Effective Practice Spotlight: The Probation Service – East Midlands region

In the inspection of probation services across East Midlands, we assessed cases against HM Inspectorate of probation service delivery standards. Inspectors considered whether practice in selected cases was sufficient to meet the engagement and desistance needs of people on probation, and whether activity was sufficient to keep other people safe.

The overall service delivery ratings were calculated based on the percentage of those cases that had been identified as sufficient against each of our key questions and standards.

HM Inspectorate of Probation’s definition of effective practice is ‘where we see our standards delivered well in practice’. Effective practice was seen within a number of cases inspected as part of fieldwork in East Midlands. This spotlight is designed to highlight where practice was effective.

East Midlands effective practice summary (Back to top)

- Fieldwork took place in each East Midlands Probation Delivery Unit (PDU) between 24 February and 04 April 2025.

- We reviewed 330 cases, 216 of which were subject to a community sentence and 115 to release on licence.

- We also reviewed 149 court reports and 104 cases subject to resettlement provision.

- We inspected 22 unpaid work (UPW) cases and 27 statutory victim cases from across the region for which community sentences and licences had started between 15 July 2024 and 26 September 2024.

- The strongest practice across the majority of PDUs was found in the assessment and planning to reduce reoffending and support desistance. We also found the assessment and planning for engagement of the person on probation to be a strength in most PDUs.

- We found 91 pieces of effective practice within domain two casework.

- We found the most effective practice examples across intervention work, multi-agency working, and risk management.

In this spotlight report, we have highlighted the strongest case examples of effective practice from each PDU, across several themes related to case management.

Our standards (Back to top)

These are the HM Inspectorate of Probation standards met by the examples of effective practice selected from across East Midlands A full list of our standards, plus further reading and research, can be found on our website.

- Assessment is well informed, analytical, personalised, actively involving the person on probation.

- Planning is well informed, holistic, and personalised, actively involving the person on probation.

- Staff are enabled to deliver a high-quality, personalised, and responsive service for all people on probation.

- A comprehensive range of high-quality services is in place, supporting a tailored and responsive service for all people on probation.

- High-quality, well-focused, personalised, and coordinated services are delivered, engaging the person on probation.

Organisational arrangements and activity (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Stalking initiative, Nottinghamshire

The East Midlands stalking initiative was developed in response to a regional needs analysis, which identified that 64 per cent of Nottinghamshire’s caseload involved relationship-related criminogenic needs, with 10 per cent of convictions linked to stalking. High staff turnover and inexperience further highlighted the need for targeted support.

In collaboration with the commission and partnership team, the head of PDU supported a working group, consisting of the former deputy head of service Nottinghamshire and interested practitioners from the PDU, to develop a two-part training programme:

- Classroom-based learning on stalking models and context

- Structured consultations with a psychologist for case support.

A psychologist-led pilot programme informed the approach, which launched in March 2025 with Nottinghamshire PDU as a trailblazer, supported by De Montfort University and single points of contact in each office.

The initiative aligned with national priorities, including the February 2025 legislative change that brought controlling or coercive behaviour under automatic multi-agency public protection arrangements (MAPPA) management.1 Drawing on London’s multi-agency threat assessment model, the training aimed to build staff confidence and practical skills in managing complex stalking cases. Staff responded positively, valuing the reflective learning environment.

A formal evaluation was planned for April 2025, with future rollout dependent on funding, although there is strong local pride in the pilot programme’s success.

The case below highlights how strategic planning and multi-agency collaboration enabled effective management of a complex stalking case. Informed by psychological and specialist input, the team delivered robust risk assessment, coordinated release planning, and swift enforcement, demonstrating the value of integrated public protection efforts.

Example of effectiveness: Strategic planning in a complex stalking case

Sonny, a 44-year-old veteran with potential undiagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder, was sentenced for stalking offences and re-released on a three-day licence following previous recalls. Initially assessed as presenting a high risk of serious harm, his risk level was raised to very high after further offending, resulting in immediate recall and a new custodial sentence.

Multidisciplinary assessment support:

- The probation practitioner (PP) demonstrated a strong understanding of Sonny’s risks and manipulative behaviours, informed by input from the stalking hub psychologist and the offender personality disorder pathway.

- Effective liaison was maintained with the police, victim liaison officer (VLO), children’s social care (CSC), and prison staff throughout custody.

- CSC and police domestic abuse (DA) history were known at release, with the PP completing updated checks.

- The assessment included a thorough analysis of risk to others, identifying relevant individuals and informed by multi-agency input.

Robust pre-release planning:

- Resettlement planning included a MAPPA Level 2 meeting, approved premises (AP) referral, extensive licence conditions, and a police-led stalking protection order, all developed with input from Police and the VLO.

- These plans were discussed with Sonny pre-release, alongside referrals to wellbeing and substance misuse services, with his consent.

- Veteran support services were also integrated into the release plan.

- Risk management was reinforced through very high risk of serious harm meetings with senior probation leaders.

Outcome: The overall risk assessment and management were good, including strong multi-agency working and decision-making throughout the case which ensured that swift enforcement action could be taken to progress recall within 24 hours of re-release.

Court work (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Professional curiosity to inform pre-sentence report

Harry, a 42-year-old man, received a suspended sentence order (SSO) with a Building Better Relationships (BBR) programme and rehabilitative activity requirement (RAR) days for a DA offence. Allegations included sexual assault, strangulation, and controlling behaviour, echoing past incidents involving a previous partner.

Assessing the risk to children:

- CSC were involved with the victim’s grandchild, and the pre-sentence report (PSR) author was keen to ascertain further information regarding any risk posed by Harry.

- Liaison with CSC pursued information in relation to his ex-partner’s children and grandchildren, as well as considering the potential of harm to the children of a friend with whom he had stayed previously.

Comprehensive report:

- The pre-sentence report (PSR) provided a clear overview of Harry’s circumstances and assessed actual and potential risks.

- DA enquiries were used to inform the report, drawing upon un-convicted behaviours, including sexual assault and strangulation, despite no prior convictions.

- Prison enquiries established if there had been any further contact with the victim while on remand.

Outcome: A high-quality PSR was provided to the court, which was well-informed by DA and CSC enquiries, resulting in a good analysis of the risks posed, despite no previous convictions.

Example of effectiveness: Investigative approach to safeguarding enquiries

Liam, a 40-year-old man convicted of sexual offences with a child, was sentenced to a community order (CO) with UPW and RAR days, which included engaging in the Maps 4 Change toolkit.

Good multi-agency liaison

- The PSR author liaised with CSC from the initial court stage and completed all necessary enquiries, including with regard to children in the wider family.

- A full background of Liam’s son and a nephew was sought to establish the reasoning behind the closure of the CSC intervention.

- The PSR author also referred the case to CSC prior to sentence, recognising that circumstances had changed.

Outcome: The continued liaison with CSC continued post-sentence, including joint home visits, ensuring appropriate risk management of this case.

The ASPIRE model of case supervision (Back to top)

‘Contemporary probation practice is based upon the ASPIRE model of case supervision. In our core inspections, we judge the quality of delivery in individual cases against this model.’ 2

The four standards for inspection of adult case supervision follow the ASPIRE model by focusing on the quality of assessment, planning, implementation and review. Within each standard we assess the quality of engagement, work to address desistance and work to keep other people safe.

In the case example below, we saw evidence of effective practice across all elements of the ASPIRE model. Each example highlights effective practice in key areas such as risk assessment, trauma-informed engagement, multi-agency collaboration, and desistance-focused interventions.

Example of effectiveness: Utilising expert advice to support assessment and planning

Saad, a 47-year-old British Pakistani man, was sentenced to an SSO for the offence of stalking. There was DA within his marriage, and he continued to reside with his wife, three adult children, and teenage son, who had significant physical health needs requiring care.

Case formulation and understanding:

- The PP consulted the stalking hub early to inform assessment and stalking typology.

- A case formulation guided risk assessment, BBR suitability, and intervention planning, identifying actual and potential victims from multiple sources.

Creative contingency planning:

- The PP worked with the enforcement hub to embed the safety plan into Saad’s sentence plan, enabling breach action if not followed. This enhanced risk management within a community sentence, adding additional restrictive and preventative measures.

Focused interventions:

- Materials provided by the stalking hub were used in supervision.

- A multi-agency approach addressed Saad’s needs holistically, with referrals to Commissioned Rehabilitative Services (CRS) wellbeing services to tackle underlying issues linked to his abusive behaviour, such as self-esteem, confidence, and general anxiety.

Risk management:

- Strong information sharing with key agencies (for example, CSC, independent DA adviser, Women’s Aid, MAPPA, integrated offender management.

- Ongoing management oversight included regular case consultations between the PP and senior probation officer (SPO) due to high risk levels.

Outcome: The PP anticipated reduced support once Saad’s son turned 18 years old, and referred the case to the IOM DA cohort and MAPPA Level 2, which ensured continued multi-agency oversight, assessment, and planning.

Example of effectiveness: Effective multi-agency work to supporting desistance and safety

Clare, a 27-year-old woman, appeared in court for violent offences. She had several previous convictions, and police enquiries revealed that she was both a victim and perpetrator of DA. She had diagnosed mental health problems and neurodiversity needs.

Collaborative risk assessment:

- Clare’s neurodiversity and personal circumstances were thoughtfully considered.

- The analysis balanced risk assessment with desistance factors, highlighting Clare’s strengths and protective factors.

- All risk groups were clearly identified and analysed, with appropriate safety measures put in place for current and past victims.

Information from several sources:

- Historical records and external sources were used effectively.

- Initial information was comprehensive, spanning several years to support assessment.

- Monthly police enquiries revealed no reported incidents.

Professional curiosity:

- Upon Clare disclosing a new partner who was a registered sex offender, the PP conducted internal checks with this individual’s PP and external enquiries with CSC services regarding child contact.

- Parenting concerns raised by Clare were promptly shared and discussed with the allocated social worker.

Individualised planning activity:

- Clare’s dyslexia was acknowledged, and tailored support was provided for interventions.

- Flexibility around childcare and school schedules was accommodated.

- Planning incorporated Clare’s goals and desistance work, with collaboration from other agencies.

- Intervention sequencing, agency activities, and reporting requirements were clearly outlined.

Outcome: Clare received well-coordinated, personalised support that considered her neurodiversity, parenting responsibilities, and personal goals. CRS women’s services played a key role, offering targeted support in areas such as debt, accommodation, emotional regulation, and healthy relationships, contributing significantly to the reduction in risk of harm.

Example of effectiveness: Effective engagement and risk management

Colin, a 35-year-old man, was sentenced to a CO for sexual offences. The CO included requirements to complete UPW, a programme requirement, and RAR days. Colin had no previous convictions, but the index offending took place over a five-year period.

Involving the person on probation in the assessment:

- Colin actively participated in early assessment discussions, with attention given to his motivation to change.

- His strengths and desistance factors were clearly identified.

- His personal and work commitments were considered, with flexible appointments and clear plans for intervention delivery such as offering late night appointments and accredited programme allocation.

Planning and implementing interventions:

- UPW and RAR days began promptly.

- Colin engaged in offence-focused work through RAR sessions, with well-documented Maps 4 Change interventions replacing the delayed iHorizon programme.

Joint working with partner agencies:

- Strong collaboration with the police included a three-way meeting and two joint home visits.

- Regular information sharing supported risk management in line with ancillary orders.

- Reviews responded well to changing risks, including a referral for mental health support.

- The PP acted on safety concerns, assessing suitability for family event attendance and contact with a new baby through police liaison and family enquiries.

Outcome: This professional curiosity in risk management ensured that appropriate disclosure was made and that risk was managed effectively.

Example of effectiveness: Person-centred approach to risk assessment

Luke, a 20-year-old Black man, was convicted of assaulting an emergency worker and sentenced to a CO with RAR days. This was his first conviction. He had a history of self-reported trauma and mental health issues.

Proactive and informed engagement:

- The PP was well prepared before her first contact with Luke and reviewed all available information (for example, the PSR and psychiatric report) and identified knowledge gaps.

- There was a deliberate delay in starting interventions to build trust and rapport, with clear rationale recorded.

- The PP adjusted their approach based on Luke’s guarded presentation, exploring alternative engagement strategies.

Structured and collaborative working:

- The sentence and risk management plans were clear.

- Objectives were linked to risk, desistance, and strengths, and were accessible and discussed with Luke.

- Communication with duty officers was effective, including summaries and session goals to ensure continuity when covering appointments.

- Structured intervention delivery included toolkits with clear links to the sentence plan and rationale for each activity.

Consistent and reflective practice:

- There were detailed and reflective entries on nDelius, including initial sentence plan discussions, interventions, and review contacts.

- Home visits were conducted when Luke changed address, with thoughtful analysis of the new environment and potential risks.

Outcome: Through proactive information gathering, structured interventions, and adaptive engagement strategies, the practitioner built a trusting relationship that supported meaningful progress and comprehensive risk assessments.

Professional curiosity (Back to top)

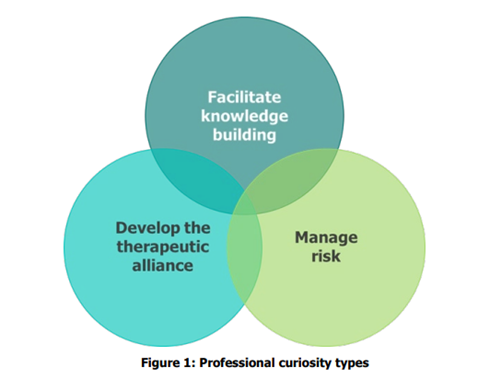

Professional curiosity is essential to effective probation practice (see Figure 1). It involves proactive questioning, critical thinking, and reflection to understand an individual’s circumstances fully. By looking beyond surface-level information and challenging assumptions, practitioners can better identify hidden risks and needs. This approach is especially important in safeguarding, where missed signs can lead to poor outcomes. HM Inspectorate of Prisons highlights that a culture of curiosity, supported by supervision, open dialogue, and awareness of bias, enhances case supervision and decision-making.

Phillips et al. (2022)3 research with probation professionals identified that practitioners’ understanding of professional curiosity fell into four broad categories:

- risk focused

- therapeutic

- knowledge building (improving the practitioner’s own knowledge)

- neutral (being generally questioning, ‘nosiness’).

While professional curiosity is often associated with assessing risk, its value extends far beyond this. Practitioners are encouraged to adopt a broader perspective, using curiosity as a therapeutic tool to build trust, explore individuals’ lives in depth, and support their own continuing professional development.

In the case example below, we saw how professional curiosity underpinned effective, person-centred probation practice. The practitioner applied critical thinking and a holistic approach to assess David’s needs, tailor interventions, and support his desistance. Through proactive engagement, targeted referrals, and a commitment to learning, the practitioner demonstrated how thoughtful, informed practice can lead to meaningful outcomes, both for individuals and those around them.

Example of effectiveness: Supporting change through informed engagement

David, a 49-year-old man, received a suspended sentence order for fraud, including RAR days, alcohol treatment, UPW, and a prohibited activity requirement, with key concerns around alcohol misuse, gambling addiction, and health issues.

Professional curiosity to inform assessment and planning:

- The PP demonstrated strong professional curiosity and built a positive working relationship with David.

- David’s needs were thoroughly assessed and informed the sentence planning.

- Together, they prioritised an alcohol intervention, recognising its link to gambling and offending.

- DA and safeguarding enquiries were completed, with no concerns identified.

- A home visit was conducted shortly after the order began.

Targeted and responsive interventions to support desistance:

- A CRS referral was made for alcohol support, and the PP familiarised themselves with the intervention, to enable meaningful follow-up.

- Recognising a knowledge gap around gambling addiction, the PP sought and received approval for specialist training, which was delivered to David which strengthened rapport and explore the impact on hidden victims, including his wife.

- The PP regularly monitored David’s attendance at Gamblers Anonymous.

- Engagement with David’s wife revealed that she had implemented financial safeguards. As a result, the PP decided not to refer to CRS finance, benefit, and debt services, tailoring support to David’s desistance needs.

Outcome: The PP supported David in developing exit strategies with Gamblers Anonymous and a local support agency and explored future voluntary work opportunities. The PP provided relevant information and signposted him to services. The training on gambling addiction enhanced awareness of the wider impact of offending, enabling the PP to signpost David’s wife to support, demonstrating a holistic approach that considered the wellbeing of those around him, despite there being no identified victim.

You can access our professional curiosity effective practice guides for managers and practitioners at our website:

Resettlement (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Embedding risk, welfare, and support in release planning

John, a 39-year-old man, was subject to two concurrent orders: an SSO for arson and a licence for a DA-related offence that pre-dated the arson. He was not heavily convicted, with his last conviction being when he was child.

Strong focus from the community offender manager (COM):

- Resettlement work within this case was particularly impressive, with the COM taking the initiative to support effective outcomes.

- The COM facilitated pre-emptive liaisons with the prison, from the remand stage right through to release.

Robust oversight of release planning:

- Release planning was initiated early, with an AP referral submitted while John was still on remand, anticipating the sentencing outcome.

- Due to late confirmation of his end-of-custody supervised licence (ECSL) and lack of AP availability before his conditional release date, the COM applied for an ECSL exception to support effective risk management.

Effective communication:

- Effective pre-release engagement was evident, including video calls and three-way contacts with the AP to support John’s transition.

- The COM maintained strong multi-agency communication, liaising regularly with CSC- and CRS-linked workers, and proactively referred John to community services such as secondary mental health care to ensure a smooth handover.

Outcome: The COM in this case ensured that a robust risk management plan was in place in preparation for release, which John fully understood. Post-release, the COM maintained momentum throughout delivery and reviewing, demonstrating a considerate approach which was balanced with welfare, risk, and need.

Example of effectiveness: Coordinated practice in a recall and re-release

Brian, a 31-year-old man with a traveller heritage, received a short prison sentence for the offence of affray. During this sentence, he was released and recalled and was re-released into the community at the time of inspection.

Brian spent just a few days on post-sentence supervision licence before suspension under ‘Probation Reset’.4

Proactive partnership working:

- The PP completed extensive pre-release work within just one month of allocation.

- The PP engaged with partner agencies, family members, and NACRO (National Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders), and arranged two video-link sessions.

- The PP worked the case vigorously, completing police and safeguarding enquiries and subsequently making a CSC referral.

- Managing this case was complex due to Brian’s extended family and contact with multiple children. The PP worked closely with CSC to identify and assess risks to all children involved.

Clear communication and risk-led release planning:

- A handover from the prison offender manager (POM) to the COM took place, and Brian was offered remote contact.

- His proposed address was checked and multiple other options were considered, both of which were unsuccessful because of his risks

- The PP was also clear in her communication with Brian around Probation Reset at the started these discussions at the earliest stage.

Outcome: Brian was difficult to engage, and the PP acknowledged that the timeframe available pre-release was not sufficient when working with a challenging person on probation. However, the PP made all efforts to engage him and enable support services to be in place for him on release.

Public protection work (Back to top)

Public protection is a core function of probation services and is central to their purpose. It involves identifying, assessing, and managing the risk that individuals on probation may pose to others, particularly where there is a risk of serious harm. According to HM Inspectorate of Probation guidance,

‘Defensible decision-making at every level, from practitioner to senior leadership, supported by evidence-based practice, validated assessment tools, and effective supervision skills’. 5

This can be achieved by:

- conducting thorough risk assessments

- developing and implementing robust risk management plans

- coordinating with other agencies (for example, police, CSC, mental health teams) to share information and manage risk collaboratively.

Public protection is vital because:

- It helps prevent further harm to victims and the wider public.

- It ensures that probation services fulfil their statutory duty to protect the public.

- It builds public confidence in the criminal justice system.

- It supports effective rehabilitation, as managing risk is often closely linked to addressing the underlying causes of offending.

Our inspection standards emphasise that high-quality public protection work requires clear communication, timely information sharing, and multi-agency collaboration.6

In the case examples below, we observed where probation practitioners met our public protection standards through robust risk management, inter-agency collaboration, and targeted interventions. In both cases, practitioners demonstrated a clear focus on managing risk of harm, protecting victims, and supporting desistance.

Example of effectiveness: Licence conditions and multi-agency collaboration

Tom, a 33-year-old man, was sentenced to custody for violent offences, criminal damage, and assaulting an emergency worker. The most serious offences occurred in a DA context, with children present. He had 11 prior convictions, including domestic assaults, and his offending was worsened by alcohol misuse.

Targeted conditions to reduce risk and support desistance:

- Effective resettlement work was evident, with strong engagement between the PP and Tom.

- Robust planning led to appropriate licence conditions, including alcohol monitoring, DA electronic monitoring, and no-contact restrictions, to protect others.

- Tom understood the licence conditions, and an AP placement was found, and secured in time for release.

- Assessment and planning activity in relation to desistance and the safety of others was positive.

- There was good evidence of inter-agency working, and MAPPA Level 1 reviews were completed in conjunction with MOSOVO (management of sexual or violent offenders) staff and an SPO, to ensure that the correct level of risk management was applied.

- DA enquiries were also completed regularly, and informed decisions related to licence requirements.

Outcome: The safety of others was a key priority in this case, with the external controls placed on Tom and actions taken by the PP having a focus on risk. Tom was placed in an AP post-release, and trail monitoring tag and alcohol tags were routinely monitored.

Example of effectiveness: Information gathering from partnership agencies to inform risk

Will, a 32-year-old man of White, gypsy, Irish traveller heritage, a first-time offender, was sentenced without a PSR for DA-related offences, misuse of electronic communications, criminal damage, and harassment. He received a CO with RAR days, UPW, and a restraining order to protect the victims.

Tenacious information sharing with agencies:

- Post-sentence DA enquiries revealed a pattern of entrenched abuse across multiple ex-partners and child safeguarding concerns involving alleged abuse.

- Despite Will’s poor compliance, the PP showed persistence, engaging agencies, overcoming information-sharing barriers, and swiftly referring concerns about the victim’s unborn child.

Thorough risk management planning:

- The risk management plan was thorough, outlining restraining order controls, behavioural monitoring, compliance checks, and appropriate disclosures.

- Risk planning matched the case’s complexity, incorporating targeted interventions, such as the Skills for Relationships Toolkit and Stepwise Programme.

- Desistance planning addressed the key areas of accommodation, substance misuse, and thinking patterns, with clear links to partner agency support.

- The contingency plan was detailed and personalised, covering all identified risks and assigning clear responsibilities.

Outcome: Will was breached on the CO and resentenced to custody. The PP’s robust risk management plan enabled swift enforcement, with well-evidenced risk factors supporting the court’s decision for a stronger sentence.

Interventions (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Supporting safe reintegration through specialist intervention and planning

Gemma, a 34-year-old woman, was sentenced to 20 months’ custody for sexual offences against a child.

Specialist intervention and bespoke offer:

- Resettlement was well managed, with a thorough POM/COM handover enabling effective release planning.

- Strong in-reach work helped build rapport with Gemma, with the PP showing empathy and support for her vulnerability.

- Efforts to reduce isolation included enrichment activities that boosted Gemma’s confidence, self-esteem, and emotional regulation.

- Gemma engaged with the offender personality disorder (OPD) team through intensive intervention and risk management services (IIRMS) and accessed mental health support.

- The PP prepared Gemma for release by discussing licence conditions and accommodation.

- IIRMS provided tailored support via the Options for Change programme, flexibly adapting their criteria to meet Gemma’s needs despite her medium risk level.

Outcome: As a result of the appropriate level of contact and appointments offered, together with support and delivery of interventions addressing risk and need, Gemma’s engagement and input were positive, both pre-release and when she was released into the community.

Example of effectiveness: A trauma-informed approach to effective work with a complex young adult

George, a 19-year-old Black British man of African heritage, received a custodial sentence for drug offences. He had prior involvement with the youth justice service for violent offences and robberies, with known gang affiliation, weapon carrying, and a previous National Referral Mechanism (NRM) decision following concerns of exploitation.

Effective assessment and trauma informed practice:

- A comprehensive assessment addressed George’s vulnerabilities, risk factors, and the basis for the NRM decision.

- His lived experience, including trauma associated with gang affiliations, time in local authority care, and periods of custody, were explored.

- The PP demonstrated a strong trauma-informed approach, considering George’s maturity and background, which informed decision-making.

- OPD team consultations informed intervention planning, offering strategies to build trust and support emotional development.

- The PP applied these techniques effectively, highlighting the value of OPD team input in managing a complex young man.

Outcome: The case was well managed through custody and release. Despite differing views across the professional network, the PP secured a psychologically informed planned environment AP placement with an extended stay, supporting risk management, professional engagement, and a structured transition into the community.

Example of effectiveness: Supervision and desistance work

Steven, a 63-year-old man, received a Suspended Sentence Order for sexual offences against children, including requirements to complete the Horizon programme, RAR days, and Unpaid Work. He lived with his wife and adult son, was assessed as Medium Risk of Serious Harm, placed on the Sex Offender Register, and made subject to a Sexual Harm Prevention Order. Frequent changes in supervising officers delayed offence-focused work, and Steven consistently resisted engaging in discussions about his sexually harmful behaviour.

Multi-agency collaboration

- There was robust liaison with the MOSOVO (Management of Sexual Offenders and Violent Offenders) officer, particularly regarding Steven’s employment prospects and internet access.

- Risk was effectively managed through regular information sharing between agencies, ensuring that Steven’s job applications and roles were scrutinised to prevent heightened risk to others.

Desistance and protective factors

- Work was undertaken to build Steven’s protective factors and personal strengths. This proactive approach contributed to a more holistic view of him beyond his offending history.

- A notable intervention focused on Steven’s tensions with his neighbours. The PP responded with empathy, making themselves accessible and responsive to Steven’s frequent communications.

- The PP liaised with the council and contacted the Anti-Social Behaviour (ASB) team, sharing relevant details including police reports.

Outcome: The multi-agency effort led to a Community Protection Notice (CPN) being issued to the neighbours, which significantly improved Steven’s emotional stability and session engagement. This was especially meaningful given that he had previously attributed aspects of his offending to feelings of boredom, loneliness, and social isolation. The resolution of the neighbour conflict contributed to the reduction in crisis management and a more stable presentation during supervision.

Statutory victim work (Back to top)

Example of effectiveness: Effective communication and information exchange to support disclosure decisions

The victim, who had significant mental health needs, was subjected to an intentional strangulation offence. The perpetrator received a custodial sentence.

Throughout the sentence and release planning, the VLO worked closely with the PP, prison staff, police mental health teams, and the MAPPA coordinator, to prioritise the victim’s safety and wellbeing. Sensitive information, such as the release date, was shared only when the victim’s mental health worker was available to provide immediate support.

Recognising the victim’s heightened vulnerability, the VLO carefully considered what information was necessary to share, and when. For example, when the perpetrator was briefly hospitalised under constant supervision, the VLO decided not to disclose this, to avoid unnecessary distress, given the victim’s history of self-harm.

The victim, previously in an intimate relationship with the perpetrator, had relocated. While an exclusion zone (EZ) was initially requested, police advised that this could risk revealing the victim’s new location. The VLO supported the victim in deciding against the EZ and instead arranged for a DA marker to be placed on the new address.

When the perpetrator was recalled and became unlawfully at large (UAL), there was recognition that, given the time of the incident, this individual could be UAL for an extended period and as there was no EZ, the victim and the perpetrator could potentially come into contact. The VLO coordinated with internal and external partners to ensure that the victim was informed, balancing the risk of contact with the victim’s right to know.

The VLO maintained regular contact with an SPO, receiving guidance that supported well-informed, balanced decisions, ensuring that the victim’s safety, mental health, and statutory rights were upheld throughout.

Example of effectiveness: Challenging police on decision to pursue victim contact

The victim, a woman targeted in a serious arson attack in 2006, had petrol poured through her letterbox and set alight. A smoke alarm alerted her, allowing her to extinguish the fire, although occupants needed treatment for smoke inhalation. The perpetrator, holding a grudge over a personal belief involving his ex-partner, received an imprisonment for public protection (IPP) sentence for arson with intent to endanger life.

Although the victim had brief contact with the victim contact scheme in 2013, she had disengaged by 2016. The last known correspondence, in 2017, was returned marked ‘addressee gone away’.

In 2020, a MAPPA chair asked the police to trace the victim’s whereabouts, to re-establish contact. However, the victim liaison senior probation officer (VLSPO) appropriately challenged this action, highlighting the intrusive nature of the request, given the time elapsed and the victim’s clear wish not to engage. The VLSPO’s response demonstrated strong victim-centred practice, balancing professional curiosity with respect for the victim’s autonomy. As a result, the MAPPA chair revoked the action, recognising the importance of upholding the victim’s choice.

Example of effectiveness: Victim support and information sharing

This case involved two male perpetrators, one of whom was an adult and the other only 14 at the time of the offence.

The victim relocated to London after the offence and opted into the victim contact scheme. The VLO built a strong relationship with this individual, offering personalised support that considered her vulnerabilities and need for consistency.

Although contact was briefly lost before the perpetrators’ release, it was re-established when the victim returned to the area. The VLO shared pre-release information, ensured that the victim’s views were considered by PPs managing both perpetrators, and arranged a joint visit with the victim to address her concerns.

When the VLO was not invited to a MAPPA meeting, they appropriately challenged this oversight. Follow-up actions were taken, and the victim was kept informed. Licence conditions, including no-contact restrictions, were clearly explained.

The VLO supported the victim from 2018 until the case was made dormant in 2023, demonstrating sustained and trauma-informed engagement throughout.

Management oversight (Back to top)

Management oversight is a term used in the Probation Service to encompass the oversight of casework, staff wellbeing, and countersigning. During the thematic inspection, ‘The role of the senior probation officer and management oversight in the Probation Service’, and for the purpose of this spotlight report, management oversight is defined as follows:

‘ …the formal process by which a manager, most often an SPO, [senior probation officer] assures themselves that operational delivery is undertaken consistently and to the required standard. This is in line with the definition used by His Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS). Management oversight may include formal and informal meetings between the SPO and the probation practitioner (PP). Similarly, countersigning activities, such as those for the offender assessment system (OASys), are part of the management oversight framework.’

Below, we share examples of where we saw effective management oversight of cases, highlighting the critical role this plays in ensuring high-quality and responsive probation practice. Whether through proactive case allocation, escalation of risk, or collaborative decision-making, these examples demonstrate how effective oversight supports practitioners in managing complex cases, safeguarding individuals, and delivering interventions that are both proportionate and person centred.

Example of effectiveness: Management oversight support in case allocation and decision making

Brenda, a 33-year-old woman, received a CO following a breach of a previous CO for violent behaviour towards her partner and strangers. Her offending was linked to recent experiences of sexual exploitation, which triggered emotional wellbeing issues and late-onset offending. This was recognised early, and planning reflected a trauma-informed approach.

Initial allocation notes from the SPO provided valuable insight into Brenda’s needs and guided case management. The PP used this to shape a responsive assessment, exploring barriers to engagement, such as substance misuse, poor mental health, low motivation, and patterns of false compliance.

Although Brenda’s engagement was inconsistent, meaningful support was delivered through the Women’s Work programme when she did engage. Management support helped to ensure a trauma-informed response to her attendance issues.

When Brenda reconnected with her sister and moved in with her, the PP identified this as a stabilising factor. Risk discussions with the SPO supported this decision, with contingencies considered and a review of the OASys and risk management plan undertaken.

Example of effectiveness: Effective case allocation with clear practice guidance

Jack, a 27-year-old transgender man who identified as bisexual, received an SSO for offences involving indecent images of children. His behaviour was linked to a pornography addiction that escalated during the Covid-19 pandemic, with evidence of sexual preoccupation and interest in both male and female children.

The case allocation was thorough and proactive, identifying key areas not addressed in the PSR and providing clear, trauma-informed guidance to support effective case management.

The SPO demonstrated diligence and sensitivity during case allocation. She supported the allocated PP by flagging that Crown Prosecution Service documentation was difficult to interpret and contained explicit content, advising a debrief with a trusted colleague or SPO. She also identified references to potential non-convicted offending and directed the PP to consult with MOSOVO during the initial assessment.

Safeguarding concerns were clearly outlined. The SPO emphasised the need to consider Jack’s younger siblings as potential victims and to refer to CSC. Adult safeguarding concerns were also noted in regard to Jack’s mother’s health. Jack had disclosed childhood sexual abuse and exposure to DA, and was socially isolated, factors that the SPO highlighted as relevant to risk and engagement.

The SPO recommended early actions, including a home visit, referral to LGBT+ support services within five weeks, and commencement of the Maps 4 Change programme. A referral to the personal wellbeing service for counselling was also advised.

Example of effectiveness: Effective risk escalation and oversight

Jack, a 32-year-old man, was sentenced to a CO with RAR days for DA offences, without a PSR. The sentence did not reflect the complexity or risk level of the case.

Following sentence, Jack’s risk was reassessed and raised to high risk of serious harm to intimate partners. Early management oversight ensured appropriate case allocation, with the SPO and PP jointly reviewing and confirming the risk level.

They also agreed to request three years of DA history, which revealed a pattern of prior abuse that would have otherwise gone unnoticed.

This collaborative approach between the SPO and PP strengthened assessment and planning, ensuring the case was managed in line with the actual level of risk.

References and acknowledgements (Back to top)

This Effective Practice Spotlight is based on information sourced while undertaking our inspection of the Probation Service – East Midlands region. The manager responsible for this inspection programme is Dave Argument. Helen Amor, effective practice lead, has drawn out examples of effective practice from the inspection of the region. These are presented in this guide to support the continuous development of these areas in the probation region. We would like to thank all those who participated in any way during the inspection, and especially those who have contributed to this guide. Without their help and cooperation, the inspection and Effective Practice Spotlight would not have been possible.

- UK Government. (2025). Better Protection for Victims from Domestic Abusers. [Press release] 03 February. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/better-protection-for-victims-from-domestic-abusers (Accessed: 09 June 2025). ↩︎

- Supervision of service users – HM Inspectorate of Probation (n.d) ↩︎

- Jake Phillips, Sam Ainslie, Andrew Fowler, Chalen Westaby. (2022). “What Does Professional Curiosity Mean to You?”: An Exploration of Professional Curiosity in Probation’. British Journal of Social Work, 52 (1), pp. 554–572 ↩︎

- Probation Reset: A strategic policy initiative introduced within the UK Probation Service to reduce workload pressures by refocusing practitioner efforts on high-impact areas, such as early-stage sentence management and high-risk individuals. It involves scaling back routine contact in the final third of supervision periods unless specific risk criteria are met. HMPPS Rehabilitation Strategy ↩︎

- HM Inspectorate of Probation (2021). Multi-agency public protection arrangements. ↩︎

- HM Inspectorate of Probation (2024). Standards for inspecting probation services. ↩︎