practice for the YJSs to screen the children involved and offer voluntary support where appropriate.’

The forces we inspected provided the total number of crimes for which children had received a CR in the year ending 31 October 2024.* These are shown below:

| Crime category | Number | % |

| Violence | 1282 | 41 |

| Theft | 774 | 25 |

| Drugs | 367 | 12 |

| Other (incl. sexual and firearms) | 672 | 22 |

*Individual cases provided for each youth justice service.

Case audit analysis

We reviewed 87 CR cases. We found that 41 of the children had previously offended. Of these 41 children, 27 had three or more crimes attributed to them. We were concerned that none of these cases had been referred to the YJS in line with the guidance. Our casefile assessments found that the YJS had only been informed in 34 of the 87 CR cases that we looked at. None of the forces we inspected had an automated system for notifying the YJS, as recommended in the NPCC CR guidance.

We found multiple cases where several OoCDs were given to children without an offer of support:

| Case example |

| The victim, a boy, had been assaulted in school by a fellow male pupil. Police investigated the offence, and the boy was given a community resolution by police without referral to the YJS. This was despite the child receiving three other community resolutions for violent assaults, and having been investigated for other offences committed between 2021 and 2024, including violent offences, arson, harassment, and assaulting an emergency worker. The police had not made the YJS aware of the child or any of these incidents. |

Interventions

The NPCC CR guidance makes it clear that CRs are ‘non-statutory, the interventions agreed cannot be legally enforced or escalated to a higher disposal.’

The College of Policing APP for prosecution and case management does not contain any information about this. But the YJB CMG says that: ‘Interventions may be offered to the child; however, these are entirely voluntary and cannot be enforced if not completed.’

We were concerned to find that three of the six forces we inspected had CR forms that contained warnings about the implications of not completing the agreed actions. We found an example of one such warning signed by a child:

‘The victim/other party has intimated that he/she is willing to have this matter dealt with informally (or police believe it appropriate) and provide you with an opportunity to make recompense for your actions. This is voluntary and if you agree and complete the process plus no further evidence comes to light, you will not be subject to any further police investigation – failing to complete the agreed actions will result in legal action being taken against you.’

This practice may be misleading. It contradicted the voluntary nature of the actions and implied that legal action could be taken for failure to complete the intervention rather than prosecute for the original offence.

During our inspection, we found that five of the six forces had a CR form that the child was asked to sign, which contained an acceptance of responsibility and/or an admission of the offence, and detailed the conditions or interventions that they agreed to complete. We found that there was no consistency in the content of the forms. There was no guidance to police for what information the form should contain, or if the child should be given a copy. None of the inspected forces had systems and processes to make sure the interventions had been completed. Some police leaders we spoke to stated that, in general, taking further action against a child was very unlikely.

3.2. Acceptance of responsibility and admission of guilt (Back to top)

The NPCC CR guidance stated that these could be used in cases where there was an acceptance of responsibility or an admission of guilt.

The guidance contained an explanation of what acceptance of responsibility meant:

‘This is not defined within legislation. However, for the purposes of this guidance it is suggested that an acceptance of responsibility is different to, and should not be treated as, a PACE [Police and Criminal Evidence Act] compliant formal admission in interview. There must be evidence, written or otherwise recorded, that the suspect either accepts the facts of the case and their responsibility for them or that they accept their actions contributed to the offence.’

The NPCC guidance did not define an admission of guilt.

The College of Policing APP for prosecution and case management stated under ‘Operational considerations’: ‘Admission of guilt – the offender must accept responsibility for the offence.’

Then, further in the APP under ‘administrative considerations’:’ Confirm that the offender accepts responsibility for the offence.’

The YJB case management guidance also contained information about what was meant by an acceptance of responsibility. However, we raised concerns with the YJB about some elements of this – the risk being that children could be given a CR for something that they were either not directly responsible for, or when they would have a defence in law for their actions. We contacted the YJB about this and were pleased to see that the YJB case management guidance has been amended to be clearer about the acceptance of responsibility.

We found there was confusion between what constituted an acceptance of responsibility and an admission of guilt.

3.3. Crime outcome types (Back to top)

Crime outcome type 20

Crime outcome type 20 is defined in the HOCRR as:

‘Action undertaken by another body or agency. Further action resulting from the crime report will be undertaken by another body or agency subject to the victim (or person acting on their behalf) being made aware of the action to be taken). It is not necessary for that further action to amount to criminal processes.’

Outcome 20 should be used in cases where there had been little police investigation and no formal police action, but where the case was passed to another body or agency to progress when necessary. This was considered by the police to be a ‘no further action’.

The NPCC has not produced specific operational guidance about the use of Outcome 20, but its child gravity matrix guidance suggested it should be used for crimes that score 1 or 2 on the matrix and recommended that decisions should be made jointly with the YJS.

In the 21 cases we looked at during our inspection, there was no evidence that the NPCC child gravity matrix was used by police. During our inspection, we found that none of the OoCD decision-makers in the forces we inspected made joint decisions about crimes closed under Outcome 20.

Two forces we inspected had decided not to finalise crimes using Outcome 20 at all. The differences in the way Outcome 20 is applied make it difficult to conduct any meaningful analysis.